Made-in-China got terrible press in 2020, thanks to the spiked virus, which is still widely believed to have originated in China. We can argue about the virus’ origin till we turn blue, but we can all agree that the pandemic has caused a steady decline in the fondness for manufacturing and sourcing from the country. In fact, even before the pandemic sent everyone indoors, the appeal of the country as a supplier was fading fast.

The trade war with the US, which had begun in 2018, had exposed fault lines of what was seen as Chinese-dominated global trade.

While the country initially began with low-end manufacturing, in recent years, its ambition to play for bigger stakes by moving up the value chain, including AI and connected technologies, is hurtling it towards a head-on collision with developed-market competitors such as South Korea and Germany. In e-commerce, China has become the largest market in the world, accounting for more than 40% of global online transactions. Given the mammoth size of the Chinese economy, the administration is now steering the country towards domestic consumption-led growth. That just might have ramifications on global supply. Abhijit Mukhopadhyay, analyst, Observer Research Foundation, believes that around 32.6% of total cumulative Chinese exports till November 2020 have gone to the US and EU countries. Add that to the exports to Japan, Canada, Australia, and the UK, the number goes close to 45%. On the other hand, China itself is not import dependent on these nations, with 16% of its imports coming from non-trade partners and smaller economies. Which means, the developed economies depend more on China than the other way around.

That realisation hit companies and countries hard about five years ago, when several Chinese plants saw shutdown on account of environmental clampdown by the government, but it hit even harder as the pandemic gripped the world. In manufacturing, China accounts for 30% of the world’s output, and fears of supply-disruption turned real when COVID-19 lockdown ended up disrupting the supply chain of 94% Fortune 1,000 companies.

Indeed, it is a lopsided trading game, and countries and big corporations have woken up to the dangers of it. They have been trying to correct the tilt with a “China+1” strategy. And the pace is accelerating.

In April 2020, Japan announced a $2-billion subsidy programme for manufacturers who wanted to relocate back to Japan and another $230-million for those who want to move from China to any other Southeast Asian country; and South Korea has said it will spend $95 billion to build local capabilities in high-tech equipment.

Earlier, companies focused on low cost and reliable supply, but the intent now is to diversify their sourcing. “This is partly under pressure from their governments, and, partly, to derisk their reliance on China,” says S Ramakrishna Velamuri, professor, China Europe International Business School. A survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in South China showed that 64% of US corporations were considering moving their production out of the eastern powerhouse. They are concerned about rising labour costs and China’s decision to pivot its economy from exports towards domestic consumption.

So, there is this mass migration of industry underway. Can India profit from it? The country’s exports over the past decade have been hardly impressive, hovering around $300 billion. As percentage of GDP, it fell from 17% in 2011 to 12.4% in 2018. And its share in world merchandise exports ranged between a meagre 1.5% to 1.7% over the same period.

Perhaps, this is our chance to grab a seat at the table. Our success depends on answers to two questions.

First, can India swing the shift in its favour by scaling up domestic enterprises to cater to this new demand from global customers? Second, can it attract a higher share of investments from global companies, while also bringing in technology and building local supply sources? For both, action on the ground gives rise to optimism. As for the first, there is the growth seen in specialty chemicals industry, of more than 25% compounded over the past five years. These companies are still going strong with aggressive growth plans, seizing the opportunity created by high tariff barriers on Chinese exports to the US. But specialty chemicals could be seen as a unique case — where India’s prowess in chemistry shook hands with a world actively seeking an alternative to China. But then, there are also companies such as Dixon Technologies and Amber Enterprises, which have seen high-powered growth over the past few years on the back of contract manufacturing of consumer durables for global brands.

For the second, there is the government’s production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme in segments like mobile manufacturing and IT hardware that has attracted foreign investors. Sixteen proposals including three manufacturing partners of Apple — Hon Hai (Foxconn), Wistron and Pegatron — selected by the government committed to invest a cumulative sum of around Rs 110 billion to manufacture mobile phones worth Rs 10.50 trillion over the next five years. Last year, despite being a pandemic year, investments of Rs 13 billion materialised on the ground and produced goods worth Rs 350 billion in the first five months till December 2020, according to the ministry of commerce and industry. Samsung and Rising Star, and local players Lava, Bhagwati (Micromax), Padget Electronics (Dixon Technologies), Optiemus are some of the companies waiting to invest.

Can this initial momentum turn the tide in favour of Indian manufacturing decisively? The second wave and the cascading effect on economic activity has most certainly dampened business confidence. “Investments are delayed, but they are not off the table. Before the second wave of pandemic, we saw several companies from Japan, Korea, Germany and US, who were in discussions with potential Indian partners, spanning areas such as auto components, energy equipment and capital goods. The business models range from contract manufacturing, technology licensing to manufacturing JVs,” says Suvojoy Sengupta, partner, McKinsey & Co. Although there are concerns about demand destruction, the bigger worry is the government’s ability and willingness to walk the talk in terms of putting incentives on the table. “So far, there seems to be no change of track. The way out for India from growth-starvation is to spur employment by gunning for higher exports,” says an economist from a prominent foreign brokerage.

Cranking up production

The Centre’s ambitious scheme laid out last year involves rolling out Rs 2 trillion-worth of incentives over five years beginning FY20 to 13 key sectors, such as mobile handsets, pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Totally, nine PLI schemes have got cabinet approval so far. The first three were approved in March 2020 and these were followed by another 10 schemes in November 2020. Of these, the previous three schemes have been notified, and six of the 10 have been approved by the Cabinet.

A Credit Suisse report in November 2020 stated that the scheme will add 1.7% to Indian GDP by financial year FY27 and highlights that bulk of the additional $144 billion sales across 13 sectors will be exported, thus shrinking the country’s trade deficit by $50 billion. India’s trade deficit stood at $98.56 billion for FY21 and $15.24 billion for April 2021. “India’s incentive scheme will make the country number one in mobile manufacturing, or at least a close number two by 2025,” said Pankaj Mohindroo, chairman of the India Cellular and Electronics Association (ICEA), an industry body comprising smartphone majors such as Apple, Oppo and Xiaomi. He believes the phone makers will be accompanied by a host of smaller sub-assemblers and component makers, thus expanding the sector to 7x its current size in the next five years.

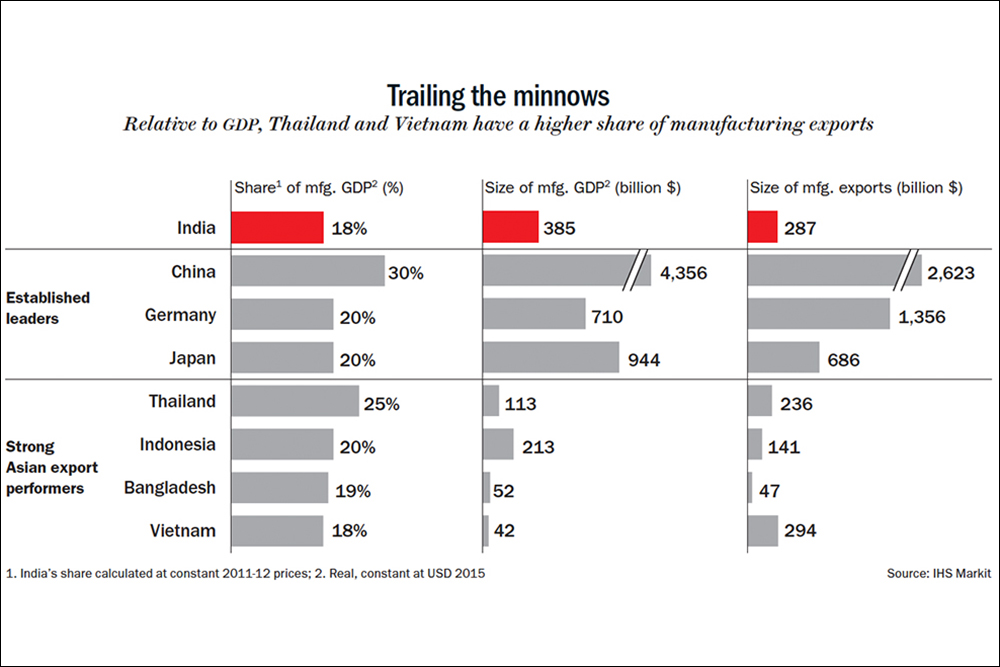

That is certainly the hope, for India has been a laggard in not just exports but also overall manufacturing so far (See: Trailing the minnows). Last fiscal, manufacturing constituted 17.4% of India’s GDP, little more than 15.3% from two decades ago in 2000. By comparison, Vietnam’s manufacturing sector more than doubled its share of GDP during the same period.

That is certainly the hope, for India has been a laggard in not just exports but also overall manufacturing so far (See: Trailing the minnows). Last fiscal, manufacturing constituted 17.4% of India’s GDP, little more than 15.3% from two decades ago in 2000. By comparison, Vietnam’s manufacturing sector more than doubled its share of GDP during the same period.

India’s manufacturing sector woes are deep rooted, with ease of doing business low and cost of doing business high, making companies uncompetitive compared with peers in other nations. While one can argue whether the 13 value chains shortlisted are too many or aren’t well-balanced, that approach seems the only way forward to generate fast growth.

One value chain at a time

The concept of value chain was first introduced by Michael Porter to gauge how companies perform various activities from start to finish, when they deliver a valuable product for the market. Extended to industries, it is the idea of seeing an industry as a system made up of sub-systems, each processing input into output involving money, machines, labour, land, administration and management. Since the 90s, a value-chain based approach came to define how various countries built competitive advantage for themselves.

This approach means ensuring that government policy, right from tariff protection, tax benefits and incentives for skill development and infrastructure, is aligned to support the creation and growth of the whole ecosystem. “This will be much faster than trying to fix the ease of doing business across the board. The latter may be a long-drawn out and painful affair considering our track record and bureaucracy,” says Sengupta.

In India, the auto sector serves as a good playbook. Maintaining high import tariff, India was able to attract global companies to invest in the country as well as drive localisation. Thus, the industry was able to become globally competitive and now exports of automobiles and auto components totals about $25 billion even as tariffs have systematically declined. While the big passenger car and two-wheeler makers, and component suppliers all derive a significant part of their revenue from exports, the sector is also able to attract newer players.

Korean carmaker Kia Motors is a classic example. The company invested $2 billion over the past three years to set up its operations in India even as India’s car market was in a cyclical slowdown. Tae-Jin Park, chief sales and business strategy officer, Kia Motors India, says: “India is not only an excellent manufacturing destination but also a potential export hub for automobiles, given a large pool of quality labour and the geographical advantage.” Now, in addition to the domestic market, Kia is exporting made-in-India vehicles to over 70 countries. Kia wants to develop India as an export hub, raising the share of exports from the current 15-18% of total production to 20% this year itself.

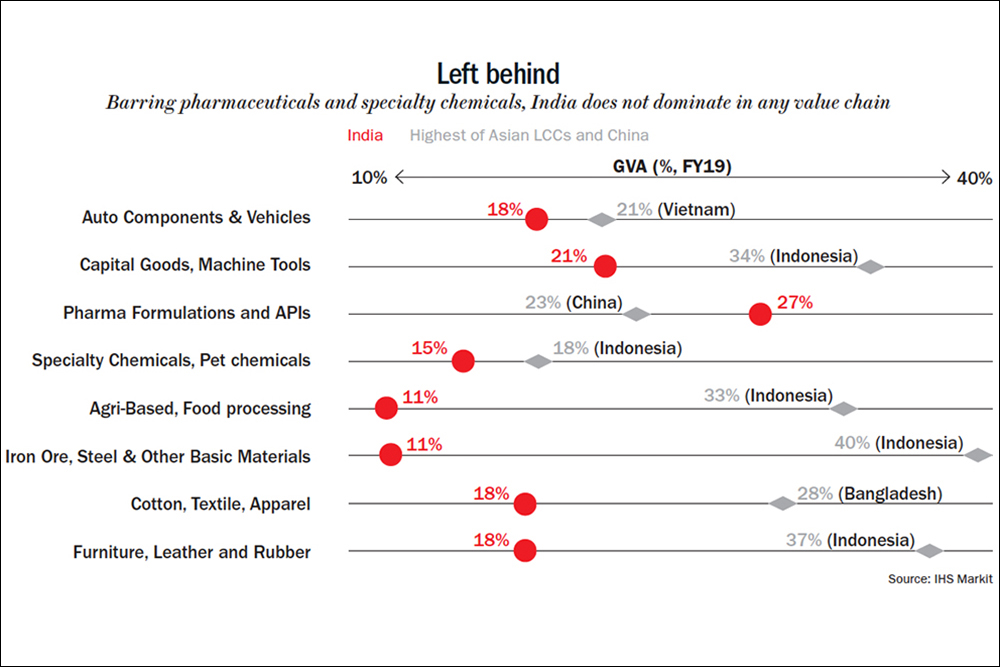

Currently, in automobiles and auto components, India’s share in gross value addition among Asian exporters stands at 18%, a notch below Vietnam which is the lowest cost country in this value chain at 21%. Barring pharmaceuticals and specialty chemicals, where India has a lead, it does not truly dominate in any value chain (See: Left behind).

Currently, in automobiles and auto components, India’s share in gross value addition among Asian exporters stands at 18%, a notch below Vietnam which is the lowest cost country in this value chain at 21%. Barring pharmaceuticals and specialty chemicals, where India has a lead, it does not truly dominate in any value chain (See: Left behind).

“Taking a cue from how other countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam have built their competitiveness, India has the potential to increase value add 3x by focusing on end-product quality and branding, greater localisation of end-to-end value chain, and sharp focus on competitiveness of exports,” says Sengupta.

In the two big value chains where PLI scheme has been announced, India faces an uphill task in driving localisation in electronics, but pharma may be an easier fix, relatively.

Electronics gotta be discrete

As for mobile handsets, there is already skepticism about whether component manufacturing will shift to India. Currently, 90% of mobiles sold in India are assembled here, but most components are still imported, which translates into a value addition of less than 10% by the mobile assembly and testing units. Unless the sub-assemblies and discrete components (components that go into subassemblies) shift production, and some of these components are localised, the assemblies will not stick. Assembly lines are largely modular and can be easily shifted overnight, and these will typically shift to where return on investment can be maximum. “There will always be some risks. It’s a trade-off, but we have to start somewhere and build on things,” says Sengupta.

Though the government has asked the handset manufacturers to define what level of localisation they will achieve, it is still not binding on them to do so. Either way, driving localisation is a harder ask in the electronics value chain today, compared to automobile components a few years ago, for two reasons. In automobiles, the government itself took the lead in forging the joint venture with Suzuki and drove localisation systematically, and other players followed the lead. The two-wheeler market again was sizable and grew swiftly in India, and along with it, those components manufacturers took off.

Rajeev Karwal, chairman of Milagrow Robots, who has worked with MNCs such as LG, Philips, and Electrolux, proposes the same route for fab manufacturing as we took for autos. “When the government entered into a JV with Suzuki, it created a huge manufacturing ecosystem, including component makers. The same can be re-created in fab manufacturing, which has so far not taken off because of huge investments required to create a chip.” While Karwal recently passed away due to COVID-19, his suggestion about the government making direct investments is debatable as components manufacturers have already scaled capacity in other countries — Taiwan and other Asean countries for sub-assemblies, apart from China itself; and Japan and Korea for discreet components — which makes it harder to migrate to other locations. “Electronics is a globally integrated supply chain and nations specialise in specific components, and it is hard to relocate them,” says George Paul, CEO, MAIT.

The problem is more acute when it comes to IT hardware because India has zero tariff, which means there is no incentive for companies to set up capacity here. “On top of that, the IT hardware market globally has been flat for the past six years, meaning there is enough capacity in the world already. Therefore, companies are less motivated to come and invest,” says Paul. But IT hardware is of strategic importance, for computers are at the heart of all critical infrastructure from power and telecom to passenger vehicles. “The outlay has to be a lot more and so should be the incentives,” says Paul.

Incentives aside, the global experience in relocating capacity has not been encouraging. While Vietnam has been hugely successful in attracting foreign investments, its effort to grab a share of component manufacturing has met with little success, and that says a lot. In the case of mobiles, besides getting a share of some low-end products, such as plastic cases for mobiles, the country has not been able to pull component manufacturing from other locations including China. That is why it has forged a free trade agreement with China, so it can continue to import components cheaply and maintain its share in assembly and testing.

Pharma’s small-scale problem

In pharmaceuticals, India already has a fairly strong formulation business with 12% global market share. The current incentive plan for APIs is critical, to bring back some of this manufacturing back and ensure the supply chain for our formulations business is protected. We cannot afford a situation where drug intermediate and API supplies are disrupted, because if that arises, the axe will fall not just on generics exports but also on domestic medicine supplies.

But replacing China here is tricky considering the scale they have already built around several products, and their pricing policy wherein, with depreciated facilities, they can really crash prices. For India to become competitive in bulk drugs, the scale of operations will have to be increased significantly. “If we can’t meet Chinese scale and price or the strengths of the developed world, then we won’t offer any real benefit or incentives for the developed world to seriously source from or outsource to India,” says Raja Ram, former managing director of Sigma Aldrich India, now Merck KGaA. In his last role, Ram spearheaded supply chain for Asia Pacific, “It is too late to mimic China,” he adds.

The current investments of Rs 50 billion coming into API manufacturing will make the country self-sufficient, but the companies’ price competitiveness will be critical to retain our competitiveness in generics overall. Pharma companies are willing to pay a small premium to diversify their sourcing, but it will be more like a transition premium that will have to be bridged eventually.

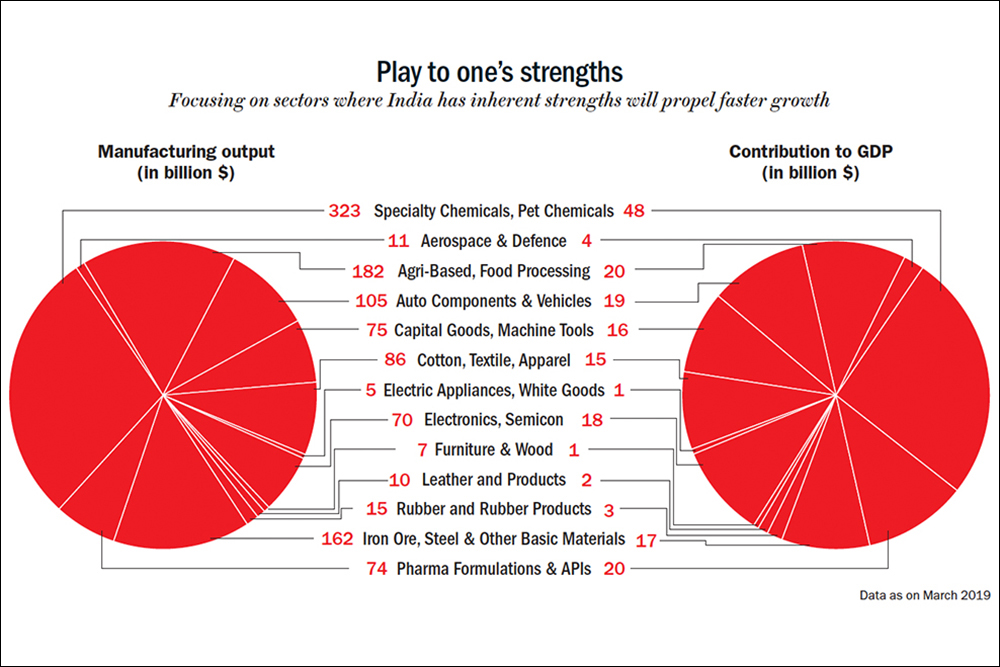

A better opportunity for India to tap is specialty chemicals with the country’s strong chemistry capability (See: Play to one’s strengths). This may not be huge by volume but can still be a sizable opportunity and profitable with distinctive competitive advantage. “If our niche is complex chemistry, then let us focus on that and not try to be everything to everybody. Complex chemistry has the added benefit of not requiring very large-scale production capacity, and they are also less price sensitive. So, there are lesser concerns from the already depreciated large-scale production capacity of China and its hidden subsidies,” says Ram.

A better opportunity for India to tap is specialty chemicals with the country’s strong chemistry capability (See: Play to one’s strengths). This may not be huge by volume but can still be a sizable opportunity and profitable with distinctive competitive advantage. “If our niche is complex chemistry, then let us focus on that and not try to be everything to everybody. Complex chemistry has the added benefit of not requiring very large-scale production capacity, and they are also less price sensitive. So, there are lesser concerns from the already depreciated large-scale production capacity of China and its hidden subsidies,” says Ram.

There is no government incentive plan here, but that is probably not as important as shared infra structure where companies can come and get their business up and running quickly. The IKP Knowledge Park in Hyderabad is a good example, which offers ready-to-use laboratories with common infrastructure from cafeteria, cold room and a chemical storage building to guard pond for effluents (ponds that check the flow of untreated effluents into outside environment).

If this is the formula to propel research, innovation and batch processing of specialty chemicals, acquisition of land and making essential clearances easier is the way to attract investors in other areas of manufacturing too. For now, the government is focusing on making this entry smooth for FDI.

The India pitch

Deepak Bagla who heads Invest India, the national investment promotion and facilitation agency, which is the first point of contact for foreign investors, is peeved with the narrative that India is losing to Vietnam. “The onshoring of supply chains has just started, this is just the tip of the iceberg,” says Bagla. Since the lockdown, Bagla and his team have hosted multiple roadshows across sectors. “We have gone sector by sector. In electronics, there are six states which have a good ecosystem, so these were given 10 minutes each to pitch directly. The CM and chief secretary are all part of the pitch,” says Bagla.

While the pitching is an ongoing exercise, FDI inflows grew 9.3% to $81.3 billion in FY21. Nearly 60% of the total investment came from Singapore, US and Mauritius. Nearly half or 45% came into computer software and hardware industry, but much of this came into digital ventures rather than manufacturing.

Bagla strikes an exuberant chord saying: “The velocity of money will keep increasing in the coming years, thanks to the PLI scheme. Our neighbouring countries’ have reached the top of the curve. We are just at the beginning, and anyone doing greenfield investment has to think how it will be five years later, not today.”

The government has to think of five years from now too, for which several fixes are required. “Entry and exit are probably now easy but living through business is far more difficult in India,” says Janardhanan Ramarajulu, vice president, regional head, South Asia and Australia, Sabic. He echoes the sentiment of most corporate chieftains in India. What he is talking about is not only the cost of logistics and inventory, but the additional establishment costs required to deal with bureaucracy.

Except Vietnam, where wages are about 10% lower, India continues to have the advantage of cheap labour but lags far behind in productivity. China is 3x costly and other countries such as Indonesia and Thailand also have higher wages. Compared with India, manufacturing productivity in Indonesia is 2x high; in China and South Korea, productivity is 4x higher, according to McKinsey data.

The recent episode at Wistron is an extreme example of how things can go awry and highlights the need to strike a balance between the prevailing levels of labour productivity and the expectation of companies that are investing. “These are not easy issues to tackle. But we certainly need to think harder about increasing the number of working hours and bettering productivity standards to be competitive,” says Paul. As has been proved, cheap labour cannot be a significant advantage in the long term since countries less developed will keep moving up the economic ladder and with it, labour costs will keep climbing too.

Apart from upskilling the workforce and transitioning to more value-added categories, domestic companies will have to work on building scale and trustworthiness. In fact, at the heart of the problem facing Indian manufacturing companies is return on capital. Money begets money, which means, unless you are profitable, you cannot power growth. And unless you invest and build scale, you cannot be globally competitive and sustain a profitable enterprise. Unfortunately, most companies in Indian manufacturing struggle to earn a return more than their cost of capital. According to McKinsey, over the past four years, from 2016 to 2020, sectors that saw healthier return saw an increase in invested capital; but out of the top 1,000 manufacturing companies, 700 earned a return that was less than their cost of capital in 2018.

Partly, the low return is from structural factors such as high cost of credit, power and infrastructure, and inefficient logistics, all of which escalate operating expenses — these are what the government now is compensating for through the PLI scheme. But the other big reason is the lack of scale. “The small, fragmented companies that make up some value chains cannot operate productively, let alone at peak efficiency; cannot innovate quickly enough to keep up with competitors; and cannot command price premium because they lack strong brands,” notes Sengupta.

Overall, the government has a long to-do list to work through and companies, a shorter one, before India becomes a compelling manufacturing destination. Considering the lead China has established and how other competing nations have grown in specific value chains, existing spaces are extremely competitive and taken. Snatching away share from others will be challenging, since every export-oriented nation not only wants to protect its own turf, but also wants a piece of the slice China may yield. India’s trump card has always been the large local market but that too is losing its relevance, considering countries such as Vietnam that offer a gateway to European Union with FTA.

Sure, the PLI scheme is a good start to regain ground in manufacturing, but it will only buy us some transition time. That done, India will need more than an incentive scheme to look appealing and that means more fundamental change on the ground.