In August last year, some 300 unsuspecting car buyers from across India trooped into a hotel in Noida. Each one had a personal favourite, but was indecisive on which model to drive home. What they were not aware of was that their collective preference would govern a global carmaker’s road map in India. It was fairly straightforward and standard market research fare. The individual would enter a room where three cars were parked. All the models would be covered and potential customers would stand four metres from each car. As the research staff questioned their expectations from a car, the identity of the three brands would gradually be revealed – Maruti Alto 800, Hyundai Eon and Datsun redi-GO.

Guillaume Sicard, president, Nissan India, which manufactures the redi-GO, finds it hard to conceal his incredulity as he recalls the event, “They loved the redi-Go for its chrome grill, tall-boy looks and its spacious interior. But eventually switched loyalties to the Alto even after calling it old-fashioned,” he adds, perplexed. What swung the deal in favour of the Alto was the easy availability of spare parts or the recommendation of a friend, who vouched for the Alto or just any car by Maruti. “What I found fascinating was how although people preferred one car, they decided in favour of another,” reveals Sicard. Like many, an experience during his two-year stint in India, this was another instance of the unexpected taking place.

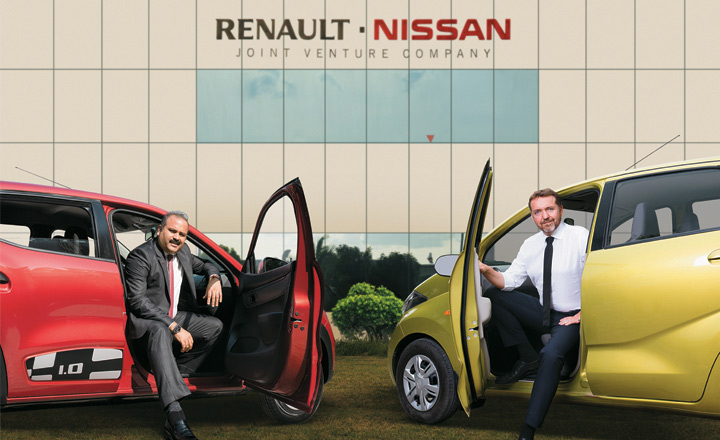

redi-GO, the entry-level hatchback, launched this summer, has sold 7,500 units so far. That is a far more impressive record than that of the earlier products rolled out by Datsun in India. This, coupled with the success of the Renault Kwid – both manufactured from a sprawling 480,000 capacity factory in Oragadam, some 45 km from Chennai – has put the spotlight back on Renault-Nissan Automotive India. As part of a global alliance, the two carmakers have a common research and development pool, in addition to shared production processes. However, once their models are rolled out of the factory, they compete ruthlessly.

For both Renault and Nissan, there has been a visible shift from manufacturing large cars to focusing on the entry-level segment, which accounts for a handy 25% of the total volume in India. In fact, as much as 70% of cars sold in the country are priced below Rs.7 lakh. And both the automakers are steering ahead to occupy a bigger share of this pie. The redi-GO was launched at Rs.2.39 lakh, making it India’s cheapest car; while the Kwid, that hit the roads in September 2015, has made impressive in-roads in the Indian market with over 75,000 units sold so far, adding up to a 4.5% market share. Competition is feisty and primarily led by Maruti Suzuki. This year, the Renault-Nissan combine became the third largest by volume, edging past Mahindra and Mahindra. The real battle has only begun now, as it comes up against Maruti and its large portfolio.

For both Renault and Nissan, there has been a visible shift from manufacturing large cars to focusing on the entry-level segment, which accounts for a handy 25% of the total volume in India. In fact, as much as 70% of cars sold in the country are priced below Rs.7 lakh. And both the automakers are steering ahead to occupy a bigger share of this pie. The redi-GO was launched at Rs.2.39 lakh, making it India’s cheapest car; while the Kwid, that hit the roads in September 2015, has made impressive in-roads in the Indian market with over 75,000 units sold so far, adding up to a 4.5% market share. Competition is feisty and primarily led by Maruti Suzuki. This year, the Renault-Nissan combine became the third largest by volume, edging past Mahindra and Mahindra. The real battle has only begun now, as it comes up against Maruti and its large portfolio.

Uneasy start

Prior to the Kwid, the only successful model from the global combine was Renault’s Duster. The SUV was launched in mid-2012, a year after Renault-Nissan entered India. The first set of cars including Scala, Fluence and Koleos from Renault and Sunny and Micra from Nissan failed to take off. Finally, the Duster came and conquered some market share. The French carmakers created a brand new segment with the Duster called the compact SUV. It was a humble, yet stylish mix between a sedan and an SUV, priced perfectly for an aspiring Indian audience.

Initially, the Renault-Nissan alliance adopted a cross-badging strategy (rolling out the same products under two brands with basic cosmetic changes). The Nissan Sunny preceded the Scala and the Terrano followed the Duster. But in 2014, this approach was altered. Cross-badging has its advantages, with cost-efficiency being the most important one. Sicard admits that the Japanese car-maker would not have been able to launch an SUV like Terrano without badge-sharing. “The intent was to optimise the arrangement, where we could have the same car from the inside but with a totally different make-up. It could be criticised from a marketing point of view but it was a good idea since we had just entered India,” he says in defense of cross-badging, while agreeing, “As we get stronger, it might not necessarily be the best solution today.”

Part of the reason behind abandoning the approach also resulted from the Indian customer’s refusal to pay a premium for just cosmetic changes. It’s not just a matter of need but final purchasing decisions are made on the basis of what really works. Even though Duster was a roaring hit, the Nissan Terrano, a more stylish and premium-priced twin of its French counterpart didn’t find many suitors. Cross-badging meant that Nissan had to price the Terrano at a premium to prevent cannibalising Duster’s sales. And buyers simply gave the Japanese car-maker’s model the thumbs down.

Duster’s glory didn’t last too long either. Soon it came under serious attack from newer entrants such as the Ford EcoSport, Maruti Suzuki’s Vitara Brezza and the Hyundai Creta. Consequently, Duster’s monthly sales dropped sharply from a peak of 4,000 units to around 1,600 units; the Hyundai Creta does close to 8,000 units, while the Vitara Brezza sells over 10,000 units. The success of its rivals has been attributed to a combination of factors – aggressive pricing and a significant excise benefit for vehicles in the sub-four metre segment. With the arbitrage between diesel and petrol prices non-existent, buyers have shifted to petrol versions, which are usually cheaper. With no petrol version on offer, the Duster has lost out on attracting more buyers. Sumit Sawhney, CEO, Renault India, admits that the Duster, today, with a length of over four metres operates in a very small segment. “We did not have a strong dealer network in tier 2 and tier 3 and were restricted to tier 1. That will be addressed now as we take the Kwid to smaller centres, where the Duster can also be sold,” he says. While he does not go beyond saying, “we are evaluating various options”, the dealers hint at a smaller version of the Duster being on the anvil.

Brand new strategy

While cross-badging did not work, Nissan’s decision to develop Datsun, a brand that it owned, for smaller car models for different markets also came a cropper. This was evident in both the Datsun GO that was launched in India in mid-2014 and the GO Plus, which was unveiled a year later. Apart from India, they were launched in Indonesia, Russia and South Africa. Both the models failed to garner any interest and Sicard attributes that to various factors. The GO, for instance, he says, did not focus on value and also suffered due to poor communication. The advertisement featured a 40-year-old father with his two kids, which Sicard says was not aspirational. “We should have had a 25-year-old instead,” he says. Quality, too, was an issue. According to Roshun Povaiah, super moderator, Zig Wheels Forum, the plastic used in the interiors of the automobile was “tacky”. “It had non-retractable seat belts apart from just one wiper. These were obvious indications of cost-cutting. There was nothing by way of value,” he adds. Even the GO Plus, while being a seven-seater multi-purpose vehicle, was “just a longer version but still tacky.”

The more fundamental question is if Nissan should persist with a not-so-well known budget brand in the highly competitive small car market. The Japanese major has positioned Datsun as a budget brand globally and not getting it right with Go and Go Plus, has put Datsun on the back foot in India. But Sicard strongly defends the strategy. He argues that India is a dual market and will continue to be so in the future. “In this context, it would be a stretch for one brand to cover such a large spectrum. Therefore, it’s necessary to develop two brands, each with its clear positioning,” emphasises Sicard. Hormazd Sorabjee, editor, Autocar India agrees. “Competing with multiple brands is a good strategy, which is what Maruti is also doing with Nexa, but it takes both time and money,” he adds.

The lessons learnt from the earlier failed launch are now evident in the Kwid and redi-GO. There has been a marked change in the approach to make them feature-rich and promote them with a peppy communication campaign. “It was critical to understand that the customer here would closely look at things like the quality of plastic and interiors, and features like power windows, using a remote key to open the car etc.,” says Sicard. “You can’t have the mindset of developing a cheap car for a developing country. If the only priority is to develop a car for Rs.3 lakh, you will be in trouble. Buyers here want all the elements of comfort and style,” he points out.

That explains why the Renault-Nissan alliance adopted the Common Module Family (CMF) structure. It’s a platform, jointly developed by Renault and Nissan, which allows building a wide range of vehicles from a smaller pool of parts. The idea is to save on costs and deliver better value for customers. The Kwid is the first vehicle built on the CMF-A (entry level or A-segment cars) architecture with the redi-GO following thereafter. The CMF-A platform was built with high localisation – Kwid and redi-Go have 98% localised components, thereby driving down overall costs. Sicard estimates that the car would have been “at least 20% more expensive otherwise.”

Under the CMF-A platform, the components have been developed from scratch, along with 400-odd local partners. Abhishek Jain, executive director of the Noida-based PPAP Automotive, a company that manufactures the inner and outer belts, says, “We used nothing from our existing work. For the inner and outer belt, we reduced the height and width by 1-2 mm. That reduced the overall weight of the component by 10% and reduced material consumption also by 10%. In the past, we have suggested this to other manufacturers as well. They always said we would like to go with international standards and our suggestions never went through. In the case of Renault-Nissan, they liked the idea and it was implemented.”

Vendors were roped in at a very early stage. Vineet Sahni, CEO of the Rs.1,300-crore Lumax Industries, the vendor for gear knobs, license lamps, bumper protectors and the front bumper liner, says, “Since we got involved early on, we got the time to get things right and eliminate wastage. Decision making was very quick and it was clear that low-cost manufacturing was always the focus,” he says. Those cost savings were not to beef up the bottomline, but to add more features to the cars. For instance, the Kwid offers an all-digital instrument cluster, a responsive touch screen, bluetooth telephony and a gear shift indicator at the top end. Why all this for a small car? The logic is to draw the customer into the showroom through attractive pricing but ensure that he opts for a more expensive model. For the redi-Go, the top-end contribution is 35% while it is around 55% for the Kwid. Dealers say a sedan is being planned for the Indian market based on the CMF-A architecture.

In terms of its communication, there is a clear focus on the youth. If redi-GO’s campaign speaks of the car as being for the “ready-to-go generation”, the Kwid has Bollywood heart-throb Ranbir Kapoor as its brand ambassador. According to Sawhney, a young face was critical for the young brand. “It had to be aspirational, so we decided to bring in the movie star,” he says. While the impact of using a celebrity can never be assessed accurately, so far the sales numbers have been great. Sorabjee says that both the redi-GO and Kwid are fundamentally good products and cost-competitive. “They have learnt from their mistakes. Today, Maruti Alto should be very worried because of the presence of credible alternatives in the market,” he avers.

Head to head

For Renault-Nissan though, the fight for customers will be anything but easy given the seamless trust Maruti has built over the years. Maruti’s advantage begins with its first-mover status and extends far beyond that. From the time it entered the market in 1984 as a joint venture with Japan’s Suzuki, the company has been prolific in rolling out a series of models to appeal to the Indian buyer. While its focus on fuel economy, reliability, dealer reach and affordable spares has ensured a sticky customer base, the large portfolio of cars and swelling customer base made dealers latch on to the Indian car-maker, thus, perpetuating its growth.

It’s been tactful at targeting the right customers too. Jagdish Khattar, Maruti’s former managing director, narrates a story that goes back to 2000, when he learnt from a dealer in Varanasi that a school teacher had bought a Maruti 800. In almost no time, two more teachers in the same school followed suit. “It was obvious there was a market and we quickly joined hands with SBI to finance the purchase. That teacher’s scheme alone sold 15,000 cars,” he says.

Khattar points out that the average salary for a school teacher back then was around Rs.18,000 per month. “At that point of time, the cost of a car was computed as one year’s salary. Based on that, a customer could easily buy a Maruti 800 and as the salary slabs increased, our larger portfolio helped in getting more customers,” he explains. This continuous process of adding more buyers meant simultaneously reaching out to a newer audience. A similar scheme for court judges and lawyers did exceptionally well, recalls Khattar.

That keen insight on consumer behaviour would not have worked beyond a point unless Maruti delivered products for a wide audience. The automaker’s large and relevant portfolio meant that customers almost always got what they wanted, with or without the company’s targeted schemes. “Just in the Rs.2 lakh–5 lakh price bracket, we had the 800, Wagon R, Alto and Zen. The buyer could pick any one based on his budget,” boasts Khattar.

According to Abraham Koshy, marketing professor at IIM-Ahmedabad, for a buyer, Maruti was a car that was affordable, comfortable and reliable. “That was a lethal combination and bad news for competition then. It came to be known as a small car only after bigger cars came in,” he says. The car, by itself, forms just one part of the story. Ensuring that the car is available requires creating a huge dealer network. Maruti today, boasts of a formidable network of over 1,800 dealers. By contrast, Hyundai has over 450 outlets, while Renault and Nissan have 220 and 232 respectively. The importance of having a large dealer network cannot be ignored and both Sicard and Sawhney admit that there is a lot of work to be done. Renault will have another 50 outlets by this December and Nissan, too, is expected to unfurl an equal number by March 2017. Still, that number will be way behind Maruti.

It’s not just the number of outlets, actually. The power of Maruti’s dealership is derived from the compelling proposition it has created with dealer viability being the core focus area. This is important because a dealer makes barely 3-4% each time he sells a car. With that kind of margin, he has to depend on other sources of income. A well-run dealer outlet can derive as much as 80% of its turnover from servicing cars. And when a company has a bouquet of cars on sale, there is more money to be made from areas such as insurance and financing. “The profitability of a dealer increases dramatically when all this takes place. It would have been difficult with a smaller range of cars,” reminds Khattar.

That’s also the rationale behind developing True Value, the carmaker’s used car vertical. “The foundation of Maruti really comes from the over 1,000 True Value outlets, where at least 25,000 cars are exchanged every month. The idea is to create multiple revenue streams for a dealer,” he explains. In the case of True Value and the more recent Nexa outlets for high-end cars which have now reached 150 outlets, existing dealers get priority. As a result, the dealer becomes a comprehensive business partner and for the company, it increases the number of touch points. Sanjeev Bafna, who was among the first lot of dealers appointed by Maruti in 1984, has an outlet each in Nashik and Nagpur, with a similar spread for Nexa. “The good thing about Maruti’s brands is that there is a continuous flow of first-time buyers and those looking to exchange their cars for another Maruti brand. This has ensured that growth each year has been at least 15-20%,” he says.

In the year 2000, Maruti introduced an interesting element in dealer initiatives when it entered the motor-driving school segment. Set up in association with the dealers, there are 360 of them today. “At least 10% of those who get a licence end up buying one of the Maruti cars,” smiles Khattar. Interestingly, half the candidates enrolled at these training centres are women drivers. “That’s because we hired lady instructors as a part of our strategy.” Women form a huge market and familiarity with the car and its reliability is a far more important consideration for women than men.

Covering the distance

While Renault and Nissan will take some time to build their distribution presence, Renault has forged ahead at an unprecedented pace so far. “No one in India has so far opened 220 outlets in the first four years of operation,” says Sawhney. Expanding the network is tricky though. “It is a chicken and egg situation. You can always engage with the dealer community but ultimately the cars need to sell well to retain their attention,” says Sawhney. He admits how that is a huge mountain to climb, “Dealership is not an easy business because it is capital-intensive and calls for a lot of commitment. We have to identify people who will be with us for the long haul.”

That explains Renault’s differentiated dealer strategy. A city like Pune will have a 6,500 square feet showroom displaying its half a dozen cars, in addition to a body shop. On the other hand, a smaller centre like Baramati will adopt an asset-light model with just a couple of cars in a 2,500 square feet outlet, a compact workshop and no body shop. Workshop on Wheels, a fully-equipped mobile workshop, launched by the French auto maker a couple of months ago, will travel to locations with smaller outlets that don’t have a workshop facility. The focus on smaller centres is clear given that, of the 65 outlets that opened this year, at least 70% came up in these areas.

Dealers have been given larger territories to work with too. Hemang Parikh, who owns Renault Nagpur, for example, has two large outlets in the city. Over time, he has opened showrooms in not just neighbouring locations like Yavatmal, but also in cities such as Aurangabad, Pune and Nashik. In all, Parikh runs 13 Renault outlets today, of which three are asset-light in Chandrapur, Akola and Baramati. It is estimated that while the 220 Renault outlets are owned by around 70 dealers, for Maruti’s 1,800 outlets, the corresponding figure is a good 1,000. “Apart from giving us a greater geographical spread, we get better economies of scale. While there is greater accountability, there is a huge incentive too, to do well in an arrangement like this,” says Parikh.

Nissan is working on a different strategy while retaining its focus on smaller areas. Its network is divided into 232 outlets that house both Nissan and Datsun models with 60 dedicated showrooms for Datsun. For 160 smaller towns, there are an equal number of rural dealer sales executives, who work with the closest dealers and assist customers. “These executives will not be in centres covered by Nissan dealer outlets but in adjoining locations,” reveals Sicard. This is in addition to its mobile workshops called Datsun Mobile Service Assistance for smaller centres, where there are 30 mobile workshops covering 100 centres. With an intention to launch more service points, the Japanese automaker announced a strategic partnership in June this year called MyTVS, a company owned by TVS Automobile Solutions. “When you are small, you have to be clever and look for ways to increase coverage,” he asserts. The eventual plan for tier 2 and 3 centres is to have exclusive Datsun outlets.

New Model Rollout

While distribution is being beefed up by both the global automobile majors, the core product still continues to be at the centre of their strategy. The Kwid has launched its one-litre version at Rs.3.82 lakh, pitching it directly against the Eon and WagonR. Sawhney is clear that there will be a new product every year. “The CMF-A platform is versatile and can offer many body styles. Obviously, we will look at options within the sub-four metre segment although we can go beyond that as well,” he says.

However, the challenge lies in making every model more compelling than its competitor and achieving versatility is easier said than done. Sicard says that in markets like the US, Europe and Japan, it is possible to have 20 cars since they can be imported. “In India, we have to invest no less than $200 million per car and that means we need to be really sure about what we launch,” he says bluntly. The plan is to have about three cars each for Nissan and Datsun. “I am not very fond of a large product portfolio. For example, Hyundai does pretty well with a not-so-large portfolio and that is the strategy we would like to follow,” he says.

With stiff competition, there is a constant need to offer something new to sustain the pace of growth. And that growth figure was driven entirely by new car sales last fiscal. “If you remove these new models, the growth rate of the market was down by 10%. The Indian customer, therefore, is looking for something new all the time,” declares Sicard. That is only partly true because successful cars like the Indica and Innova have sold well for years without any modification. Those examples are quite few though.

Not wanting to be left out, Maruti introduced a revised version of the Alto early this year after the launch of the Kwid and before the Datsun redi-GO. This was a basic facelift with small changes in the grill, bumpers and power steering for the top-end. But now it’s working towards a tall boy version of the Alto, which could hit the roads in 2018. The tall boy is not a challenge for Maruti since it already has the experience of developing WagonR and Ritz. Even South Korean automotive manufacturer, Hyundai, has a product line that is running full this year, which includes a facelift for the i10 and a new version of the Tucson SUV. A small car is said to be in the works and that will be a global launch, out of Korea in all probability. Rakesh Srivastava, senior vice-president, marketing and sales, Hyundai Motor India, reveals very little when he says that there is a product plan for the Eon.

Speaking of product launches, the Renault Kwid marks the beginning of a new playing field in the small car segment. And much of that success is driven by the recognition that the small car has features that go beyond an automobile’s basic functionality. “Kwid got it right not just on parameters like fuel efficiency but also with looks and features,” says Koshy. “On the contrary, the redi-GO is not a highly differentiated product and will take on the Alto on price, while the Kwid is up against the Eon and WagonR. This will ensure both brands grow independently and give more options to the buyer,” he adds.

That’s what makes the Renault-Nissan combine a worthy emerging competitor to market leader, Maruti, which has ruled the small car market for decades. “The success of the 800cc Kwid has been followed by the 1-litre version and now an automatic version, which is expected to be rolled out by early next year, all of which is great. Kwid has to get it right on after-sales service, which is not easy. The big plus is that it has learnt from its past mistakes and seems to be on the right track,” says Sorabjee.

Thus, it has become imperative now for Maruti to build on areas such as imagery and product design that have not been its strength traditionally. “While Maruti has been outstandingly successful, they have still been conservative and not disruptive. That will have to change since the flavour of competition too has changed,” thinks Koshy. Some of that change in mindset is obvious when you look at brands such as Ciaz, Baleno and the Brezza. “At the higher-end, we are seeing some aggression. Maruti has smartly created them as standalone brands minus the Maruti tag,” he says before adding that the aggression needs to be displayed in the entry-car segment as well.

As for the Renault-Nissan combine, the journey ahead will be long and bumpy. They will need to design and adopt a multi-brand strategy, which will entail spending more money on marketing and distribution among other areas. This potentially is a huge outgo for a new entrant. “They have the resources and their approach so far indicates they are here for the long-term. If they make the mistake of not thinking big now, they will remain small,” warns Koshy.