A deafening silence filled the conference room at KKR India’s Mumbai office when the question was raised. The senior management, which included Henry Kravis and George Roberts, the firm’s co-founders, were visibly upset about its lending business in India. In 2018, KKR India Financial Services (KIFS), the wholesale lending arm, was in a state of disarray.

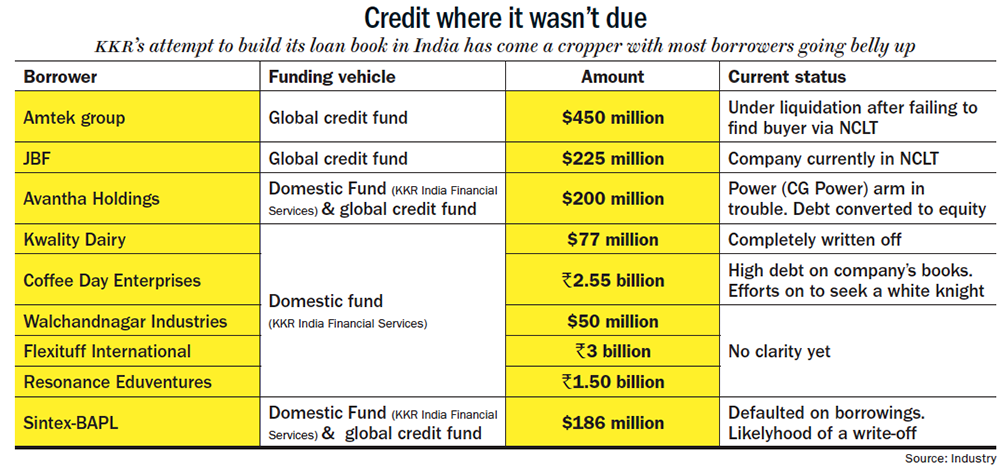

What was meant to be a routine strategic review meeting was now taking quite a different direction. Over the video conference, the US team, seated at the New York headquarters, did not mince words. “Can someone please explain to us how you are losing capital in the credit lending business?” asked the two co-founders almost in unison. The team in India led by Sanjay Nayar, KKR India’s CEO, seemed to have been caught off guard. Some big-ticket investments were in danger of being completely written off and there was no defence. Amtek, Avantha Holdings and JBF Industries were the bad bets, followed by a smaller debt to Kwality Dairy. Together, this added up to over $850 million (See: Credit where it wasn’t due). That video conference ended quietly, but the dissatisfaction was conveyed loud and clear.

KKR & Co’s Kravis and Roberts are a feisty bunch. If they weren’t, they wouldn’t have ended up building a private equity powerhouse. Their then record takeover of American conglomerate RJR Nabisco in 1988 for $25 billion inspired a book and a movie titled Barbarians at the Gate. “Barbarians” emanated from the war cry of noted buyout artist Ted Forstmann, who felt left behind by the KKR co-founders’ aggressive leverage to fund the buyout. It is a bit ironic that the same intensity, but in lending, is now causing its Indian arm much grief.

KKR & Co’s Kravis and Roberts are a feisty bunch. If they weren’t, they wouldn’t have ended up building a private equity powerhouse. Their then record takeover of American conglomerate RJR Nabisco in 1988 for $25 billion inspired a book and a movie titled Barbarians at the Gate. “Barbarians” emanated from the war cry of noted buyout artist Ted Forstmann, who felt left behind by the KKR co-founders’ aggressive leverage to fund the buyout. It is a bit ironic that the same intensity, but in lending, is now causing its Indian arm much grief.

In 2009, KKR was one of the first global PE firms to offer debt financing to Indian firms through KIFS and through its global credit fund. In both, many transactions have gone awry. It was not an abrupt edge of a cliff, more a downward spiral which began with the need to grow the loan book at any cost. In this urgency, KIFS backed the wrong promoters and offered loans with terms hopelessly in favour of the borrower. The lending business is today staring down a chasm of over $1 billion.

Its loan book is at Rs.58.8 billion, nearly 2x what it was five years ago, but the price exacted has been high. The NBFC has faced a rating downgrade, senior management has left in droves and there is closer scrutiny from the headquarters in New York. A broad estimate suggests that, in the 30 odd debt deals done by KIFS in the past three to four years, the NPA proportion is as high as 50%.

Worrying symptoms

The discord set in about three years ago. In 2016-17, the parent company began getting impatient and wanted to monetise their $200-million equity investment as they felt trouble brewing. But Nayar and BV Krishnan (former KIFS’ CEO) assured them that they were sitting on a lot of untapped potential. They said, KIFS’ loan book of $700 million could easily double to $1.5 billion. The top brass at KKR decided to wait, and for the senior management at KIFS, the only way to achieve that was to lend even more aggressively.

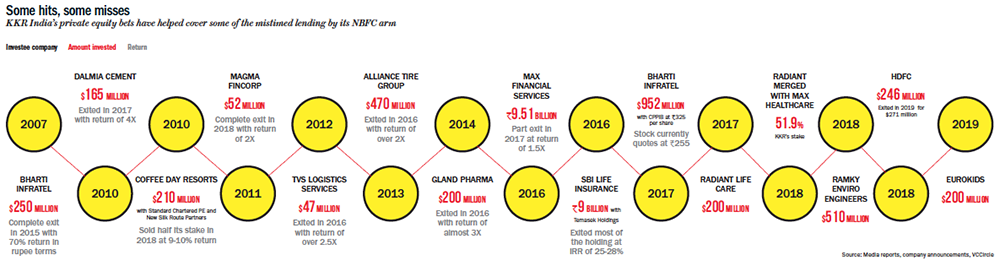

Debt financing is only one of three businesses of KKR India. While the first has run into trouble recently, the other two verticals – PE and real-estate financing – have done much better. The first, started in 2006 with the buyout of Flextronics, has deployed $2 billion and returned around 12% annually. The second, KKR India Asset Finance, opened for business in 2014 with Singapore’s GIC coming onboard the following year as one of the investors. Its $400-million loan book is primarily invested in housing projects across metros. Till date, it has invested more than $1.5 billion in various projects and has earned an average return of 10% annually.

At KIFS, the lending business was driven completely by Nayar with Krishnan by his side. Bankers say every deal out of India needed to have the “support and blessings” of the two men. Nayar who built KKR India from scratch had brought along his trusted colleagues from Citigroup, which included directors Tashwinder Singh and Mayank Gupta, besides Krishnan. “KKR India has been run like Nayar’s fiefdom,” says an insider. In fact, dissent didn’t get you far. “Nayar would choose the borrowers and was known to override any objection from his staff,” he says.

Peer conversation revolved around: “What are two bankers doing running an investment shop?” An NBFC veteran explains why this matters. “Both Nayar and Krishnan come from a banking background, in which lending is based on relationships. But in investment firms like KIFS there is no repeat business. Funds have payment deadlines.”

In a 2011 interview to Fortune India, Nayar asserted he was consciously steering the KKR Indian operations away from a typical, transactional PE firm. KIFS would be more accommodating, offering products that Indian entrepreneurs wanted such as flexible deals and growth capital. “We can be a pure PE firm later,” he said. Nayar had envisaged KKR’s future here as a merchant banking firm, that would advice promoters across industries.

Industry insiders may accuse him of being blunt, but in that interview he stressed on the importance of humility while dealing with clients. He had said that KKR is not “God’s gift to the promoter. They have to want us.” Nayar believed in being patient with the borrower, and that this philosophy was in line with what KKR’s founders wanted. “Unlike what you guys think, Kravis and Roberts aren’t pushy dealmakers,” he had said.

All went well initially, with Nayar registering success on some of the private equity deals – among these were investments in Alliance Tire Group, Dalmia Cement and Gland Pharma. In the early days, the $89 million lent to Chennai-based Apollo Hospitals is said to have yielded a very impressive return (See: Some hits, some misses).

Till 2015, the rapport between KKR India and its parent was solid. In 2016, the cracks began to appear. “Borrowers began running into corporate governance issues or their weak business models started to falter,” says a person familiar with the goings-on. A strain began to build between KKR and its Indian operations, he says.

Till 2015, the rapport between KKR India and its parent was solid. In 2016, the cracks began to appear. “Borrowers began running into corporate governance issues or their weak business models started to falter,” says a person familiar with the goings-on. A strain began to build between KKR and its Indian operations, he says.

In mid-2017, at a company offsite, Nayar and Krishnan made an effort to reassure everyone. They spoke eloquently of how other non-banking financial companies (Edelweiss Group was repeatedly mentioned) were valued at 3X their book. The plan was to quickly list KIFS and ensure the parent walked away with a handsome profit. There was also a chance that the top brass, in possession of KIFS stock, would have made a killing; it is roughly estimated that Nayar alone could have made at least $20 million. However, conversations with investment bankers revealed that at least a billion dollar book was required and, by the end of the year, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) agreed to infuse $100 million in KIFS for a minority stake. KIFS was approximately valued at $600 million, and the listing seemed on course.

The entire plan came apart quite abruptly. Just a few weeks later, a series of bad news around KIFS’ borrowers broke. Both Amtek group and Kwality were the first to flash red and CG Power, a part of the Avantha group, was not looking good either. KKR & Co. read the signs and decided to put the entire loan book on the block. A host of firms were reached out to (Avendus being among them) though nothing came of it. “The quality of the book was the issue and nobody was willing to touch it. The real trouble started then and has steadily deteriorated,” says a person who has closely tracked the development.

The team here, still obsessed about growth, decided to look at smaller NBFCs to buy out and zeroed in on Svakarma Finance. Started in 2017, this Mumbai-based entity was run by former Citibank executives and the arrangement was that KIFS would invest $50 million for a majority stake. Discussions reached a decisive stage in mid-2019 and when approval was sought from KKR’s top brass, it was immediately rejected. HQ was livid and emphasized bringing the existing loan book back on track. Hence, the deal fell through.

For a few years, Nayar and Krishnan had been hard selling the India story to their top management with a reasonable degree of success. “For a company of KKR’s size, the write-off in India was an insignificant amount. What troubled the parent was sloppy assessment of credit risk,” says the person quoted earlier.

KIFS’s fault was to focus singularly on growth capital. A veteran from the NBFC industry says, “KIFS did not diversify its risk portfolio, it followed the same lending pattern for its bets,” he says. The focus was on high-yield. Within that category of risky capital-starved companies, KIFS’ strategy was to shortlist familiar promoters and then back them aggressively. “In many ways, it was an approach based on relationships and intuition,” he says.

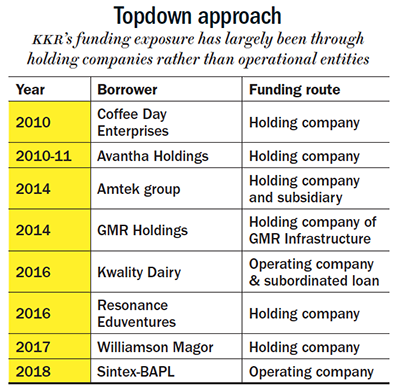

Besides poorly assessing credit worthiness, the NBFC seemed to have been taking undue risks. For one, it lent money to the holding company, and rarely to the operating company. This meant that, if the borrower wished, this money could be spent on any of the operating companies (See: Topdown approach). However, a KKR India spokesperson who partly replied to our detailed questionnaire, says, “Globally, the alternative private credit market, involves extending loans to holding and investment companies as well as operating businesses. In India, our strategy remains the same.”

Besides poorly assessing credit worthiness, the NBFC seemed to have been taking undue risks. For one, it lent money to the holding company, and rarely to the operating company. This meant that, if the borrower wished, this money could be spent on any of the operating companies (See: Topdown approach). However, a KKR India spokesperson who partly replied to our detailed questionnaire, says, “Globally, the alternative private credit market, involves extending loans to holding and investment companies as well as operating businesses. In India, our strategy remains the same.”

The second niggling bit about KIFS’ lending practice was that it demanded little or no collateral from its borrowers. It would have frayed a few nerves at the New York HQ, but the Indian office calmed them by saying that the interest charged was higher. “NBFCs would charge 12-13% with collateral and KIFS would take 16-17% with no strings attached,” explains a private sector banker. The concept of “high-yielding”, he says, struck the right chord and Nayar and team did not hold back. Often, the logic given out was that the borrowers were known to them from Citigroup and there was no cause for concern. But there were loans extended that, even today, beggar belief.

Bad practices

KIFS had placed a bet on the Amtek group, in 2014, when it was Rs.140-billion deep in debt. This was around the time group company Amtek Auto had made over 20 overseas acquisitions. The expansion must have looked impressive, but KIFS should have considered Warburg Pincus’ loss while investing in this group’s companies in 2010 and 2013. First, the PE giant lost 60% of what it had invested in Amtek India and, the second time, sold a part of its holding in Amtek Auto at a 70% loss. Warburg clearly saw trouble ahead and sold off. It is mind boggling why KIFS would lend to a group which was deep in debt – and where Warburg Pincus had stumbled – but it did. Soon, Amtek Auto defaulted on a Rs.8-billion bond repayment, failed in its bid to sell the business to London-headquartered, steel major Liberty House (did not make the upfront payment) and floundered with its restart last February. Finally, Amtek Auto went into liquidation, leaving its 100-odd creditors holding the can.

The cellphone rings twice before Arvind Dham answers it. The Amtek group’s founder hears you out and promises to call back, though he never does. Incessant calls to him, as one discovers, are only an exercise in futility. Either the calls remain unanswered or all one gets is a polite text saying, “Can I call you later?”

Perhaps you can’t fault him on this minor courtesy lapse. After all, it has been an incredibly tough ride for Dham. Creditors are getting anxious; the most anxious of the lot is KIFS. Through a combination of debt from its global credit book and India as well, KKR’s exposure to the Amtek group stands at $450 million, the biggest on its books.

Even the small-ticket deals have landed KKR India’s lending business in a spot. Take the case of Delhi-based Kwality Dairy, to which KIFS had agreed to lend Rs.5.2 billion. In the first tranche, Rs.3 billion was to be handed out. That was in mid-2016, and for at least three to four years, Kwality had been in the market scouting for investors. PE funds were showing little interest. That was odd given that some of the large players in the dairy sector were already in the midst of some serious fundraising activity (such as Carlyle investing in Tirumala or Westbridge in Hatsun Agro). A private equity veteran remarks that Kwality’s financials were always dubious and most funds managed to see that. “It is surprising that KKR decided to lend them money, when there was always concern about Kwality’s ability to manage working capital. It was quite well known that the company’s books were not clean.”

In October 2018, KIFS took Kwality to National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) for defaulting on a loan. The dairy company’s stock had crashed from Rs.115, when KKR had agreed to advance the loan, to Rs.9.8 that October and trades at Rs.3 now. Kwality is in the red by over Rs.32 billion with revenue slumping to Rs.21.3 billion. The KKR spokesperson says, “As reported by the resolution professional, large-scale fraud and misreporting in the company are the primary reasons that have led to loans to the company going bad.” The spokesperson adds that their credit to Kwality was only a portion of the first tranche of Rs.3 billion. Those tracking the development say that KIFS will be lucky to recover anything upwards of Rs.100 million, since this is a subordinate loan or a debt, which is low in priority if the borrower goes bankrupt.

In some cases, such as the Avantha Group, KIFS had a clause where debt could be converted to equity. That has not helped much either. In 2011, the NBFC had loaned Rs.10 billion for the group’s foray into power generation, among other projects. Once again, it turned out to be a bad bet. Neither did Avantha Power list nor did the two power plants generate any revenue once the coal allocation blocks were cancelled. Since then, Bilt has been trapped under a debt pile and CG Power has been trying to resolve corporate governance lapses, with understating of liabilities and advances being right on top. The CG Power stock that had been pledged by promoter Gautam Thapar gave KIFS a 10% holding in the company. But it quotes at Rs.12.65 today and, at a market capitalisation of Rs.7.90 billion – the stake is valued at less than a tenth of the loan amount. KKR India’s spokesperson says, “KIFS is a lender to Avantha Holdings with no credit exposure to any other group companies, such as CG Power and Bilt. We continue to maintain a debt claim against Avantha Holdings.”

Besides the ones above, KIFS’ list of troubled borrowers include GMR Holdings, Walchandnagar Industries, Williamson Magor and Resonance Eduventures. The few good ones are Apollo Tyres and Max Group. Otherwise, most are in serious financial difficulty, with no saying when (or if) they will be able to repay.

While these may speak of KIFS’ poor diligence process, there is one deal that raises an ethical question. The NBFC has extended a Rs.3 billion loan to Coffee Day Enterprises, even though KKR still holds 6% stake in it through its PE arm. “If you have already put money in equity and the company isn’t doing well, why would you hand out debt to the same promoter? It’s highly imprudent,” questions an investment banker.

Investor unrest

Not surprisingly, investors in KKR India’s NBFC are a miffed lot. Recently, KIFS reached out to its existing base of investors to raise a Rs.50-billion India credit fund. It was firmly turned away. “They want their money before anything else and have made it clear that any more participation from them will need to have the complete involvement of KKR’s headquarters and not be left to the local team,” says the banker quoted earlier.

In the beginning, the investors had been drawn in by the pedigree of the parent company and Nayar’s experience of having run Citigroup India. Above all, they were given the assurance that KKR India would have its nominee on the board of each investee company. “The presence of the nominee was meant to convey higher level of involvement and make the investors comfortable,” says a person familiar with the arrangement. The debt business had participation from the likes of Sunil Kant Munjal of Hero Group through his family office, veteran investment banker Hemendra Kothari whose mutual fund business has put in the money, apart from names such as State Bank of India, IDBI Bank and Bank of Baroda.

But the nominee-on-the-board promise remained unmet in a few companies. As luck would have it, these turned out to be ones with poor corporate governance. The troubled Kwality Dairy is only one instance. In the case of Sintex-BAPL, Tashwinder Singh was on the board as long as he worked with KKR India till mid-2019. That position has remained unoccupied since. JBF Petro, which KKR has dragged to bankruptcy court, too, had a KKR nominee only for less than a year. There is none now. At Amtek, the nominee joined the board and left soon after.

Investors “are extremely upset about the reckless lending” by KKR India, says a person close to the development. In the midst of such reckless lending, not having a nominee on the board must feel like being placed on a rollercoaster blindfolded. It’s not fun if you don’t trust the safety harness.

On March 31, 2020, a Rs.15 billion repayment to investors is due. This is loose change for the parent. But the rub is that, KKR & Co. is still noncommittal. Today, a team from HQ shuttles between New York and Mumbai, talking to a host of foreign banks based in India to raise the repayment due — a clear indication on who runs the show now.

Banking circles talk of KKR’s lending business in India being under review. The parent could even be considering winding down the business. As one banker says wryly, “It may make sense for them to get back a few years later when they understand the market a little better. Perhaps, they will be a lot more cautious then.”

KKR’s India operations aimed at being every entrepreneur’s partner. Nayar had said, in an earlier media interaction that he was looking at a more collaborative role. It is well to be a friend in need. But a friend must also demand that a person (or a company) be the best version of itself. Did KKR India and KIFS fail in being a good collaborator, who was unafraid of being intrusive when needed? Or did they simply chase an unwieldy loan book down a blind alley? Either way, the clean-up must begin fast.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This story appeared in Outlook Business' January 17, 2020 edition as the cover. As with all Outlook Business stories, we had done thorough due diligence and verified all facts to the degree possible. However, KKR's spokesperson has responded with the following statement:

“KKR is extremely disappointed with Outlook Business’ cover story published on January 3rd, 2020 regarding KKR’s credit business in India. We totally disagree with the narrative and the article is replete with multiple errors. KKR India Financial Services Limited (KIFS) is a leading non-banking finance company that is regulated by the Reserve Bank of India and rated “AA” (Stable) by CRISIL.

KKR recently committed an additional USD150 million to KIFS. In connection with this investment, Joe Bae and Scott Nuttall, Co-Presidents & Co-Chief Operating Officers of KKR, stated, “This commitment demonstrates our ongoing support of the KIFS franchise and its future prospects. Moreover, it solidifies KIFS’ financial position, allows KIFS to be proactive in a dislocated market, and reflects our confidence in KIFS and its mission to finance India’s homegrown champions.” Private lending in India is more important than ever, and India has been and continues to be an important part of KKR’s global growth strategy in Asia.

Dislocation in the Indian credit markets has negatively impacted NBFCs across the board in India. KIFS is no exception. However, KKR has been proactive in identifying and addressing credit issues in the portfolio and is a market leader in this regard. KKR looks forward to continue being a solutions-provider in the Indian market."