On a sultry summer day in April, the kind that saps all your energy, I walk down a flight of spiral staircase that takes me 22 metres below Bengaluru’s MG Road to the spot where the Bengaluru Metro Rail Corporation (BMRCL), through Larsen & Toubro (L&T), is carrying out its tunnel construction for the underground section of a line, set to run between Gottigere and Nagawara, at full steam. Amidst the cacophony of machines and enveloped in heat and grime is 25-year-old Pallabi Modak, busy at work. Perched atop a four-metre-tall gantry crane, Modak can be spotted noting down the survey coordinates from the navigation instruments fixed on the tunnel’s ceiling.

“The alignment has to be 100% correct, as it is needed to maintain the alignment of the tunnel boring machine. Be it heat, humidity or rain, and it does not matter if the crane is full of grease, which it always is, you just cannot get the alignment wrong. It is crucial,” explains Modak, one of the first few women that L&T has posted as surveying frontline supervisors at the critical BMRCL project.

Just a few metres away from Modak’s crane stands Nandita Chakraborty, minutely observing every detail of the ring-building exercise inside the tunnel. Chakraborty is the only female quality assurance and quality control senior manager from L&T to be posted at the site. After the project concludes, it will be Chakraborty’s responsibility to hand over the site to BMRCL, making her the one who will be held accountable for any lapse.

Then there is 21-year-old Priyankari Biswas from Berhampore in West Bengal’s Murshidabad who never imagined that she would be part of a metro project in south India someday. “It is my first time outside home and I am thrilled. There is so much to learn,” she says.

Until a few years ago, the idea of a Pallabi, a Nandita or a Priyankari sweating it out in a tunnel alongside men would have been unthinkable. However, it is those very women who are changing the gendered idea of jobs and careers.

Preeti Hembrom operating a HEMM. Photograph: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan

Odd Woman Out

When Chakraborty joined L&T in 2007, she was the only woman working shoulder to shoulder with her 700 male colleagues. Fifteen years later, is it a different world today? “Of course, things have not changed drastically, but, as compared to those times, there are more women who are out in the field,” says Chakraborty, who opted for on-site posting at L&T right after completing her civil engineering degree.

Chakraborty, who lost her father at the age of seven, was raised by her mother whose strength, determination and go-getter attitude she has imbibed. “I was always this rough-and-tough person—assertive and focused. I have fainted, had my clothes torn and suffered injuries, but I know it is part and parcel of on-site jobs. If it were not for L&T, I would have opted for the police or army,” she says.

But in such male-dominated segments, did she not feel uncomfortable in terms of fighting off the male gaze? Interestingly, the women we spoke to did not recall any such uncomfortable “staring-down” incidents. “Even when I was a junior and the only woman around, I never felt that I was being stared at, maybe because L&T has such strict policies in place. The men knew they were being watched,” recalls Nandita. Pallavi, too, agrees. “If I was uncomfortable, I would not have continued working in this field. Plus, the company also takes steps, such as when there is a power outage and the tunnels are completely dark, men are asked immediately to move out.”

“We are increasingly witnessing a trend now where more and more women are opting for non-stereotyped careers, which traditionally used to be male-dominated. As a responsible conglomerate, we just play a catalytic role by hiring the right talent, keeping our women employees motivated like any other employee, building robust safety systems, training them regularly and offering an equal opportunity that their counterparts enjoy,” explains C. Jayakumar, executive vice president and head, corporate human resources, L&T.

Priyankari Biswas, a frontline surveying supervisor with L&T, at the under-construction site of a metro tunnel in Bengaluru. Photograph: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan

At STL cable factory in Silvassa, for the longest time, the colouring section of the plant—in which optical fibres are coloured in machines for better identification and differentiation—was exclusively managed by men. It was only in 2018 that the firm decided to hand over the reins of the section to women. Today, the plant boasts of 45 female machine operators, including a cohort of 15 young female engineers who joined with nothing but a diploma and an ambition to work in the manufacturing unit.

In the family of 23-year-old Sonali Sonu, she is the first woman to ever join the workforce. After watching her father battle with depression for years, Sonu knew she had to take care of her family and her two younger siblings who were yet to finish their education. “Seeing my father’s health, I realised that someone will have to take up that role,” says Sonu. This determination pushed her to pursue a diploma in electronic communications and eventually led her to STL.

For Sangeeta Patel from Varanasi, the job at STL meant an escape from marriage, clearing her family’s loans and pursuing a bachelor of technology degree. “In a family of six, my father was the only earning member. We would take loans for everything—from studies to illness—and I did not like it,” she says, breaking down while speaking over a video call from STL’s Rakholi office.

Both Sonu and Patel operate machines at STL’s Silvassa plant and have been promoted to the position of supervisors. “All of us work in shifts, including night shifts. Earlier, neighbours and relatives used to frown upon our jobs. Slowly, they understood our work,” says Sonu.

Ever since the Ministry of Labour and Employment lifted the ban on employing women in underground coal mines in 2019, the field is abuzz with interesting developments. Chandrani Prasad Verma, India’s first woman mining engineer, has carved a path for young women like Preeti Hembrom and Priya Mishra to follow into a space that was considered to be that of a man’s.

When Tata Steel launched its programme Women@mines, Hembrom and Mishra’s parents encouraged them to join it, making them the first women in their families, even home towns, to work in mines. After completing a one-year training course, the women are now employed as operators of heavy earth-moving machineries at the Noamundi iron mines in Jharkhand. While Hembrom works as a shovel operator, which excavates material and loads it on the dumper, Mishra performs underground drilling.

“I’d never even ridden a bicycle. Today, I am operating such a big machine. It is a combination of physical and mental work and I thoroughly enjoy it. My mother really encouraged me to join. Many girls in my colony ask me what is the procedure to work in mines. I am glad that I can inspire other young women to take up different kinds of opportunities,” says 25-year-old Hembrom, whose father and grandfather have also worked in mines.

In Mishra’s case, it was her father who informed her about the vacancy. She applied, cleared the written exam and then the interview. “Going underground and operating heavy machinery is not easy for anyone—be it a man or a woman. When I work, I am not conscious about my gender,” she expounds.

Beyond Tokenism

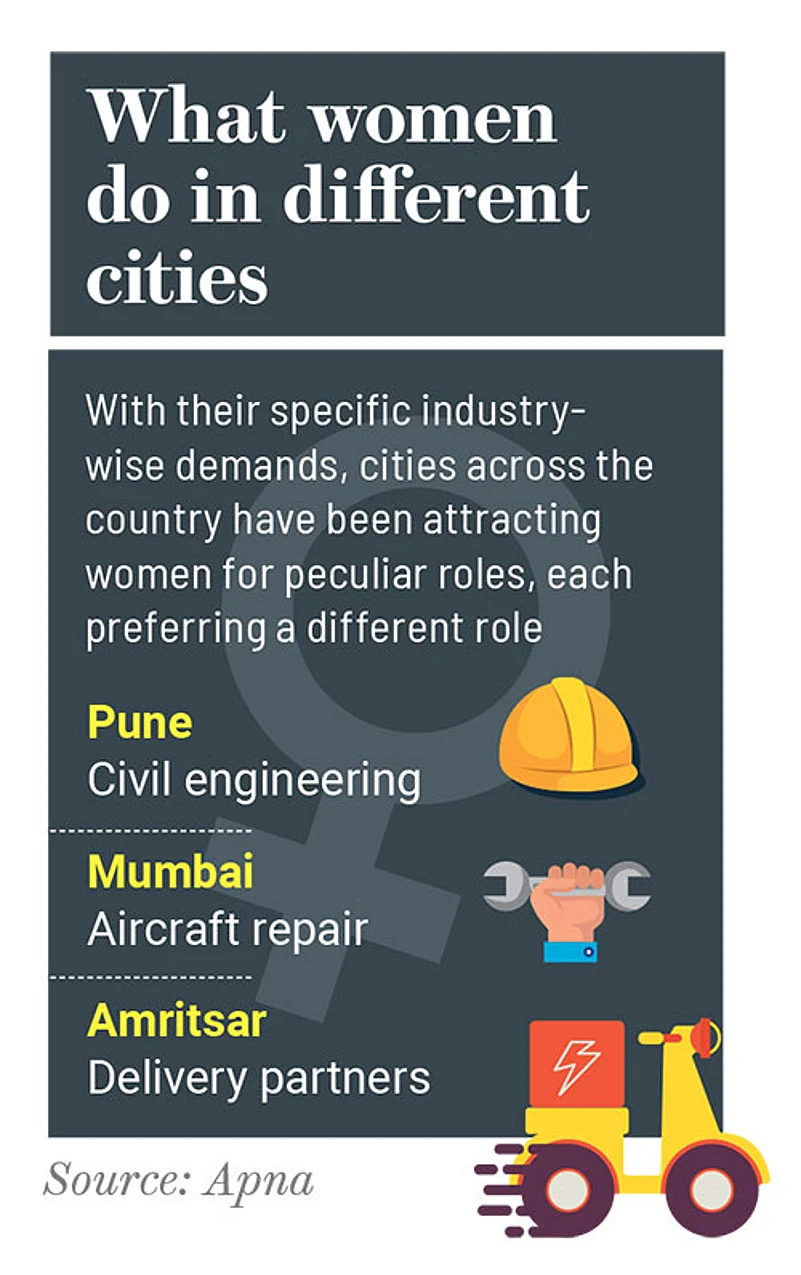

As women professionals slowly, but steadily, make their way past the male bastion, they are proving that there is nothing called “a man’s job”. This wave is not restricted to women’s ambitions alone. Employers have also been increasingly hiring women in unconventional roles, such as drivers, security guards, delivery partners, fitness trainers and peons among others, found job search platform Apna in 2021.

“Initiatives taken by the government, like Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan and upskilling programmes by the National Skill Development Corporation, are commendable in this regard,” says Karna Chokshi, chief operating officer, Apna.

It is also about diversity and inclusion with multiple organisations across the globe and India making efforts to incorporate D&I. But the question arises—why should they do it? Is there anything in it for them? While most see D&I as a social concern, data proves that organisations that embrace D&I actually end up improving productivity and profits.

The Boston Consulting Group, for example, conducted a study suggesting that companies having diverse management teams recorded 19% higher revenue.

Women taking up roles once believed to be reserved for men is one step towards achieving D&I goals. “More and more women are taking up unconventional roles and upskilling through activities, such as learning to drive dumpers, drilling holes for blasting, and, thereby, standing strong as the backbone of the workforce,” says Chokshi.

The corporate world is taking several initiatives towards D&I.

On the occasion of International Women’s Day on March 8 this year, JSW Steel set up a women-run cut-to-length unit, which makes sure that the steel coils are uncoiled, flattened and cut to length at its plant in Karnataka’s Vijayanagara. The line, which deploys major equipment like an uncoiler, a straightener, brushing machine, trimmer, leveler, flying shear and stacker, is managed by the team of 61 women working across three shifts.

Last year, Ola announced that its two-wheeler plant in Tamil Nadu will be run entirely by women. Mahindra & Mahindra has also hired 150 women for its automotive and farm equipment manufacturing facility. The company set up its first all-women automobile service workshop in Jaipur in 2019.

Anjali Byce, chief human resources officer, STL, feels that hiring women also makes for a strong business case. “When you put people from diverse genders, ethnicities and geographies together, you get efficiency and innovation as by-products. Also, if 50% of the world is men and 50% is women, it would be very naive of us to create something without considering ... [women] as potential consumers,” she says.

Riding high on confidence, family support and gainful atmosphere at work, women are now embarking on new journeys, breaking one stereotype at a time.

***

Smart, Fiesty Women Of Mobile World

On most mornings, one can spot thousands of women workers streaming into the electronics manufacturing cluster at Andhra Pradesh’s Sri City, which houses companies engaged in electronic R&D, design, manufacturing and assembly operations. Similarly, scores of women work in mobile manufacturing plants in Tamil Nadu. These women, who check batteries, look for defects and test audio, are employed in large numbers by these plants to assemble phones. Foxconn, which manufactures smartphones for various brands, has women making up over 95% of its total staff in its assembly lines.

In India, women form a significant part of the workforce that is engaged in electronics manufacturing. The reason behind that is there are several parts of the process that women excel at. Scope soldering or joining the electronic components in devices, for instance. Done under a magnifier, the process requires not only focus but also impeccable hand-eye coordination—something that women excel in. While the manufacturing companies hire them for their high level of commitment, focus and dexterity, many of these women, who come from the underprivileged backgrounds, are happy to land respectable jobs and a source of income to clear their debts and run households.

Having said that, their journeys are riddled with challenges related to working conditions. Last year, women workers from Foxconn’s Chennai plant staged protests over 250 staffers falling ill after consuming food served in the dorms. The workers also complained of unhygienic conditions at the plant, which was forced to shut down temporarily following the protests.