“I realised within the first two to three years of my career that I wanted to move out of the country,” says Anand Sundaram, a UK-based IT professional, matter-of-factly.

Hailing from Kolkata, 54-year-old Sundaram has been working in the sector for almost three decades. But right after spending the first five years of his career in India, he knew he had to move. “There was no work-life balance. We had to wait for the boss to go home and could leave only after that. My interests were not getting fulfilled,” adds Sundaram, who moonlights as a classical musician and loves playing the guitar in his spare time.

His work took him to countries like Singapore, Russia, the USA and finally the UK, a country where he found what he was scouring. “There is no unnecessary wasting time here. If we are working from 9 to 5, we work. When we say work is over, it is over. I am not going to look at my laptop or phone every two hours to see if something has happened, and people respect that. That professionalism is missing in India,” the seasoned IT professional rues.

Why Indians Go Abroad

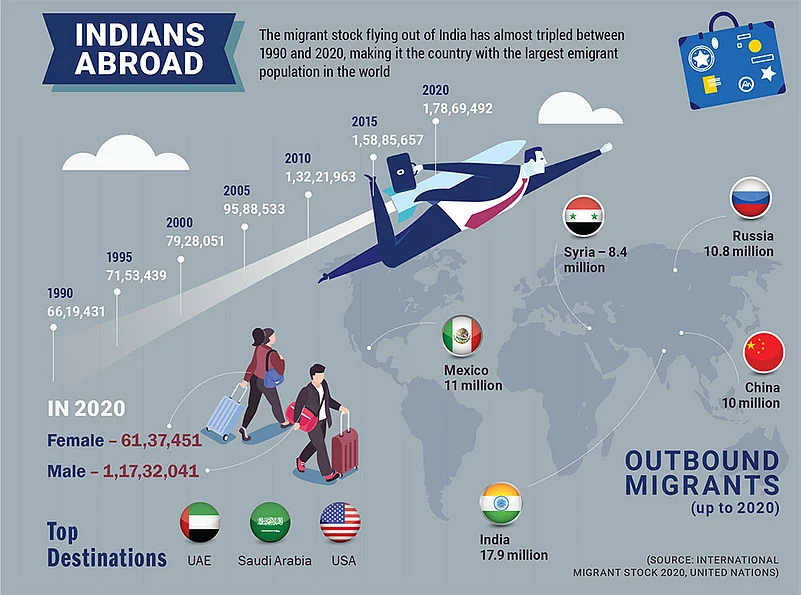

Like Sundaram, scores of Indian nationals, skilled and unskilled, leave the country in search of jobs and a better standard of living. The number has steadily increased over the years. According to the United Nations International Migrant Stock 2020, about 17.8 million Indians were living abroad in 2020, a number that stood at 6.6 million in 1990.

This migration generally happens towards developed countries that are trying to build a thriving knowledge economy, which depends on high skill levels to drive growth while also taking into account the productivity and development of its human capital. This, in turn, has driven many of those first-world countries to take active measures to ensure an optimal level of productivity by maintaining a fine work-life balance.

The latest country to join this cohort was Portugal. In November last year, the European country’s parliament passed a new set of labour laws under which an employer can be fined if they contact their employees after work hours. Countries like France, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Slovakia and Greece all have similar provisions—called right to disconnect—in place.

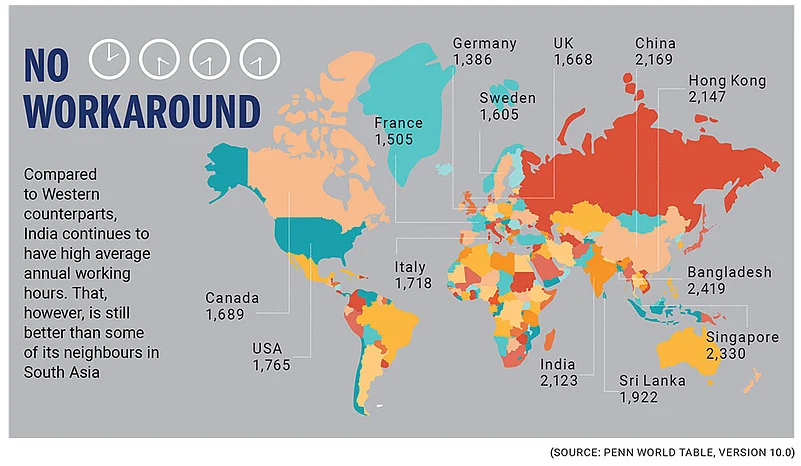

Interestingly, NCP MP Supriya Sule had introduced the Right to Disconnect Bill in the Lok Sabha during the 2019 winter session. The word of the big-ticket employers, however, still reigns supreme in the country. Employees are really scared to question anything over the threat of unemployment and salary cuts, says Anamitra Roy Chowdhury, assistant professor, Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University. “The number of work hours put in by Indians is one of the highest in the world. A part of the reason is even before the pandemic, the unemployment rate in India was the highest in 45 years. Since the pandemic, the market is not yet sturdy,” he explains.

He also points at the fact that many first-world countries also have social security and unemployment benefits, and if a person remains unemployed for a certain number of months, they get some kind of support. That is missing in India and other developing counties. “People simply do not have jobs. People say that let me first have a job, then I will think about work-life balance. Unless the overall labour market improves, it would be difficult [to address work-life balance question],” he says.

Changing Corporate Culture

The demand for a decent work-life balance, however, has picked up over the past few years. With the pandemic and work from home blurring the line between personal and professional, the need for that balance is more palpable than ever before. A study by Ranstad India confirms this idea.

Work-life balance, which stood at number two in 2019, topped the list of things that employees sought while looking for a job in 2021, surpassing even an attractive salary, revealed Ranstad’s REBR India 2021 report. Work-life balance scores the highest among females and those aged between 25 and 54, the report stated. Such was the recorded trend that the report went on to say, “It is therefore recommended that the average employer in India pays more attention to employee work-life balance to enhance their attractivity among prospective or current employees.”

Companies seem to be taking note of this suggestion. Krishna Raghavan, chief people officer, Flipkart, says that the e-commerce major ran a Coach with Compassion programme for people managers, where they are made aware of the signs of burnout and anxiety and advised on the role that they can play in helping people deal with stressful situations. To specifically deal with Covid-19, it allowed employees to take up to 28 calendar days of paid leave in case they were diagnosed with Covid-19 regardless of whether they were hospitalised or not. They could take unlimited bereavement leaves in case of the unfathomable loss of a family member.

On regular days, all its employees are encouraged to take breaks, including a mandatory one-hour lunch break when no other meetings can be scheduled. “They are supported in taking regular planned casual leaves to maintain a healthy work-life balance. Some teams have even declared mandatory days off every month and others are scheduling shorter working Fridays,” Raghavan adds.

IT major Wipro has an interesting policy that lets employees take sabbatical leave up to two years to work towards aspirations for self-development through higher education or take a break from work for up to 90 days to pursue a passion, hobby or contribute to a cause they believe in. The multinational conglomerate says that these practices foster the culture of innovation by nurturing intellectual capital of its employees. It also has a slew of women-centric programmes with an aim to create a level-playing field. “We have a programme called ‘Begin Again’, which is a second career programme for women who are seeking to restart their career after a break. The initiative enables talented women to explore career opportunities that can harness their potential and allow them to get back on track with the demands of the industry,” says Saurabh Govil, CHRO, Wipro Limited. Tech giant Google also follows the approach of helping employees obtain knowledge and skills in their areas of expertise or personal development. “We ask them to participate in an education reimbursement programme that offers eligible employees $12,000 annually to participate in personal or business-critical courses to improve a skill outside of what Google offers directly, for example learning a new language or attending personal development courses,” says Namrata Pareek Uberoi, benefits manager, Google APAC.

Covid-19 has changed the way Google works globally, making it more flexible from the employee’s point of view. Uberoi adds, “We see Google’s future workplace as a hybrid environment, where Googlers would spend approximately three days in the office and two days wherever they work best. Employees currently have the opportunity to temporarily work from a location other than their main office for up to four weeks per year.” Wipro, too, inroduced several new initiatives once the pandemic struck. Apart from switching to work from home, it focused on employee communication and wellbeing initiatives amongst a host of other policy decisions. But despite the efforts, the IT major faced difficulties in retaining talent. “While we continue to focus on employee support, flexibility and building world class talent pool, last few quarters have been challenging for talent retention and attrition has increased across the industry. To handle this, we have identified high churn groups and have rolled out focused initiatives around career, rewards and social capital to name a few. Additionally, we are taking steps to ensure that supply would not be a constraint for demand requirement,” Govil says.

Models of Happiness

To increase efficiency and productivity, a number of developed countries have toyed with the idea of a truncated work schedule. Finland had introduced a four-day work week in 2020. Trials for a similar idea in Iceland were a success. Sweden has been experimenting with six-hour days for a while now. Multiple private companies across the globe, including big names like Microsoft, Amazon, Google and KPMG, have put similar things to test over the past few years. Some companies have taken the global cues to India. Thursday became the new Friday for employees of Beroe Inc, a SaaS-based company with offices in Chennai and Bengaluru, when it started exploring the idea for Indian employees two years back.

For fintech company Zerodha’s founder Nithin Kamath, balance starts at work itself. “Good work-life balance starts with creating a decent environment at work, because most people end up spending most of their lives working. Instead of focusing on if it should be a four-day work week, the whole idea should be to make work a little less painful,” he says.

Kamath has been a loud proponent of creating that balance and had even voiced his opinions on Twitter about switching off and multitasking leading to bad performance. In fact, in the thick of the pandemic, Zerodha asked its employees to kill all synchronous (team/group) chats and conversations related to work by 6 pm every day. “Let us say that I ping someone on the group at 8 pm, everyone is forced to respond because I am the boss. When you know that you could potentially get a ping from your boss, you are constantly wired and thinking about work.”

One of the major reasons why most people in Zerodha’s core team have stuck around is for the work culture it has created and that the company cares for its people, he says. “People who stick around for high salaries move around for higher salaries. Money can never get people to stick around for too long. In the last few years, ESOPs have taken a lot of value, but for the majority of our life, we were not the best paymasters,” says Kamath.

Kaustav Dey, a senior research director at consulting firm Gartner, says that the world is transitioning from work-life balance to work-life harmonisation, where everyone is beginning to understand that the activities that you do outside work are important for work itself. “The pandemic has shown that we have generated a lot of synchronous work which is not needed—a lot of meetings and huddles that are not required. I have worked enough in Europe to know that nobody gives you a work phone call over the weekend, because it is an understanding that people have, because the weekend is for doing asynchronous work (work done alone),’’ he says.

Dey adds that this understanding is low in countries like India, Singapore and Malaysia. The concept here still is that if you are an employee, I own your time. “It has also sent out wrong expectations to the clients who gives jobs to India. They are used to the fact that Indian workers are like magicians—you give them work on a Friday evening, by Monday morning it is done,” he says.

Legal Route

India has been flirting with the idea of a four-day work week under the new labour codes, which are proposed by the Central government. Though no official announcements have been made on the issue, sources suggest that the government intends to change the work culture in the country with four-day-a-week option and restructuring of wages. However, here is the catch—it means that to stick to the older norm of a 48-hour week, the daily work hours shoot up to 12, which goes against the eight hours proposed in Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020, passed by the Parliament. This has left a cloud of ambiguity hovering around the eventual implementation of the rule.

But, then, who needs to step up first to ensure the right balance is maintained, the government or the corporates? Roy Chowdhury is of the opinion that unless the government clearly tells corporates what the codes recommend on minimum wages and working hours, better work conditions may not evolve. “Corporate social responsibility by itself is not going to bring in all these things. Some corporates might do it to retain workers, but if you want change on an economy-wide scale, that is not going to happen voluntarily,” he adds.

Gartner’s Dey maintains that the legal aspect always trails behind, and legislation will never give employees something that is ahead of what businesses want. He gives the examples of pension schemes and maternity benefits. The latter, he says, came about because big players in the market, like Unilever, P&G and Marico, had already made these changes in their human resource policies and had a head start of about two-and-a-half years. Then the government followed up. “I had not thought that the maternity laws would change so quickly ... When these companies started giving six months of maternity benefits, the government passed a law saying everybody has to follow that. Now, if you look at it globally, it looks better than most other countries in the world,” explains Dey while talking about the Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, 2017.

“Even in case of building a knowledge economy with an eye on productivity and work-life balance, the moment we see the Infosys, Wipro, TCS and Mahindras of the world changing their own company practices because they make it more attractive for others to join the company, the government can easily come up with a legislation,” he adds.

The government has realised that needs and expectations of a knowledge worker are different from that of an industrial worker. However, even to initiate a competition with other knowledge economies, where the knowledge worker is wooed aggressively, both the government and corporates need to take synchronous steps.

***

Disconnecting The Boss

In corporate culture, the “right to disconnect” has emerged as a new employee-friendly mantra, which is meant to keep the worker content and motivated. The idea has in fact become important enough for governments to start intervening.

Parliamentary Approval

In 2019, Nationalist Congress Party MP Supriya Sule introduced the Right to Disconnect Bill, 2018, in the Lok Sabha that sought to “recognise right to disconnect as a way to reduce stress and ease tension between an employees’ personal and professional life”.

Legal Definition

The bill seeks to define “right to disconnect” by stating that while the employer may contact the worker either through telecom, videocall, message, email or in other form of communication after work hours, the employee is not obliged to reply.

- An employee can go off communication system beyond work hours or during holidays

- Terms of disengagement between the employee and the employer to be mutually agree

- No disciplinary action allowed against the employee if they refuse communication from the employer

- Employer to pay penalty at the rate of 1% of the employee’s remuneration for non-adherence to any of the provisions

- Rules to apply in both physical office and work-from-home scenarios

- Every company to have an Employee Welfare Committee

- Digital detox centres to be set up for employees

- Ministries to have an oversight panel