Journalists and analysts typically spend the days after the Union Budget is presented picking over specifics in the Budget document and reading the fine print to understand various policy decisions. But what do you do when a perplexing decision is announced and there’s nothing in the documents — in fine print or otherwise — to explain the logic behind it? Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee’s intent to extend viability gap funding (VGF) to a host of new sectors is a case in point.

On the face of it, it sounds like a huge positive for driving investment in the country; after all, VGF is supposed to act like a force multiplier, helping government leverage its limited resources to create the maximum benefit in sectors where it matters most. But in the six years since its introduction, such funding hasn’t proved an unqualified success. Does it make sense to extend it further, in that case?

Spreading the light

When the government first announced the VGF scheme in 2006, the idea was to encourage private participation in resource-heavy infrastructure projects. By providing a capital subsidy for part of projects that are considered essential but commercially unviable, it essentially makes it worth the while for private investors to take them on. For instance, if a project was worth ₹100 crore and projections showed companies could make only ₹80 crore by building and operating it, the government would chip in with the remaining ₹20 crore.

Since the government can give up to 40% of the project cost as grant to get it executed, the monies involved in VGF are huge. Since 2006, over ₹20,000 crore has been either disbursed or considered for projects under the VGF scheme. In FY12 alone, the Centre has committed ₹11,996.87 crore as VGF for 111 proposals in the form of in principle/ final approvals.

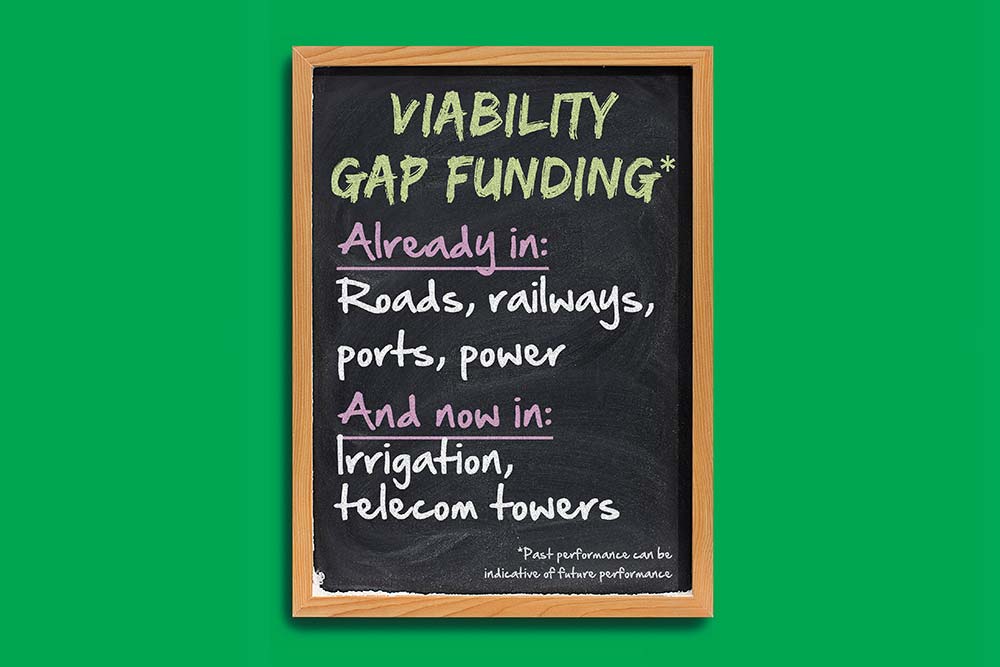

VGF is by definition reserved for public-private partnership (PPP) projects, which until this year’s Budget, were limited to specific infrastructure sectors like roads, railways, seaports, airports, power, urban transport and tourism infrastructure. Last fortnight, though, the ambit was extended to include irrigation, capital investment in the fertiliser sector, oil and gas storage facilities and pipelines and telecom towers. And that’s where the trouble lies.

Calculations gone awry

So far, close to 80-90% of VGF has gone towards road projects. But in several cases, the estimates of project cost and future cash flow — on which basis gap funding is considered and then granted — seem to be totally out of whack. In 2011-12, the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) had estimated that it would have to fork out ₹660 crore in VGF for about 16 highway projects (viable and unviable). Instead of doling out cash, the NHAI got back over ₹15,000 crore — and it’s not because the viable projects made up for the unviable ones.

Sample these. For the 88 km Kota-Jhalawar project, the NHAI had anticipated VGF of ₹228 crore. Instead, the highest bidder offered a premium of ₹30 crore. Similarly, the 45 km Nagpur-Wainganga project, the government got a premium of ₹191 crore against the expected VGF claim of ₹102 crore.

If it’s not bad enough that the sector that gets the most VGF is getting its math all wrong, questions have also been raised about the quality of such projects. Last year’s Economic Survey, in fact, blamed the upfront payment of VGF for the poor state of some national highways. “Due to this, some developers make so much profit at the start of the project and they don’t take adequate interest in maintaining the highways and don’t show interest in building the road properly,” the survey said. It also offered a solution: pay 10% of the gap funding upfront and convert the balance into an annuity to be paid in annual equal instalments for the next 20 years. That suggestion is yet to be implemented.

User charge conundrum

If VGF calculations go awry in core infrastructure sectors, the government’s chances of getting it right in more nebulous areas like irrigation seem especially dim. Gap funding for individual PPP projects is cleared by a special inter-ministerial government committee based on the potential cash flow of the project — how will it determine the cash flow from a dam or a telecom tower? “Extending VGF is a good decision on paper. But sectors such as irrigation and dams should be financed on an annuity basis rather than through VGF,” says Vinayak Chatterjee, chairman, Feedback Infrastructure and also chairman of a CII taskforce on infrastructure.

Even if the government succeeds in making irrigation attractive for private players, how will the user charges be determined? “We don’t even know whether the government is contemplating levying user charges in PPP-based irrigation and dam projects,” points out Nabin Ballodia, partner, KPMG. Moreover, if poor farmers are expected to pay for using irrigation facilities (as they will be in PPP projects), where will they get the money from — does this mean increased agricultural subsidies?

Irrigation firms aren’t too sure how VGF will work for them. Anil Jain, CEO, Jain Irrigation, says PPP projects in irrigation are still at a conceptual stage. PPP will mean that companies assume the role of a developer that supplies water to the end-user who has to levy user charges. “This is a highly sensitive subject. You cannot turn off supply if people don’t pay,” he says. The risk involved in user charges will have to be mitigated before the private sector plunges into PPP-irrigation projects.

The trouble with towers

Telecom operators, meanwhile, aren’t sure how to react to this windfall. There was much lobbying for the granting of infrastructure status to the telecom sector. That didn’t happen, but by extending VGF to telecom towers, one section of the sector has been granted de facto status. But it’s not really needed now. Over 80% of the telecom tower rollout is already done and an incentive at this stage makes little sense for telecom companies. “It is late by at least two years,” says BS Shantharaju, CEO, Indus Towers.

Telecom operators say they are still awaiting clarity on how the funding process will work but agree that the funding may come in handy for extending coverage and for capacity addition to existing rural areas a few years from now. For instance, as the user base grows, a group of 10 villages that needs one tower will require one more in a few years. At the time, the company putting up the second tower can avail of VGF. “In the normal course, this [setting up a second tower] may not happen. But VGF will ensure that it does,” Shantharaju says. Mahesh Uppal, director of consultancy firm Com First India, agrees. “VGF in telecom is arguably late. But there are 400,000 towers in India and it is estimated that 100,000 more will be needed, mostly in rural areas. VGF will be an incentive for them.”

But if the idea is to increase rural connectivity, there’s already a fund devoted to this: all telecom service providers contribute 5% of their adjusted gross revenue to the decade-old Universal Service Obligation (USO) fund, which is used to promote rural connectivity. Moreover, rural teledensity is currently at over 38% and operators like Bharti Airtel, Vodafone Essar and Idea Cellular have already made huge investments in rural areas without any government support so far. While Airtel has over 72 million subscribers in the hinterland, Vodafone is second with over 60 million users. For Idea, two out of every three new subscribers come from rural India and over 51% of its users are from the hinterland.

So, is extending VGF a good idea or not? Widening the scope of the funding plan certainly makes it look like the government is doing more than its share to encourage private sector investment but, really, it’s just another case of misdirection.