'Be A King’ goes the tagline. Ironically, a woman passes the crowded dimly-lit dance floor at a club and takes over the console. She’s a DJ, commanding their pulse with her beats. The theme continues, in a more recent commercial. This time, taking centre-stage is Siri Narayan, one of India’s handful female multi-lingual rappers.

There’s a streak of rebelliousness and a sense of breaking free in each of these narratives — a vibe that Budweiser’s parent AB InBev flaunts, be it in strategy or office interiors. “I have never been afraid to state my ambition and this company allows me to do so,” gushes the newly appointed South Asia president, Kartikeya Sharma, whose seat is at the centre of a massive white bow-shaped table, which he shares with other senior colleagues in an open-office structure.

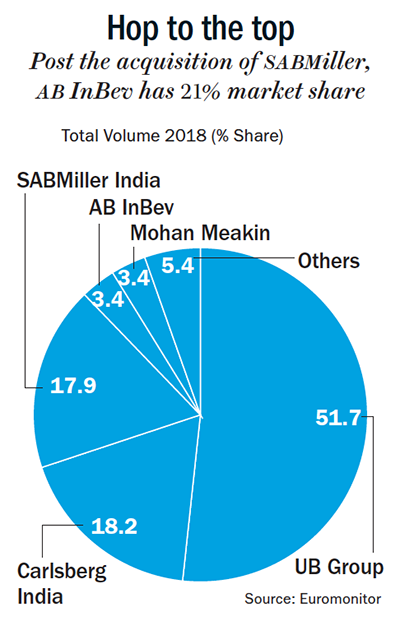

AB InBev is the largest beer manufacturer globally, brewing close to one-third of the world’s beer. But, despite its might and mammoth portfolio of nearly 500 brands internationally such as Budweiser, Corona, Beck’s, Hoegaarden, Leffe and Stella Artois, it has struggled in India since its direct entry in 2007. While Euromonitor data puts AB InBev’s 2018 share of the Indian beer market at 21.3%, much of that market share was a legacy gift that came its way, courtesy the acquisition of SABMiller by the parent in October 2015 (See: Hop to the top).

AB InBev is the largest beer manufacturer globally, brewing close to one-third of the world’s beer. But, despite its might and mammoth portfolio of nearly 500 brands internationally such as Budweiser, Corona, Beck’s, Hoegaarden, Leffe and Stella Artois, it has struggled in India since its direct entry in 2007. While Euromonitor data puts AB InBev’s 2018 share of the Indian beer market at 21.3%, much of that market share was a legacy gift that came its way, courtesy the acquisition of SABMiller by the parent in October 2015 (See: Hop to the top).

SABMiller India at the time of acquisition enjoyed around 20% market share, thanks to having bought Shaw Wallace’s beer brands such as Royal Challenge, Haywards, Hi-Five, Lal Toofan, Rosy Pelican and Kohinoor in 2003. SABMiller India’s own brands then included Castle and Knock Out (acquired from Mysore Breweries). Currently, on a standalone basis, SABMiller India still has 17.9% market share while AB InBev India has 3.4% (compared with 3.2% in 2015). In contrast, Carlsberg, which entered the market in May 2006, now has 18.2% market share. This uphill battle for AB InBev has been because of entrenched competition, missed opportunity and local market vagaries. Let’s examine each of these.

King of All Times

Having gained control from embattled liquor tycoon Vijay Mallya, the now Heineken-owned United Breweries (UB) has turned out to be a formidable competitor with 51.6% market share. Its Kingfisher beer lords over the market both in the strong and mild segments with 32.9% and 10% volume share, respectively.“Kingfisher is one of the oldest beer brands and it has taken them years to build their distribution network. In India, more than taste and branding, availability, pricing and distribution play a key role,” says Rahul Singh, founder, The Beer Café. When it comes to reach, UB is way ahead of its peers with 21 breweries across states while AB InBev has 15 breweries and Carlsberg eight.

An industry veteran, who does not want to be named, says that UB has been “lucky” to have competitors such as AB InBev and he means it as no compliment to the latter. India is one of the most complex markets in the world as well as heavily regulated, he adds, and most MNCs appoint expats to lead the businesses and they come with a global mindset. “Any classic international company would think they have fantastic brands and great quality and their consumer market research says that their brand scores really well. But, in India, what is the point of having a good product if you are not ‘allowed’ to be available or distributed everywhere,” he asks.

Now on, now off

Ignoring ground reality has clearly not helped. In addition to its joint venture in 2007 with Crown Beers where it invested in a bottling plant in Hyderabad, AB InBev also had a marketing and distribution agreement with bottling king Ravi Jaipuria’s RJ Corp, which the latter exited in February 2015, after nearly eight years. There were also news reports in 2010 about AB InBev wanting to sell off its brewery in Hyderabad as India was not a priority market post AB merging with InBev in 2008.

Due to this non-committal stance, AB InBev when it entered India just transplanted Budweiser into the local market. The premium positioning turned out to be a non-starter as the strong beer segment was growing faster than mild beers. Having learnt its lesson, AB InBev launched Budweiser Magnum exclusively for India in 2012 with 6.2% ABV (alcohol by volume). Sharma calls this AB InBev’s aloo-tikki-burger moment. Since the launch of Magnum, AB InBev’s standalone market share has become respectable and the company claims that Budweiser has 50% of the Indian premium market. Mayank Bhatt, business head of pub chain Social, says, “Budweiser has nailed the balance between brand appeal and good taste. The flavour is widely liked and the brew is consistent.” Despite having lower ABV at 6.2% compared with Kingfisher Strong and Tuborg’s 7-8%, Budweiser Magnum contributes around 25% of the revenue for the Budweiser brand.

India moved up the ranks at AB InBev only after the SABMiller buy, where the intent clearly was to get a foothold in ‘growth potential’ markets in Asia and Africa. The SABMiller buy gave it a wider presence (11 owned breweries and two contract breweries in comparison to AB InBev’s one company-owned and one contract brewery) and portfolio in India but not much seems to have come out of it. Brand managers at AB InBev India are dealing with a problem of plenty, which has led to the neglect of SABMiller brands. “We do disproportionately focus and invest more in Budweiser. We by choice had decided on this strategy pre-integration with SABMiller. However, post integration, we got a portfolio which straddled across multiple price points and had a countrywide presence,” says Sharma.

The 2018 Euromonitor figures show a major decline in SABMiller’s market share, from 27% in 2013 and around 20% in 2016. A consumer goods analyst with a leading domestic brokerage says that Haywards once dominated the strong beer market with 30% share but now that has come down to 8%. “It failed to retain its appeal,” he says. While Haywards and Knock Out are hanging in there, the Euromonitor data does not even list Foster’s, a brand which once used to command 6% market share in the premium segment. Kingfisher has been more successful in this category by associating with events such as Sunburn and Octoberfest (See: King of strong). AB InBev also spends a big chunk on music and sporting events but all its spending has been focused on Budweiser than the other brands in its India portfolio.

The 2018 Euromonitor figures show a major decline in SABMiller’s market share, from 27% in 2013 and around 20% in 2016. A consumer goods analyst with a leading domestic brokerage says that Haywards once dominated the strong beer market with 30% share but now that has come down to 8%. “It failed to retain its appeal,” he says. While Haywards and Knock Out are hanging in there, the Euromonitor data does not even list Foster’s, a brand which once used to command 6% market share in the premium segment. Kingfisher has been more successful in this category by associating with events such as Sunburn and Octoberfest (See: King of strong). AB InBev also spends a big chunk on music and sporting events but all its spending has been focused on Budweiser than the other brands in its India portfolio.

The revenue contribution of SABMiller brands has also reduced from 80-90% in 2016 to 55-60% currently and market share gains by Budweiser and Corona are being offset due to losses in other categories. “AB InBev and SABMiller combined is still losing market share, although we don’t have the latest numbers available, we still believe that they have continued to lose at the net profit level,” points out the earlier mentioned FMCG analyst. Data from Ace Equity points to gross sales moving down from Rs.39.22 billion in 2016 to Rs.30.42 billion in 2018. However, according to the company, revenue for 2018 is upwards of Rs.40 billion as that Rs.30.42 billion does not take into account financials of a few private entities. In comparison, Carlsberg India closed 2019 with revenue of Rs.50.66 billion and net profit of Rs.1.29 billion. What explains Carlsberg’s success? “Out of seven breweries in the initial phase, Carlsberg had planted six of them in non-traditional markets, which had only Kingfisher and a few local brands. While SABMiller wasn’t aggressive about expanding into those markets, Carlsberg managed to establish a better presence. Eventually, through Tuborg it was able to break the market domination of Kingfisher and Haywards,” explains the FMCG analyst.

It may be hard to believe after a pub crawl on any Friday night, but beer is not even a favourite in this country where most drink to get a ‘kick’ with the underlying principle being cheaper the better. That is why quoting per capita numbers and then comparing it to a global average can be misleading. For a country like India with vast income disparity, per capita numbers many a time understate consumption and overstate market potential. Sample this, India’s per capita consumption of beer is stated to be 2.5 litres per annum compared with the average of the top 20 beer-drinking countries at 90.63 litres per annum. Go figure. That does not dampen Sharma’s enthusiasm though. “The entire quantity of beer brewed in India across brands, is just Budweiser in China. We have not even scratched the surface of this crowd, which has a great desire to connect with the world through products that don’t get them drunk an hour into the evening,” he says.

Rent seekers

Among AB InBev’s biggest roadblocks happen to be arbitrary taxation and alcohol policies, which differ from state to state. “For some states such as Telangana, the taxes can go as high as 70-75% of the MRP while for Rajasthan it is almost 85%. So we reinvest in states which can give us better margins,” says Sharma, adding that their top markets are Maharashtra, Karnataka and Telangana. According to a Motilal Oswal Financial Services report from 2016, revenue contribution through taxes for some states can go up to 40%. “A 330 ml Kingfisher premium lager which costs Rs.36 in Goa, costs Rs.150 in Himachal Pradesh,” laments Singh. States charge alcoholic drinks by volume and not alcohol concentration. Thus, a beer with ABV of 4.8% will be levied the same tax as rum or gin with 40% ABV. Given the liquor business’ cash cow status, the states are unlikely to reduce their vice-like grip. As it is, they are cash strapped after the rollout of GST and, since alcohol has been conveniently kept out of GST, the state governments might increase levies to compensate for any revenue loss under the new tax regime.

Not that after having its fill, the state is content to let sleeping dogs lie. AB InBev was recently banned in Delhi after charges of tax evasion on SABMiller brands. At first the ban was for three years, then it was reduced to 18 months and then, in early February, the city tribunal stayed the ban while continuing to hear the company’s appeal. Sharma, without quantifying the losses incurred by the company during this period, shares that it was a “significant” amount. Earlier, in October 2019, AB InBev had complained to the Competition Commission of India that an industry cartel was at play. It alleged that it included people from its Indian operations (acquired through SABMiller), and staffers at UB and Carlsberg. Amid the ongoing CCI probe, Carlsberg itself has launched an internal investigation at its India unit.

Who stole my fizz?

As if regulatory overkill wasn’t enough, beer majors have also to deal with lack of growth. This in a supposedly recession-proof business is puzzling. Euromonitor says the sale of beer in India by volume stood at 2,426 million litres in 2018 and is projected to be around 2,600 million litres in 2019. That is a growth of 7% in a market where most players were penciling in 15%, annually. If news reports are to be believed, 2019 barely seems to have seen any volume growth. 2017 wasn’t any better either. According to Euromonitor, “Total volume sales of beer were stagnant in 2017, mainly impacted by the highway ban and the lingering effects of demonetisation, coupled with some excise duty hikes. Consequently, these effects started to wane at the beginning of 2018, with the category witnessing growth, partly due to the low base of 2017.”

To get growth back, beer companies are trying out everything – premium, super premium, non alcohol, wheat beer; you name it. Meanwhile AB InBev’s competitors don’t want to miss any of the action and are getting equally aggressive. Just before Beck’s Ice was launched in 2018, Heineken brought in Dutch beer Amstel. Of the newer brands launched in recent years, most have been in the premium category. Bhatt says, in their restaurants, “While Budweiser and Kingfisher Ultra do really well, imported beers, Corona and Hoegaarden, are clear favourites.” To tap the microbrewery trend, AB InBev has partnered with Indian Hotels Company. The beer major plans to open 15 premium microbreweries at Taj properties across India in the next five years. In November 2019, it also launched its newest vertical 7 Rivers Brewing Co., which caters to the growing popularity of wheat beers. Its two variants Veere and Machaa are inspired by the traditional Belgium witbier and German hefeweizen respectively. “These are the first two of variants of a larger portfolio we will be launching,” says Sharma. UB, too, has launched its wheat beer under Kingfisher Ultra Witbier. “The bigger players are just trying to fill in any white space that they find so that they don’t miss out on any major trend,” says Pinakiranjan Mishra, partner and leader, consumer products and retail, EY India. The company also launched two non-alcoholic beers in India last year, Budweiser 0.0 and Hoegaarden 0.0, a move that enables them to sell through online channels and supermarkets.

Though India seems like a wobbly market, Sharma is optimistic. He says the increasing popularity of beer is making “the spirits guys” nervous. “I am celebrating it,” and adds that it drives him to innovate. The biggies are trying every variety to appeal to the young, even gluten-free beer, but microbreweries backed by venture funds aren’t far behind. Bhatt explains, “With our pan-India presence, we have observed varying trends in beer drinking in different regions. Our customers in the South lean towards craft beer given the presence of some of the country’s finest microbreweries in the area. The North and West regions are all about big branded lagers with the exception of Gurugram, again, because of the presence of microbreweries in the vicinity.” AB InBev India might finally be choosing its spots right but it is now running into more competitors than it bargained for.