At a time when sustainability has graduated from being a buzzword—even a fashion statement for many—to becoming a serious concern for the planet, the fashion industry is guilty of many sins. It produces 10% of the total global CO2 emissions, or four to five billion tonnes annually, guzzles down 215 trillion litres of water, accounts for 20% of annual wastewater—the list is long and is set to get longer.

Sustainability is to maintain at least a status quo, and avoid any further depletion of natural resources in the context of climate action. But as it stands beyond individual posturing and activism, fashion falls fashionably short of meeting this definition. Sample this: According to United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the consumption of apparel world over is expected to rise from 62 million tonne in 2019 to 102 million tonne over the next decade, that is if the demographic and lifestyle patterns remained unchanged.

A 2016 McKinsey report titled Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula said that between 2000 and 2014, clothing production doubled and the number of garments purchased per capita increased by about 60%, attributing the rise to falling costs, streamlined operations and rising consumer spending. The report also said that in the five countries—Brazil, China, India, Mexico and Russia—apparel sale grew eight times faster than it did in countries like Canada, Germany, the UK and the US.

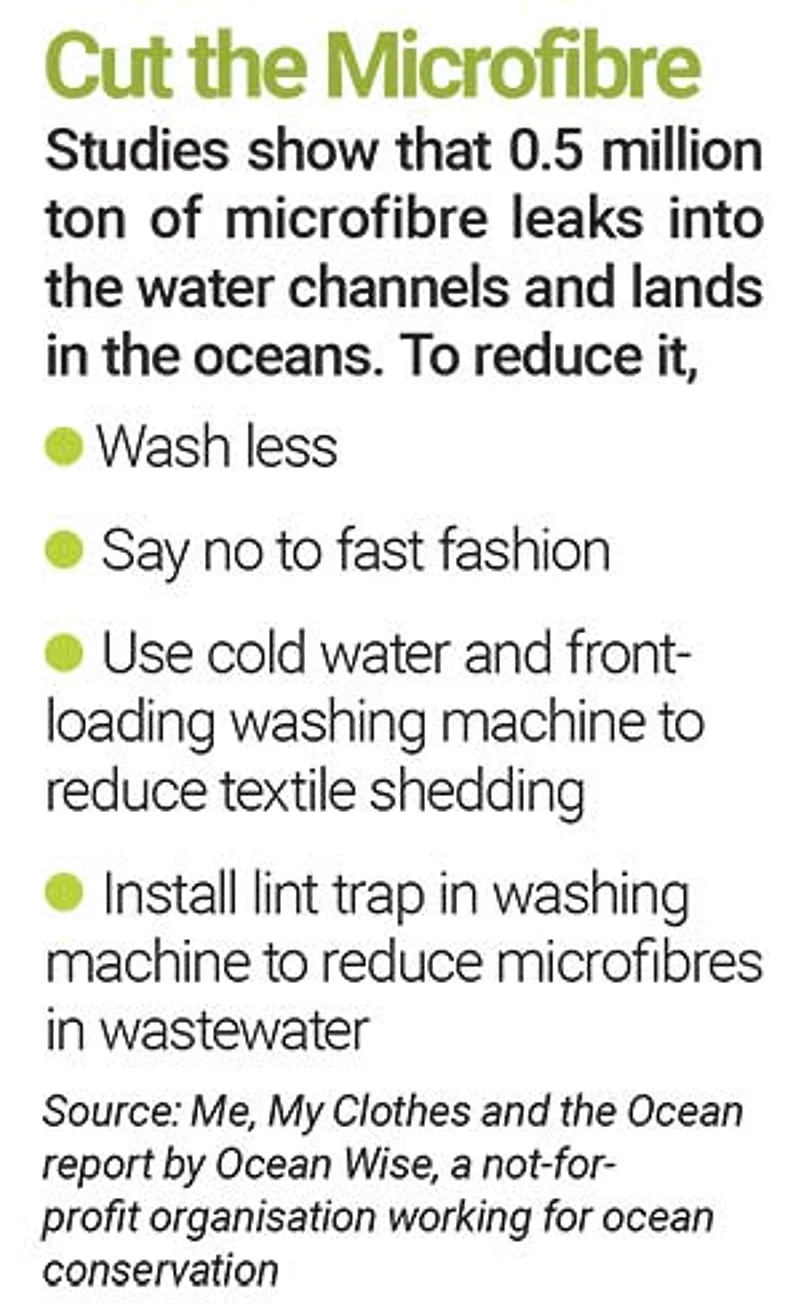

What is more concerning than the high production of clothes is where they end up after having run their course. A World Economic Forum report of 2015 stated that when clothes were discarded, 73% were burned or buried in the landfill. Around 12% clothes that went for recycling were likely to end up being shredded and used to stuff mattresses, or made into insulation or cleaning cloth, while less than 1% were used to make new clothing. Other factors to be taken into account were losses in production and during collection and processing as well as microfibre leakage.

Fast (and Furious) Fashion

While the fashion world and its proponents, the mighty brands, have started to weave sustainability into their agenda, a lot is still left to be desired. The trend of fast fashion, mass production of cheap and trendy clothes in huge volumes, has been a gamechanger for several global brands like Zara, H&M, Forever 21 and so on.

An Ellen MacArthur Foundation report found that 50 billion new garments were manufactured in 2000, a figure that doubled by 2019.

According to Kenneth P. Pucker, a senior lecturer at the Fletcher School, USA, fast fashion can be lucrative. “Put together, planned obsolescence, social media, technology and nimble supply chains contribute to sale of more stuff, which is the objective of traditional fashion firms,” says Pucker, who has authored articles on efficacy of sustainability, in an email interaction with Outlook Business. While the trend has been raking in the moolah for the brands in the $2.4 trillion industry, the impact that it has had and continues to have on the environment is a different story.

According to the UNEP, about 60% of synthetic fabric made into clothing, including polyester, acrylic and nylon textiles, is plastic. The report states that while they are lightweight, durable, affordable and flexible, “every time they are washed, they shed tiny plastic fibres called microfibres, a form of microplastics” that are as tiny as up to five millimetres in size and cannot be extracted from water. Every year, half a million tonne of plastic microfibres is dumped into the ocean, the equivalent of 50 billion plastic bottles, World Bank figures state.

Luring with the Green Label

Consumers today are highly educated, tech-savvy and aware of the practices carried out across the globe, says Varsha Jain, professor of marketing at MICA business school. “Their motives for buying fashion brands have changed; it is no more about just price but sustainability and eco-friendliness. Consumers want to purchase and consume fashion brands which can help the environment.”

“Fashion brands should thoroughly understand the importance of 3 Ps—people, planet and profit. Greenwashing does not help fashion brands in the long run,” she adds. Greenwashing, according to earth.org, refers to an organisation’s “deceitful advertising method to gain favour with consumers who choose to support businesses that care about bettering the planet”.

As per UNEP figures, it takes 3,781 litres of water to make a pair of jeans—from the production of the cotton to the delivery of the final product to the store—which is equal to the emission of approximately 33.4 kg of carbon equivalent.

Leading American denim jeans maker Levi Strauss & Co. claims that by using special techniques, it has been able to reduce freshwater use, adding that it has recycled over 11.5 billion litres between 2011 and 2021.

In 2013, clothing brand H&M rolled out its Garment Collecting programme under which, people can drop bags of old clothes at the nearest H&M store and get points which they can redeem while shopping at the store.

Zara, one of the biggest clothing brands globally, plans to use only organic or recycled raw materials for its clothing by 2025 and claims to follow the circular economy model to increase the lifecycle of its products.

US-based Patagonia too aims to be carbon-neutral by 2040. As per its website, the company increased its use of organic and recycled material across its product line from 43% in 2016 to 88% by 2022.

The Myth of Sustainable Fashion

“Less unsustainable is not sustainable,” Pucker has observed in his paper The Myth of Sustainable Fashion which was published in the Harvard Business Review last year. “Few industries tout their sustainability credentials more forcefully than the fashion industry... The sad truth, however, is that all this experimentation and supposed ‘innovation’ in the fashion industry over the past 25 years have failed to lessen its planetary impact,” he notes.

Be it clothes from sea waste, shoes without synthetic fibre, dresses made of organic cotton, fashionwear made of recycled material or manufactured in factories powered by solar energy, shopping malls and shelves are overflowing with items promoted by claims of “environment friendly” and “sustainable” manufacturing. However, pressures of growing demand and pricing points make fashion anything but sustainable.

While recycle, reuse and rent might have become fashionable words, they have little impact towards betterment of the planet. “Recycling is oversold... does little to limit environmental damage,” Pucker comments in his paper. On resale, he writes, “over the past 10 years, the average percentage of carbon emissions obviated due to resale amounts to far less than one hundredth of 1%.” His commentary on the fashion rental is equally grim. Rent the Runway, which pioneered fashion rental, has admitted that “rental only reduces CO2 by 3% versus conventional new apparel buying”, he writes.

Pucker tells Outlook Business that the biggest roadblock in the apparel world’s path to sustainability is the system in which companies operate. “The system structure and incentives reward growth, not planetary welfare. In situations where private profits and social welfare are aligned, sustainability will prevail. However, in most circumstances where private benefit and public welfare are in opposition, sustainability will lose out,” he says.

He is sceptical about the impact of the so-called sustainable measures by brands. “Corporate voluntary market-based action has been in process for a quarter century but even as the focus shifts from reporting to certification to win-win solutions, carbon emissions continue to grow, water becomes scarcer and fashion supply chains remain obtuse and extended,” he says.

For the world to meet its climate goals, every industry must do its bit. The apparel segment too must step up and bring in reforms with the genuine intention to make a difference. Until then, as Pucker observes, the industry will continue to advocate fanciful solutions that will defer regulation and the necessary substantive conversations and actions required to address an increasingly pressing situation.

With input from Naina Gautam