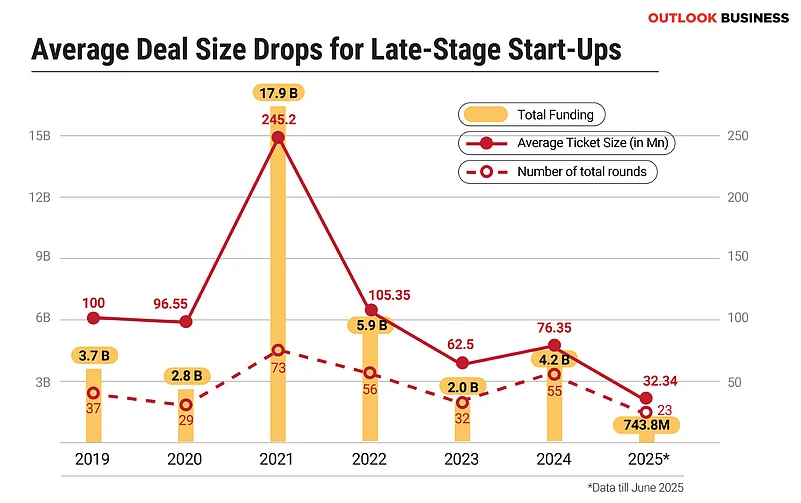

The era of mega funding deals is slowly fading for late-stage start-ups in India. The average ticket size has declined by nearly 25% in the past four years. In 2021, the median deal size soared to $245 million. However, the number dropped to $76 million in 2024 and $32 million in the first six months of 2025.

The total funding volumes also tell a similar story. It witnessed a significant drop from $17.9 billion in 2021 to $4.2 billion in 2024 and $743 million in the first half of 2025. An analysis of Tracxn data by Outlook Business reveals that the number of late-stage funding rounds has reduced by nearly 28%, i.e., from 73 in 2021 to 55 in 2024.

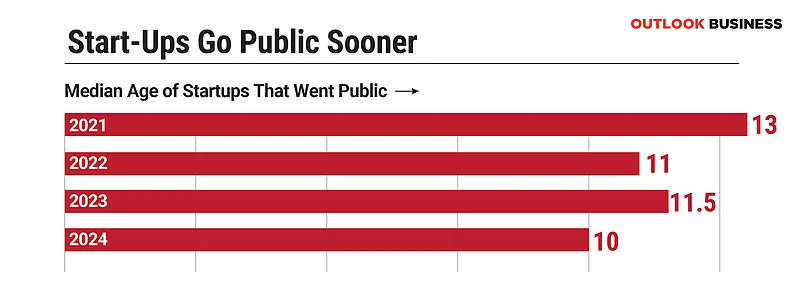

The data also stated that start-ups are now rushing for IPOs as the median age to go public has dropped from just 13 years in 2021 to 10 years in 2024. This twin trend has reshaped the start-up strategies, with industry experts calling it a “healthy” reset and public markets becoming a “real” option.

Inside Shrinking Big Ticket Sizes

The sharp decline in late-stage ticket sizes is a convergence of global macroeconomic tightening and a structural correction in how start-ups are valued and funded, according to Navin Honagudi, managing partner at Elev8 Venture Partners.

“In 2022, we saw exuberant funding driven by cheap liquidity, leading to inflated valuations and oversized rounds. But as interest rates climbed and LPs pulled back on commitments, capital became more cautious. Investors have pivoted from growth-at-all-costs to unit economics and profitability,” he says.

Another key driver is the recalibration of start-up valuations. Honagudi says that many late-stage companies that raised in 2021 at 25–30x revenue multiples are now facing the reality of 8–10x multiples or lower, which naturally reduces round sizes.

IPOs Mark Shift in Start-Up Strategy

Start-ups are increasingly viewing the IPO route as a “quasi-Series D” funding round because the public market offers liquidity, brand validation, and long-term capital, says Bhavik Joshi, Business Head, INVasset PMS. However, there is a difference in accountability.

Unlike Series D, where valuation conversations happen behind closed doors, IPO pricing is publicly scrutinised, he notes. For instance, Mamaearth had to revise its valuation expectations during its IPO process, which trimmed its pre-IPO premium.

On the other hand, travel platform Ixigo, with its near break-even numbers and operational leverage, proved better prepared than some of its peers. Start-ups like MobiKwik, meanwhile, have struggled to gain investor confidence despite brand recall.

Eklavya Gupta, CEO and cofounder of Recur Club, echoes similar sentiments, saying founders are thinking beyond private rounds and actively considering public markets as an option. He explains it well with the liquidity story in India.

There are 110 million new demat accounts in four years, and the daily cash turnover is now $15 billion. “These aren’t just numbers, they show that retail and domestic institutional capital can now fund growth stories at scale, which wasn’t true a few years back,” he says.

According to Gupta, IPOs are not just a funding milestone; they are a “permanent shift in how a start-up operates”. Unlike the Series D funding round, start-ups that go public are committed to quarterly predictability and governance standards.

However, Gopal Jain, cofounder and managing partner of Gaja Capital, does not see public markets as a substitute for later-stage capital. “This capital is an important bridge between the early stage and IPO and must bring more to the table than just funding. It is a critical phase where companies must build internal financial maturity to prepare for life post-listing,” he adds.

As per Rainmaker Group’s RainGauge Index FY25 annual data, venture capital-backed Indian start-ups rose over ₹44,000 crore (approximately $5.3 billion) in FY25 from public markets via IPOs, FPOs, and QIPs. The trend shows that public markets outpaced private capital for late-stage fundraising, solidifying their role as the dominant source of growth capital.

Going Public Is New Growth Metric

IPO launch is not actually the end game for start-ups. It rather requires governance structures, discipline, and consistency. After going public, start-ups listing on inflated expectations often face sharp drawdowns when growth slows or profitability remains elusive.

Joshi gives an example to back this trend. For example, Paytm and MobiKwik – both strong in user metrics but weak on bottom-line stability.

Additionally, Indian bourses also require quarterly disclosures, board independence, and internal controls that many young start-ups are unprepared for. And on top of this, retail investors often don’t understand the nuances of start-up metrics. When profitability is absent, the narrative must be airtight, he says.

“A failed IPO or post-listing decline can affect employee morale, vendor trust, and future capital raise. Indian investors are forgiving of slow growth, but not of opacity or capital misuse. Governance readiness is no longer a checkbox—it’s a core IPO metric. Companies that rush without building this muscle are not just risking their stock price; they’re risking their institutional reputation,” Joshi added.

Sandeep Murthy, managing director of Lightbox also says that rapid expansion without a credible route to surplus is "no longer tolerable". "Backers demand evidence that revenue and profitability are already sharing the same ledger".

Road Ahead for Indian Start-Ups

Despite the shift in trend, Honagudi believes that the late-stage cheque sizes will gradually bounce back, but are unlikely to return to the extremes of 2021. For the rebound to materialise, there should be fundamental shifts like a strategic M&A market with successful exits, rationalized valuations, stronger institutional LP participation, and more.

“If these things come together and India continues to deliver on its economic and digital growth story, we could see late-stage capital come back with greater discipline and depth by 2026–27,” he says.

Currently, start-ups with strong unit economics, low acquisition costs, and a demonstrable moat will thrive in this era. Joshi says that travel tech players like ixigo, fintechs with lending rails, and profitable D2C brands with lean supply chains can find investor appetite if they show a disciplined approach to capital and clear profitability timelines.

In addition, start-ups with deep integrations into India’s digital infrastructure—like ONDC-linked commerce platforms or B2B SaaS with strong recurring revenues—can command premium valuations, even if early-stage.

On the flip side, high-burn consumer apps, social media platforms with weak monetisation, and edtech firms reliant on aggressive discounting should avoid public markets unless their financials mature.

Hence, the IPO is no longer a marketing event—it’s a trust contract. Start-ups need to earn their listing, not just file for one.