There is the Buddhist story of a boy who turned a dead mouse into a fortune. He built his riches step-by-step, by imaginatively reusing every bit of trash he found. He successfully traded the rodent for honey, later dried twigs for pots and finally bundles of fresh grass for jewels. The last was bought by wealthy merchants looking to feed their tired horses. It is a long story but the moral is simple — everything can be mined for gold, if you can spot the vein.

DCM Shriram, the 120-year-old diversified conglomerate, has displayed similar ingenuity in mining gold from the various businesses in their basket — however boring and unglamorous they may be. The Shriram brothers — Ajay, Vikram and Ajit — who run the show now were handed down a troubled business after the partition of the legendary Delhi Cloth Mills founded by Lala Shri Ram in 1909 as a textiles company. They were once to Delhi what Tatas were to Mumbai, even opening institutions of excellence such as the Shri Ram College of Commerce (for higher education) and Shri Ram Centre for Performing Arts. Then, in 1990, the group was split into four among Lala Shriram’s sons and their heirs. DCM Shriram was born with the three grandsons inheriting Kota complex (with chlor-alkali and PVC units in Kota, Rajasthan) and the textile business in Delhi’s Moti Nagar.

Diversified businesses were the norm during the licence raj when there were constraints on capacity addition – the only way to expand a business was to find new business lines and/or form new companies with new capacities if the licenced capacity was breached. After the mid-nineties, diversified businesses went out of fashion as the market refused to fairly value conglomerates. That’s because investors no longer fancied buying a bunch of businesses with mixed fortunes, and modern management, too, advocated core competency as the way to go.

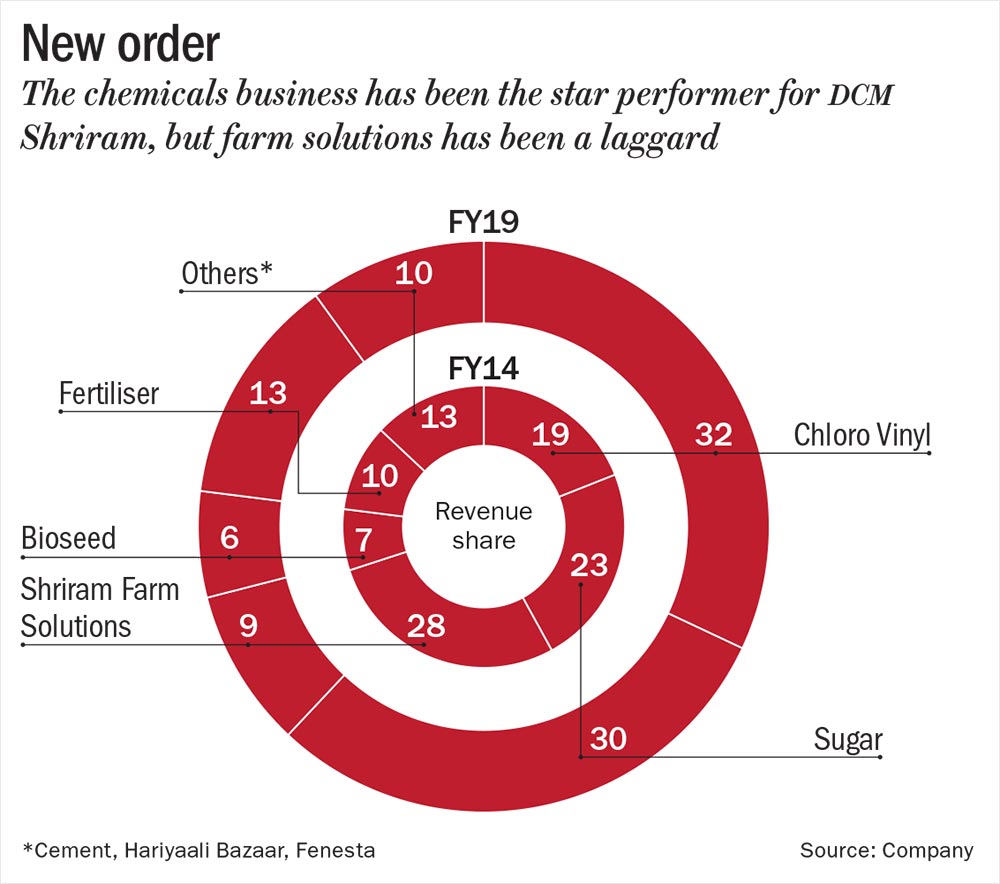

To cope, most business houses realigned their portfolios, spinning off different businesses as separate companies. The Delhi-headquartered group, however, has continued with its diversified portfolio till date with interests in chemicals, sugar and value-added products. Over the years though, they have pared down loss-making businesses — textiles and agri-retail, and ploughed money back into the rest of the pack, especially chemicals. The diversified business structure actually helps. “When something goes down, something else goes up. As a group, we are generating sufficient cash flow to reinvest and grow,” says Vikram (See: New order).

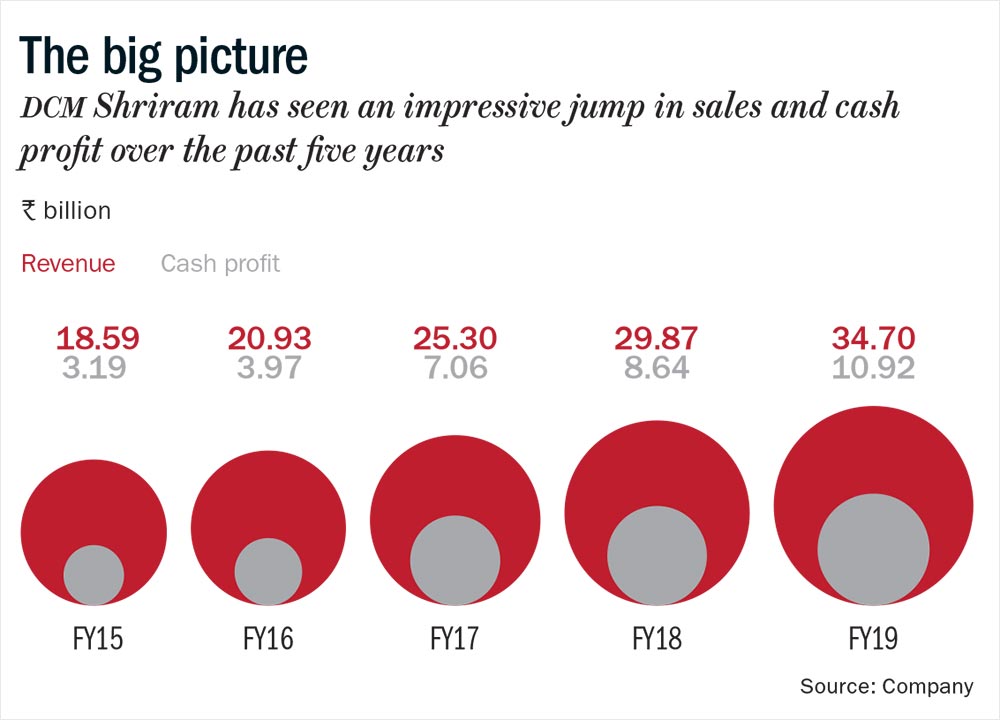

DCM’s three-pronged approach focusing on cost, building scale and integration has helped the company show impressive topline and bottomline growth. Over FY14-19, sales jumped from Rs.56 billion to Rs.77 billion, and more impressively, cash profit jumped 3x from Rs.3 billion to Rs.11 billion (See: The big picture). DCM Shriram’s free cash flow is driven by chemicals with a hefty contribution of 76%, and high margin of 39%. Needless to say, the chemical business, too, has been buoyant, helping the company grow. “The idea is to continuously set the ball rolling in a virtuous cycle of investing, increasing capability, integration and increasing margins,” says Vikram. Running a tight ship and scaling is the only way for a commodity business to run profitably, DCM’s integration strategy has helped in delivering better return than its peers.

Plus plus game

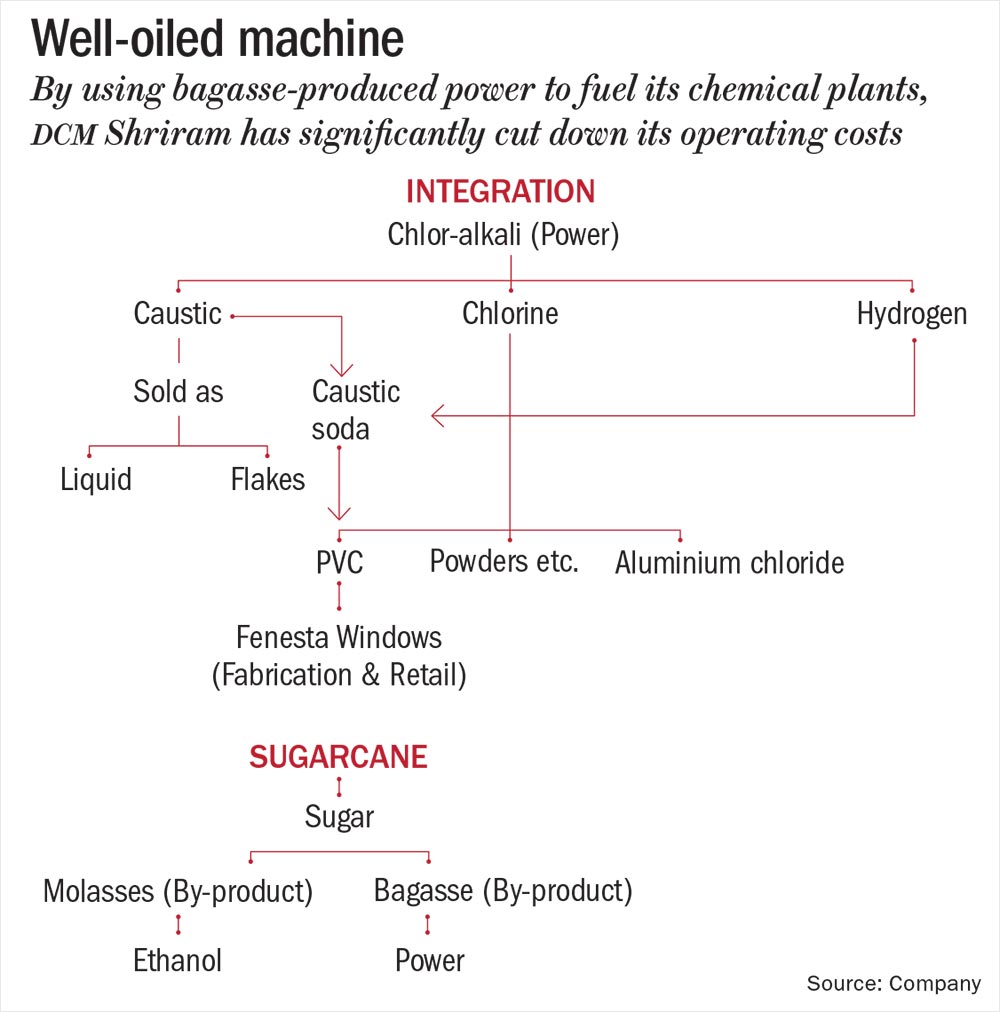

It’s in the chemicals business that you can see this ingenuity play out at its best. When its chlor-alkali unit generated caustic soda as a by-product, it used it to make PVC. The making of PVC generated a sludge, so they processed it to make cement. The PVC itself was used to manufacture windows under the Fenesta brand.

Integration is of two kinds — backwards integration is when a company produces raw material needed for a business vertical (such as generating power to run chemical plants) and forward integration is when it uses the by-product of a process to manufacture something else, such as using bagasse to produce power or using the sludge to make cement. DCM has integrated both ways (See: Well-oiled machine). The result: their overall profitability is better than that of competitors. In the chemicals business for example, DCM’s profit margin is higher than peers, Grasim’s and Gujarat Alkalies’, whose margins fall between 27% and 30%. Pratik Tholiya, who covers chemicals sector at Elara Capital says, “Those higher margins are a result of high level of backward integration. They probably go six levels downstream.”

To be fair, this strategy was partly handed down to the brothers in their chemicals business. The Kota complex in 1990s had captive power plants to manufacture chemicals, from which, two to three downstream products were made; the Bharuch plant replicated this integration. The PVC business led to Fenesta Windows that now contributes Rs.3.9 billion to the company’s kitty. This brand, retailed at 135 stores across the country, enjoys 20% market share in a Rs.20 billion market. “Although the real estate sector is down, we get 1,000 customers a month,” says Ajay.

The management’s ability to extend a by-product generated during the production of caustic soda solved a big headache for the company. This process generates chlorine, which is difficult to dispose. “For a tonne of caustic, you produce 0.88 tonnes of chlorine, and had to pay to get rid of it,” says Tholiya. The company creatively solved this problem. In 2018, they introduced a chlorine-based product called aluminium chloride by setting up a 60-tonnes/day plant for Rs.430 million. They are expecting to make Rs.1.1 billion in revenue in FY20 from this.

Amar Mourya, research analyst at Emkay Global believes that the company may have solved two of their problems — chlorine and dependence on sugar — over the past two years, through integration. “They have already come up with derivatives of chlorine and are likely to introduce a few more. They are also a sizeable sugar player. Due to vagaries of the sector, they took a very serious write-down two years ago. Now, with the changed government policies, they will make profit,” believes Mourya.

The policy that Mourya is referring to is the central government’s decision to increase the percentage of ethanol in fuel blends from 1.5% to 7.5%. This reduces mills’ dependence on sugar and cuts down its production, since molasses is diverted for the manufacturing of ethanol. The new policy also allows the mills to sell excess power generated from cane waste.

This policy change is right up DCM Shriram’s alley, of letting one business vertical lead to more revenue streams. The company has already invested Rs.1.88 billion in building new ethanol distilleries alongside its sugar mills and in increasing power generation capacity. Another distillery with an investment of Rs.3 billion is coming up in Q3FY20. Ajit says, “We believe ethanol consumption will increase further in India. Its consumption in Brazil and parts of US is 25% and, in the EU, it is 17%. Its use is a win-win for all since it is environment-friendly, cheaper than oil and you save forex,” he says.

DCM Shriram’s sugar vertical has generated a profit of Rs.1.91 billion from distilleries and power generation in FY19. Tholiya of Elara Capital says, “DCM never had any ethanol capacity, but they are building it. It is not cyclical but a quasi consumer play, which will give you higher margins. They are expected to generate sustainable cash flows from this.”

Ajit is also excited about the new National Biofuels Policy 2018 that promotes second generation refineries for ethanol. This allows farmers to use excess produce, and not just molasses, to make the biofuel. Waste can be turned to profit. “Going forward, we can use paddy straw, wheat straw and other waste materials. This smog that envelops Delhi during winter, when straw is burnt, will be resolved… the straw can be used in the future,” he says. According to the proposed policy, government will allow farmers to divert excess crop produce for biofuels production and set aside Rs.50 billion to help establish second-generation ethanol refineries.

But the sector woes are unlikely to end soon, according to Ajit. He says, “The government needs to link cane and sugar prices. This is a fundamental shift that needs to happen. 14 countries are already following this model.” DCM’s luck is tied to the state of market. There is still carry-over stock of seven months from sugar season 2018 with the millers. Production cost for sugar in FY19 is approximately Rs.3,300 per quintal, which meant a negative margin of nearly Rs.200 per quintal for Q4 FY19.

They are better off this year in sugar, because sugar volume has marginally increased, ethanol is a new source of revenue, and power revenue has also increased. Ancillary business has made sugar profitable for DCM Shriram. Annual net revenue for this segment is up 20% at Rs.23.53 billion, and sugar revenue is up 8%. Distillery operations, which started in January 2018, also reported a profit of Rs.1.47 billion in FY19.

Save and spend

Keeping a close watch on expenses is another one of this company’s winning strategies. The flagship Kota complex as well as the plant in Bharuch is a physical manifestation of their integration philosophy, with one unit feeding the other. It works (largely) as one machine and helps in being cost efficient.

“Majority of our businesses are commodity businesses, which bank on the international pricing of raw material and the final product. Therefore, we have to keep our focus on the cost of production, since it is crucial to remain competitive on a global scale.” The need to be cost-competitive is higher than than ever. “Ten years ago, duties on our products were 60-70%. Today, it’s zero. So, we have to compete effectively with global players,” he says.

In the chemicals business, they have cut down on one of their major expenses – power, which accounts for 60-70% of the running cost – by having captive power plants. They have around 250 MW captive power for two chemical plants, and long-term agreements for coal supply.

They have also upgraded technology to make power usage more efficient. “Five years ago, average power consumption in the alkali plant was around 2,650 units per tonne. Today, it is near 2,000 units per tonne. We are putting up a new power plant in FY21, which will reduce cost by 25%,” informs Vikram. Operating costs per tonne to selling price fell from 67% in FY16 to 47% in FY19. This relentless focus on costs and well-timed investments have helped the company earn steady cash flows and build a strong balance sheet.

Timely scale-up

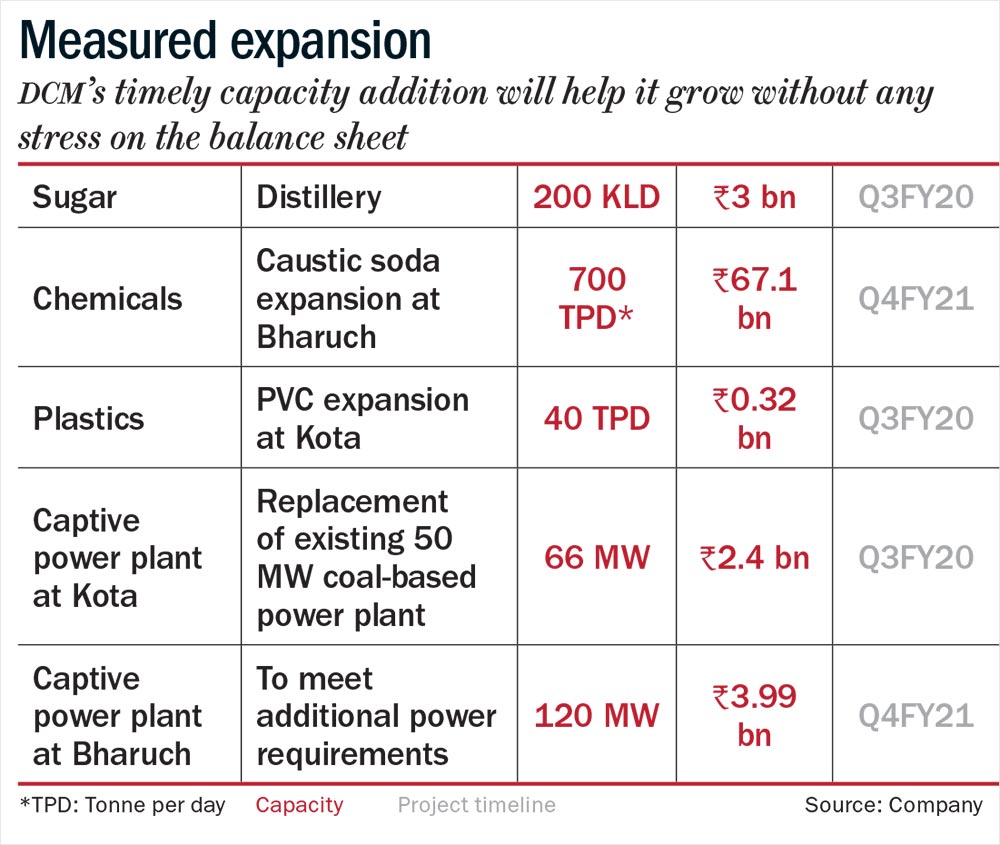

The cash cow continues to be the chemicals business throwing up Rs.3 to Rs.4 billion in cash every year. So far, the company has carefully caliberated its capacity expansion. Mourya says, “They are a balance-sheet focused company and have always been this way. They believe in the power of scaling up, but avoid taking undue financial risk.” (See: Measured expansion). That has also ensured they do not fall into a debt trap, the most common mistake commodity companies end up making. Vikram spells out their approach. “In terms of debt, what the market considers a comfortable level, we try to be well below that. We do things incrementally in phases. That’s how we have done it over the past five years, with half a dozen expansion for integration projects, reaping their benefit and then entering the next phase,” he says.

Financial discipline can make or break a commodity business. Mourya says, “Businesses end up before the bankruptcy court not because they don’t know the business, but they are often not able to prepare for and survive the bad cycles.”

Challenges ahead

While integration has largely worked for the company, it did see not-so-happy results as well. One was Hariyali Kisaan Bazaar, which it opened in 2002 for rural retail, as an extension to its agri-rural vertical. It did not take off. Its revenue did increase rapidly over a decade but never posted a profit, instead it registered a loss of Rs.1.06 billion. Finally, in FY13, it shut down retail and pared down the outlets, which now sell only fuel products.

Then, the Fenesta story is looking weak although one can’t write it off yet. Tholiya says, “It is heavily dependent on the realty sector, and Fenesta is not meant for mass market. It is a premium brand and not much activity is happening in this space.” Being a commodities-heavy company, they will have to make extra effort to be seen as a consumer-space player. Ajay says, “Ultimately, we are a supplier to a business. So, we work towards saving our customers money and being more efficient. Can we supply goods to him 4x a month so that his investment in stock-keeping is reduced? Or can we inform him that your truck is on the way?”

These internal challenges aside, analysts see external threats to the company’s central chemicals business. “This sector in India is governed by international prices. Thankfully, for now, prices have moved up while the cost of production didn’t increase in India. If operating expenses rise, the margins will be hit,” says Tholiya.

Strict environmental regulations curtailed production in China and EU two years ago, which also helped DCM Shriram and the industry, believe analysts. But Vikram says, not really. “Chinese capacity was partly restricted, but it was relocated too. So, they are still a major player in both PVC and chlor-alkali. European companies faced the same pressure, but the production was not curtailed,” he says. Tholiya sees a better future for the industry. Despite the external threats, he adds, “Since chemicals is connected with GDP around the world, the segment is expected to grow at 2-3% globally, and at around 7% in India.”

Vikram is definitely bullish about DCM Shriram’s future, and the chemical business is what he is betting big on. He adds, “Caustic and chlorine are ultimately the building blocks worldwide.” They are, indeed. These materials are used across several industries, from textile, paper and detergents to steel, PVC and pharma. He says, “To sustain growth, we are exploring downstream avenues in these products.”

The Shrirams are fully aware that there were mistakes made. But their strength lies in timely course correction, even while staying prudent in their spending. Ajay says, “We are here for 50 years, not five.”