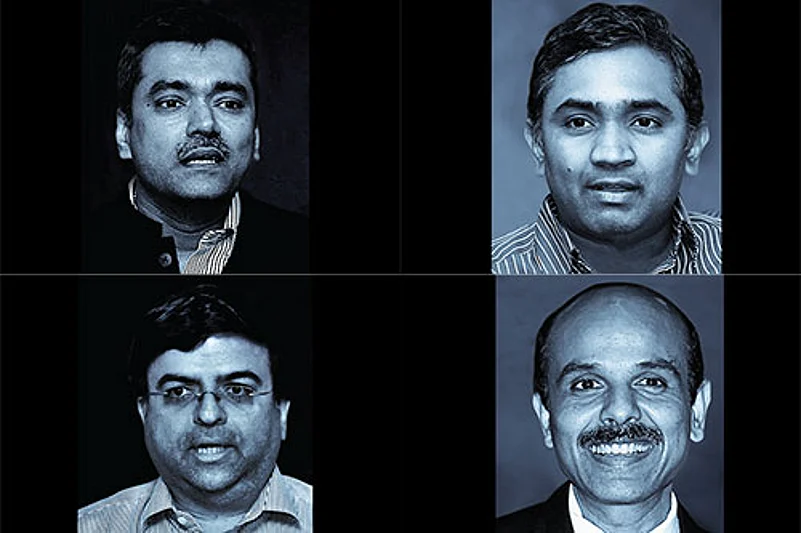

Can mobile technology be used as a transformational tool for access to good governance and efficient delivery of public services? This topic was in discussion at the Dasra Philanthropy Week held in Mumbai recently. Edited excerpts follow.

Ganesh Natarajan: I run a company that is primarily focused on digital transformation, which is the use of mobility, cloud, social media and big data in transforming corporates. It’s amazing to see how much potential lies there. I still remember speaking at a seminar 15 years ago where a Harvard professor spoke of a time when half of India was waiting for a telephone and the other half was waiting for a dial tone. And today, to talk about the 400 million-plus phones — and a billion in the not-so-distant future — is absolutely amazing. I’m here as a student of mobility and e-governance, as much as any of you.

One of the things that sparked my interest in the phenomenon is a conversation I had with two young, bright students three years ago. Anu and Punita had just graduated from UC Berkeley but were headed off to Hubli in Karnataka to set up NextDrop. Water is such a big deal in this country and if we can just make a technology-based innovation where every citizen in Hubli can know when the next drop of water is going to come, the whole government interface can become that much better. I was very interested as a person, we were very interested as a company and, today, we are working with them in Bengaluru along with the water supply board to see how we can build a big data source around the water problems.

Mobility is the answer and mobile phones will always be accessible. I think every person in this country will have access to mobile phones and if that can make some magic happen, we may not solve all problems but we will certainly go 40% of the way towards finding good solutions. So, I’m excited about this panel discussion. Let’s start with Vivek Srinivasan.

Vivek Srinivasan: I come from a really sleepy college called Stanford University and it is wonderful to be here with so much action and innovation happening. Thank you Dasra and the Vodafone Foundation for putting this together. When we think about mobile governance (m-governance), the first thing we think about is how governments are rolling out the use of mobile phones. But I will take a slightly different view. After all, we are the government. I want to talk about how citizens can leverage the power of mobile phones in making governments more responsive, democratic and accountable. A part of this impetus comes from my work with several rights-based campaigns in India, primarily the campaign to make education a fundamental right for every child.

There are two activities that I can think of. One is the way that mobile phones were used in the tremendously successful right to information (RTI) movement. The second is that invariably, in every activist network, you spend a lot of time trying to find out how things are happening on the ground. Are the policies that governments talk about actually taking place, are 24-hour primary healthcare centres really open, are essential drugs that are supposed to be at the PHCs really there? That form of collecting information from a large number of people is an essential part of activist activity and this is where mobile phones can make a dramatic difference.

One of the things that I am engaged in is an exercise where we try to make programmes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and the public distribution system (PDS) more transparent and accountable. The method we follow is borrowed from the social audits created by the RTI movement. For instance, if I am trying to get ration records, I go to beneficiaries and ask them if the records that state what they have been given are correct. This sheds light on the corruption present at the grassroots level because one of the main forms of corruption at the lower levels of the bureaucracy is fudged accounts.

So, you say you gave 100 kg of rice, when you actually gave 50 kg. Verifying this data with the beneficiary gives new impetus to shake up the system but the process of organising social audits with pen and paper is very cumbersome; you have to apply for the documents and it takes forever for them to come. There were many occasions when we had to stage a dharna to get the documents. There was one official who told me that he would rather part with his life rather than with his papers. Then, if you get the papers, it takes a great amount of time to make sense of them when all you’re asking is a simple question: how much grain were you given in the past five months?

Then, there is the explosion of mobile phones. So, even in Bihar, which is among the poorest states, every second family has a mobile phone. This allows us to show people the accounts that are available online, so they know how much money was given in their name, how many roads were laid or if a school has been constructed in their neighbourhood. This way, they can verify the information and do something about it. Another example is about monitoring. One of the groups that I work with monitors public health systems in Maharashtra. Traditionally, they used to do surveys. So, they would create formats, train people, take the formats to the villages, fill the forms, post them, do the data entry and then get the information out. When they would take it to the health minister, he would often say this data is eight months old, we have already changed the system. So, we enabled a system whereby we would tackle a single issue in a given month, and get feedback from people via SMS, reducing the turnaround time to around two weeks.

For policy work, it is good to have carefully carried out surveys on which you can reflect and try to change policy over a period of time but when it comes to implementation, you can get the feedback relatively quicker. But I would like to caution against one thing. A lot of technology project planners believe that if you just put technology out there, it will be used by anyone and everyone. I believe that for technologies to have a real impact, they need to have real action. You can’t just go on a helicopter and drop pamphlets that give people information; you have to tie information to action. In a country like India, where there is tremendous activism and lots of people fighting on the ground and sticking out their necks, creating technologies that they can use will be the most important way that they can create change. This is where I want to make a pitch for the people in this room. I have been hearing a lot about how we would want to support people who are non-confrontational. If you want governance, please support those who fight, who put their lives at stake.

I know that foundations and corporations aren’t always in a position to do so but we need to put our heads together and think creatively to support those who are actually willing to fight, because real change won’t happen in this country without somebody sticking their necks out.

Natarajan: Quick question for you, Srinivasan. Assuming that you put all this technology in place, train people and make sure they support the social sector, what happens if the government doesn’t listen?

Srinivasan: To say that the government does or does not listen in a binary is always wrong. The louder you are, the more they are forced to listen. There is always an element of resistance. The positive factor is that today, people are becoming more and more assertive and governments are being forced to respond more often than not. Fifteen years ago, who would’ve thought that Bihar will have good roads? Who thought PDS across the country would improve? All of this is in response to growing pressure from the people. So, I just like to think that governments do respond to people’s voices. The role of technology is to amplify these voices.

Natarajan: Thank you for that positive opening. What are your views, Mehta?

Nitai Mehta: I would like to put my views in two parts. First, for me and our organisation Praja, mobile technology and the internet can be a barometer for freedom. It is an instrument, a tool to measure the amount of freedom a country provides for its citizens. For instance, this tool was used widely in the Arab Spring.

The second part is how Praja has experimented with using this technology. We started our first project in 2003, when we launched the first online complaint management system for the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), in partnership with the corporation. Through this, we identified 95 typical complaints, gave them timelines and also said that if the work was not done, it would be escalated to the senior officer. We got feedback from the BMC — even from the more cynical municipal officers — saying that this has helped them perform better.

This was an initiative taken by a government organisation like the BMC to use technology to improve service delivery. But there is also a flip side. Ultimately, at the service delivery level, there is a human being who actually has to deliver. We used to get complaints about garbage lying outside someone’s house or office and the feedback from the corporation would say that it has been cleared but the garbage would still be there. We decided to carry out an audit to check. The BMC said 90% of the complaints have been resolved and the citizens said 50%. In Mumbai, there are 24 wards. In some, the gap between what the corporation and citizens said was smaller and in others, it was larger. This way, we knew the performance of the wards, so this became an interesting experiment that we still carry out.

The other thing is what the BMC has itself done. People in Mumbai know that two years ago, there was a programme through which you could use a mobile phone to take photographs of potholes in the city and the BMC would fill them up. That was a huge success. The BMC wants to carry this out for other services too, but it is hesitant because it fears that once this is out there, it will draw a lot more negative feedback than now.

Natarajan: Mehta, you are obviously using mobile technology the way it exists. But as part of these applications, whether it is for the BMC or something else, are there more features that could make them more effective?

Mehta: As far as features are concerned, it is all there. It is a question of how you use it. For example, mobile technology can be used in service delivery. I think that is an area that we really need to look at, whether it is birth certificates, getting an electricity or water meter, or even putting in an application for a factory or shop licence.

Natarajan: Balaji, there is a lot of talk that the government wants to throw out all foreign providers and create an environment where every Indian has a smartphone costing less than ₹5,000. Is that an opportunity or a threat?

P Balaji: Frankly, this government and the ones before it have done a lot to get foreign investment in the country. When, 21 years ago, I joined this sector [with the Tata Group], people told me I was on a suicide mission and I should have chosen Telco or Tisco and not these new-fangled entities. The reason why I mention this is because, today, in the operator space, you are talking about a 100% FDI bring-around. Vodafone is the largest investor in the country. Every year, we have invested close to $2.5 billion.

The Indian context has changed dramatically since the government decided to integrate the global economy and liberalise this sector. Today, forget ₹5,000, you can get smartphones for ₹2,000, so those barriers have been breached. That is what has led to this exponential growth of technology. These are devices with the same computing power that was in the Apollo missions in the 1960s. That is the power that you are looking at in the hands of people.

Along with that, it is the evolution of an ecosystem that has helped us get this far. As far as government policy is concerned, I have already spoken about players that came in with the belief that there was a lot to do in India. Entrepreneurs and innovators who decided to put their lives on hold to provide applications and batch services — as we used to call it in those days — to millions of people. That has borne fruit.

Natarajan: Thanks Balaji. If you look at your experiences and try to think of future natural collaborators for Vodafone, who would they be? Is it governments, civil society or entities like Dasra, or is it something else?

Balaji: We believe change starts at the last mile. Today, we are about 200 million subscribers strong. But this wasn’t always so. Over time, we have created capability to roll out networks. Technology is easy but adoption is the tough part. Today, we serve 2 million entrepreneurs who are actually retailers selling our product. A poor person is probably going and doing a top-up every second or third day. We would not be able to do this without an ecosystem that was available at the last mile. All you need to do is help people at the grassroots level with your experience. I just heard about how Dasra goes about building grassroot-level leaders. We actually identify panchayat heads and women, give them IT tools and make sure we can make a difference in the area.

Natarajan: Madhukar, your views on the future of collaboration?

CV Madhukar: Talking about the government and its adoption of technology, it occurs to me that when something as tectonic as what we are going through happens, there is a shift in power equations. Whether the government adapts to it little by little or is forced to adapt is for us to see. I want to talk about the stakeholders involved in making this mobile revolution happen. No matter how much power we have, the government is the primary enabler of what we need to do with technology. There are two situations — one is how much the government can do at the back end to enable itself with technology, to reengineer processes and make technology central to how work gets done in the government. The other is how much data the government is willing to share. The idea is that government has to put out data in a way for all of us to benefit from it much more than we currently do. That transition won’t be easy, but we are impatient and we should be.

The second stakeholder is the innovator of the technology. We would love to have more WhatsApps, Twitters and Skypes, more people thinking about how to make technology accessible. Then, NGOs. People use technology in different ways — who’d have thought that it would play such a crucial role for a group like Association for Democratic Reforms, which is so focused on electoral reform? Twenty years ago, who’d have thought that mobile phones would be a major part of how political parties run their campaigns?

Then there are private sector entrepreneurs — people who can take the big data available and convert it into something that makes sense to us. Take for example the data that the weather department releases,and convert that into an app that farmers can use — whether there are tides, rain or storms, the farmers would want to know. The private ecosystem is important. And, lastly, all of us as consumers and contributors have to use this technology. How much we engage is up to us and, clearly, some of us are very active and many of us aren’t. And then we, like all citizens, complain about governance. Not realising that, sometimes, we are not doing our bit other than voting once in a while. Even the things that are in our hands can make a difference.

Natarajan: Just as a closing thought, let me give you some ideas from my favourite book, which is not written by Amartya Sen, not written by Alvin Toffler but is a book that many of you may have read — Alice in Wonderland. If you remember the Red Queen’s party, there is this wonderful game they play called croquet. As Alice tries to hold on to the mallet while putting the ball through the hoops, suddenly you find that the mallet changes into a flamingo that raises its head. That’s technology.

Technology will keep changing, so you can’t expect a mallet always. Similarly, when you come down and hit the ball, that ball is your beneficiary. But it might run away, it’s not going to wait for you to hit it. The expectations of your customers or beneficiaries are going to keep changing and the hoops through which you knock the ball will keep changing. That is the beauty of this environment, all of us need to contend with never-ending change. If you make that happen, we can still talk technology and make that happen.