"We’ll have an abacus in our left hand and come out punching with our right. We don’t need to compromise.” This was the belligerent Osamu Suzuki’s comment to a Japanese reporter in 1997 at the peak of Suzuki’s fierce battle with the Indian government over the appointment of RSSLN Bhaskarudu as the managing director of the erstwhile Maruti Udyog, instead of Jagdish Khattar, who was groomed to take over the mantle by the then-outgoing RC Bhargava.

An eventual compromise came about during Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s tenure, followed by the complete exit of the government in 2007. Thanks to the determined doggedness of Osamu, the chairman of Suzuki Motor, Maruti Suzuki escaped the fate of Indian PSUs by not only emerging as the country’s biggest passenger carmaker, but also the jewel in Suzuki’s crown — contributing 50% to the parent’s consolidated profit.

While Bhargava, a former IAS officer, continues to serve Maruti as its chairman — a near four-decade long association — Khattar retired from the company in 2007. Even today, the mentor and mentee believe the carmaker will continue to rule the Indian passenger car segment.

“At the peak of our socialist economy, manufacturing of cars was at the bottom of the priority list. We lived through the licensing era, survived with forex restrictions; we never gave speed money, rubbing a lot of people the wrong way; and also traversed the technology landscape,” narrates 84-year-old Bhargava, who had joined Maruti in 1981. Khattar, now an entrepreneur running a multi-brand automotive sales and service company, Carnation Auto, concurs. “When I was stepping down, many people asked, “Mr Khattar, so many players have entered the country, what will Maruti do?” I had replied, “More the players, the stronger will Maruti be.” They used to laugh when I said this, but today, concede that’s indeed the case,” says the former bureaucrat, who joined Maruti in 1993 as director of marketing.

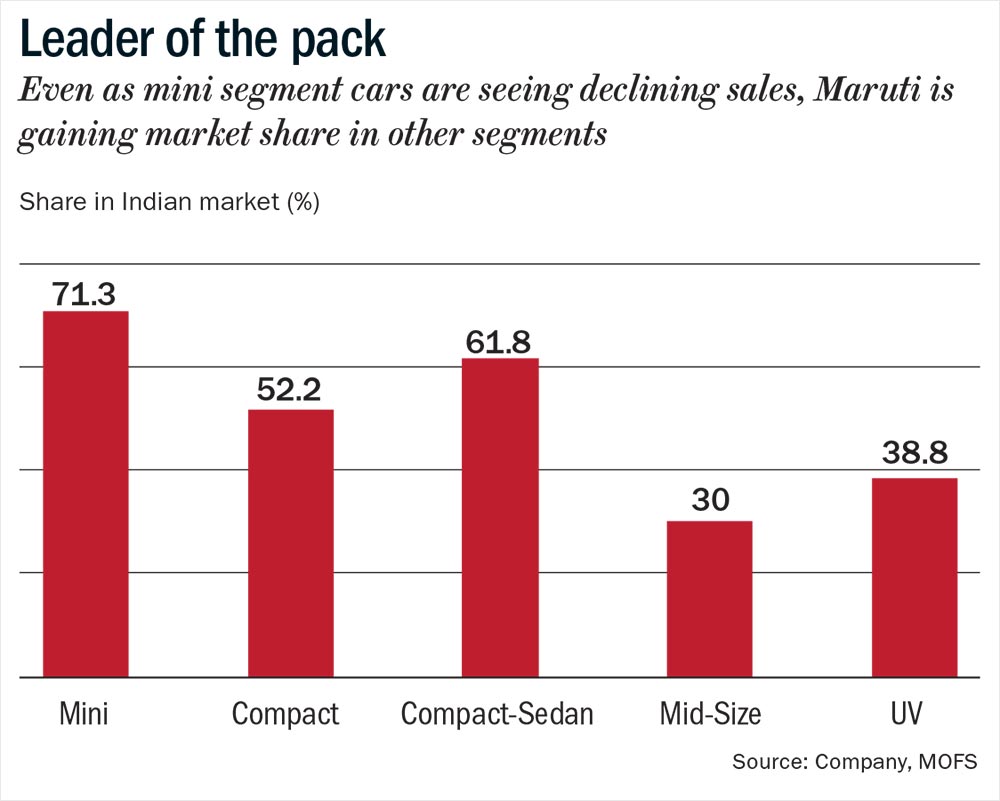

Maruti came as a disruptor in the world of Premier and Ambassador. But today, the carmaker lords over a market that has players of every hue and origin. Of the 16 carmakers in the country, 10 sell less than 100,000 units against close to two million units that Maruti sells in a year. The Japanese carmaker’s stranglehold is visible in its 61% share of the passenger car market (See: Leader of the pack). The closest, or in fact, the farthest second is the Korean chaebol Hyundai Motor at 18.8%. The difference only gets starker if one takes a look at the financial dominance of Maruti, which churned out a profit of around Rs.75 billion, with a cash pile of over Rs.300 billion and a free cash flow of Rs.59 billion. In fact, Maruti’s profitability is nearly double the combined profit of — Hyundai, Ford, Toyota, Honda, Volkswagen, Renault, Mercedes-Benz, Skoda and Tata Motors (standalone). Besides, it has been outperforming the industry in sales volume growth for the past seven years.

“Significant cost leadership, extensive distribution reach and wide product portfolio created several self-perpetuating virtuous cycles and a strong moat for Maruti, enabling it to consistently enjoy complete monopoly over industry profit pools,” states Mahantesh Sabarad, head (retail research) at SBI Cap Securities. The effusive praise is not without reason.

For an investor, Maruti has been the ultimate compounding machine — with the stock rising 26% every year since it went public in July 2003 — from its issue price of Rs.125 to Rs.6,539, against 15.03% for the Sensex during the same period. Over the past five years, the stock has compounded at 28% against 9.2% for the Sensex, on the back of 13% and 21.65% CAGR in sales and net profit respectively. The riveting growth has also come on the back of a strategy that comprised moving up the value chain, identifying product gaps and adding more muscle to its distribution reach.

Revving it up

It was in FY12 that Maruti saw its market share plunge to its lowest at 38.3%, after a violent labour stir at its Gurugram and Manesar plants, resulting in huge production cuts. The situation was further compounded by a rising yen that made imports costly. But the killer blow was the growing differential in the price of diesel and petrol, which peaked at Rs.27.19 per litre in July 2012, resulting in higher migration towards diesel cars. In fact, in FY13, for the first time ever, diesel car sales at 58% outstripped the sales of petrol cars.

A petrol car manufacturer, Maruti was caught short in the migration to diesel vehicles as its diesel engine capacity at 250,000 a year was minuscule compared with over a million petrol engines. Importantly, its staple A-segment models — 800, WagonR, Ritz and A-Star — did not have diesel variants. But seeing the customer transition, the company, in 2012, set up a plant in Gurugram that could churn out 150,000 diesel engines a year, besides procuring the same number from Fiat. In FY14, as the price gap between the two fuels narrowed, Maruti pushed its market share over 40% with sales of both petrol and diesel cars rising.

But the defining move by Maruti came when it started rolling out smart and snazzy models aimed at the new-age buyer, besides redefining the way it sold premium cars. Since 2011, Alto K10 (variant launched in 2000) and Celerio (hatchback launched in 2014) were Maruti’s only new offerings at the entry level. In 2012, the company launched Ertiga, a multi-purpose-vehicle (MPV) in the mid segment, and Ciaz, a full-sized sedan in the premium segment, in 2014. It later took a swipe at the competition by launching several new models between 2014 and 2017 at a higher price point — a premium hatchback (Baleno), a compact SUV (Vitara Brezza), Ignis (hatchback) and a mini SUV (S-Cross). But given that compact and micro-mini account for 91% of the total passenger car market, Maruti ensured that it got its model concentration right.

Renault, Ford, Hyundai and Mahindra dominated the compact utility vehicle space with Duster, EcoSport, Creta and TUV300, respectively. Developed at its Rohtak R&D centre, Brezza was the first Maruti vehicle to be designed, developed and validated in India. Today, Brezza dominates the compact UV segment with over 44% share.

Moving up the value chain did not come easy. Previous attempts to go premium with the Grand Vitara SUV in 2001 and the Kizashi in 2011 had failed dismally. Maruti engineering head CV Raman, in an earlier interaction with Outlook Business, had revealed what had led to the makeover: “Today’s customer is not looking only at the value proposition of kitna deti hai. So, in all the vehicles launched after 2014, you see a change in how we have looked at vehicles, products or the consumer.”

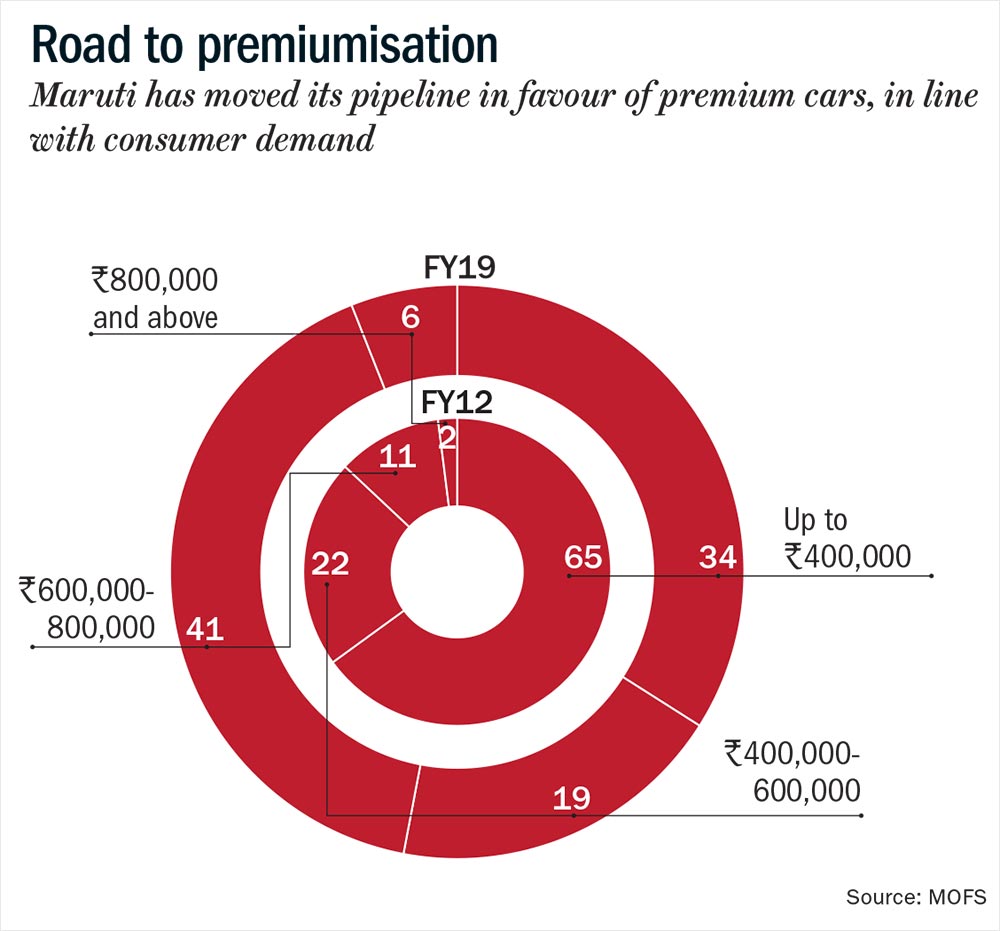

Currently, Maruti has a portfolio of 16 car models, of which nine are priced above Rs.450,000. In fact, the share of premium products in the portfolio has only increased over the years. In FY12, cars priced up to Rs.400,000 constituted 65% of sales, which has now come down to 34%. Meanwhile, the share of cars in the Rs.600,000-800,000 range constitutes 42% and cars above Rs.800,000 make up for 5% (See: Road to premiumisation). “We have traditionally followed the customer and his choices,” Bhargava puts it succinctly. In 2015, Maruti had said it would launch 15 new models by FY20, and it has stuck to the timeline. That Maruti has finally got the pulse of the buyer is evident — of the country’s top 10 best-selling cars (as of May 2019), eight models are from Maruti’s stable — Swift, Alto, Dzire, Baleno, WagonR, Eeco, Ertiga and Brezza, with Hyundai’s Creta and Elite i20 making up for the rest. Though a usual life cycle of a model is six years, with minor face-lifts in between, Bhargava mentions that there is huge stickiness for very old models. Eighteen-year-old WagonR has become the third model in the country to cross the two million cumulative sales mark, after Alto and Alto 800.

Even as the company enjoyed buyer’s fancy by moving up the value chain, it also changed the way it sold its cars. To present an experiential feel of buying a premium offering, as against Maruti’s earlier bread-and-butter models, the company set up new premium dealerships under Nexa. The non-premium brands are being sold under the regular outlets, which were rechristened as Arena. To ensure current dealers didn’t feel threatened, Maruti decided to allot Nexa dealerships only within its existing network, to the best performers.

Since its launch in 2015, the company today has 360 Nexa outlets across 200 cities that sell the premium range — Ignis, Baleno, S-Cross and Ciaz. Today, 20% of Maruti’s total revenue is routed through the premium dealership network.

While thus far Maruti’s ride has been a breeze, there are enough headwinds that threaten to make the road ahead a tough one, not just for the bellwether but the entire auto industry.

Motown bumps

Maruti Suzuki registered its highest-ever sales in FY19 at 1.86 million units, a growth of 4.7% against the industry growth of 2.7%, thus marking its seventh straight year of growth. However, the good news ends there. After four consecutive years of double-digit sales growth, FY19 has shown strains of a slowdown, that has continued well into the current fiscal with overall car sales falling 26% (till May) in FY20.

In fact, the current fiscal kicked off on a weak note for the company, with its domestic sales falling 19% in April 2019 and 23% in May. The management indicated that it could miss the two million sales mark set for the year. According to reports, the company has guided its vendors to a production plan of 1.92 million units on the conservative side and 1.99 million on the optimistic side for the year, resulting in a single-digit growth for the second year in a row.

A confluence of factors such as high fuel price and increase in insurance cost had affected consumer sentiment. But more importantly, the migration of the industry towards BS-VI regime, the government’s push for electrification of vehicles and the rise of ride-sharing apps are queering the pitch for auto industry. Hence, Sabarad says, “What we are seeing is a structural change, not a cyclical one.”

In fact, the slowdown pain has hit auto dealers the most. Over the past 18 months, a record 245 car dealers across the country have shut shop. For Maruti, with the largest dealer network of over 2,900 dealers, 13 shutting shop is not significant — Hyundai has seen 39 dealers making the exit, with Nissan topping the list at 44. Putting the closure in context, Ashish Kale, president at the Federation of Automobile Dealers Association, says, “Though dealers work on the thinnest margins compared globally, apart from car sales, we also sell finance, insurance, accessories and service to our customers, which keeps the momentum going. But, over the past several months, owing to low vehicle sales, other businesses have taken a hit as well.”

The other big challenge has been the sudden squeeze in credit to dealers from banks and NBFCs. Coupled with rising real estate and employee costs, the situation is making the business a loss-making one for dealers. “The bare minimum requirement to start an auto dealership is Rs.60-80 million (excluding real estate). Of late, the return on investment is tapering down due to stationary gross profitability and rising cost structure. Besides, with lenders asking for high collateral for inventory funding, it doesn’t make sense in a weak market,” elaborates Kale.

Interestingly, Maruti once again trumped its peers here. The company had sensed the growing challenge in the dealership business quite early on. It bought land parcels to engage with dealers on a company-owned dealer-driven model, wherein Maruti would incur the capex, and dealers would bear the operational costs. While it has been buying land for the past five years, the company earmarked around Rs.20 billion for the initiative over FY18 and FY19. That’s crucial, given that the company is looking at adding 100 new dealer partners to sustain at least 50% share of the Indian market by 2030.

While managing the network is one part of the story, ensuring sustained business in an increasingly challenging environment is a different thing. Chetan Parikh, co-promoter, Jeetay Investments and Jasmine India Fund, explains, “A huge distribution network is definitely a moat, but a carmaker needs volume to keep the network in place. If the volume starts shrinking, the moat starts eroding.”

For the auto industry, what complicates visibility into the near future is that even as manufacturers are gearing up for BS-VI transition, the government’s push for EV launch without a clear roadmap is forcing them into a future that none really know how it would play out.

Exit blues

Let’s revisit the kitna deti hai factor. In a country such as India, safety is not always the topmost priority when it comes to developing cars. In 2018, over 149,000 deaths occurred due to road accidents. The government is trying to change this. The auto industry will see the implementation of mandatory anti-locking braking system (ABS), second phase of safety regulations and BS-VI regulation aimed at curbing pollution, all in the current fiscal. Incidentally, with the price differential between diesel and petrol coming down significantly, the share of diesel models has come down from 45% in FY15 to 23% in FY19. Post BS-VI, the price differential between the two vehicle variants is expected to spike from Rs.100,000-150,000 to Rs.200,000-225,000. Besides, as the fuel price spread comes off its peak — Rs.27/litre in 2012 to Rs.6/litre currently — there is no incentive to buy a diesel vehicle.

Taking note of this trend, Maruti has decided to stop selling diesel vehicles from April 2020. Justifying the move, Bhargava says, “We won’t sell diesel cars up to 1.3 litre as we realised that the cars will be too expensive to sell. We may continue with the ones above 1.5 litre, but that’s just a probability.”

The management does not seem too perturbed about 23% of the company’s sales coming from diesel cars. “What was the contribution of diesel to Maruti before 2011? It was nil. It’s not my desire to change the revenue composition of the company. It’s an outcome and reflection of the customer’s choices,” explains Bhargava.

However, analysts believe the call is a tough one. Kotak Institutional Equities expects Hyundai Motor to gain market share, as it will be the only player selling small diesel engines. UBS Securities India’s Sonal Gupta, too, has turned skeptical. “Our ‘buy’ on Maruti was predicated on the expectation that the company would benefit from an industry shift towards petrol with the BS-VI transition. However, we did not anticipate that Maruti would discontinue diesel,” mentions Gupta in her report.

Stepping on the gas

Though the CNG network has limited coverage across the country, following the rise in petrol and diesel prices, sales of CNG cars have gone up. Since 2010, Maruti has cumulatively sold 500,000 CNG vehicles, and FY19 was the year where the company sold over 115,000 units — the highest ever in a year — ensuring its lead in the segment. Also, it is the first carmaker to offer factory-fitted CNG across a wider portfolio that comprises Alto K10, WagonR, Celerio, Eeco and Ertiga. WagonR, till date, is the most-sold CNG model. There is optimism about CNG as the government plans to set up 10,000 CNG pumps in the coming decade. But Khattar has his doubts. He says, “CNG came in 1998 but the pump stations don’t even cover 20% of the country. What is our track record? ” The other challenge for CNG is its availability going ahead. “Right now, auto fuel is getting the upper hand in terms of allocation, but I don’t see this sustaining beyond a couple of years. Today, we are power surplus, but as soon as the power deficit widens, supply will be diverted to power plants,” points out Sabarad.

Electric shock?

While Maruti expects customers to gravitate towards CNG and petrol versions, the bigger challenge is the government’s determined push towards electric vehicles. According to a 2018 World Health Organisation study, 15 of the 20 most polluted cities are in India. To bring down rising vehicular pollution and reduce dependence on crude imports, the government is pushing the auto industry towards electrification. Earlier, the government wanted the entire industry to go electric by 2030, but now it has watered down its stand, aiming for 30% of vehicles to be completely electric by then.

However, industry experts believe the government is erring in its drive. The other big hurdle is the access to the right technology for EVs. Besides, lithium ion batteries (used in EVs) are not made in India. Imports don’t come cheap. Battery makes up for 50% of the total cost of an EV, compared with internal combustion engine that makes up 15-17% of the vehicle cost. Moreover, India is not adequately equipped with infrastructure for EV-charging stations.

“You have a policy that states 30% penetration by a certain date; what happens if the customer doesn’t buy? Produce the car and keep them at a stockyard? Nobody asked the customer what his view on EV was,” argues Bhargava. Concurs Khattar, “We should allow a transition phase, with hybrid as an option.” The angst is understandable, given that the story of existing EV players Tata Motors and Mahindra Electric is not exactly an inspiring one. Till date, it’s the fleet segment that has been the testing ground for both the automakers. Even the much ambitious 10,000 EV tender from the government has not made significant progress. According to sources, of the 100-odd sourced EVs till date, several are lying unused.

Importantly, based on imported battery sets coming from China, it’s unlikely that manufacturers will be able to produce vehicles in huge volume. “If you are going to base your EV roadmap on battery availability from overseas, the numbers would be limited because most battery-makers have fully committed their capacities to global carmakers,” notes Bhargava. Though Maruti is setting up a battery plant in Gujarat and expects it to be commissioned by 2020, it’s not clear what kind of batteries would be produced.

BVR Subbu, former MD of Hyundai Motor, says, “It’s unclear whether Maruti intends to assemble batteries, go all the way and manufacture them, or set up only cell packaging facilities to meet its battery requirements in India.” And Maruti is not revealing its cards. “Globally, companies are investing in major research to lower the cost of batteries. People are looking at materials other than lithium and cobalt. Nobody knows what and when a breakthrough in this tech will come through,” says Bhargava. Amid this uncertainty, Maruti is looking to traverse down the EV path by relying on Toyota’s technology.

Tech mate

Toyota, known for its first and popular hybrid model Prius, is offering automakers and suppliers access to its nearly 24,000 patents for EV technologies. But Toyota, despite its success in hybrids, is yet to crack the EV code. In 2012, it sold about 100 eQ cars (electric version of its iQ range of mini cars), but discontinued the model over its high cost, short driving range and long charge time. In fact, it hopes to sell an EV in Europe for the first time in 2021 as it aims to catch up on the technology.

Where does Suzuki come into the picture? The two Japanese automakers entered into a tie-up almost two years ago to explore projects in environmental, safety and information technology. This gives Maruti the opportunity to move towards its hybrid dreams that it hopes to achieve in 2020. Toyota had announced that it would share the Corolla sedan with Maruti, even as it has launched Glanza, based on Maruti Suzuki’s Baleno, in India.

As per the pact, Maruti will supply its four models — Baleno, Ciaz, Ertiga and Vitara Brezza — to Toyota, while the latter will share its hybrid and EV technologies, besides its sedan Corolla. But given that Toyota is unsure if Corolla would be produced post BS-VI regime, it’s not clear which hybrid model will Maruti ultimately get.

Though Bhargava refused to share details on what was in the works, the company is reportedly testing 50-odd EVs, including an electric version of the popular WagonR. There could be a possibility that the company would also roll out a hybrid at the upper end. “This is the time to promote CNG and hybrids, and look at how battery technology is evolving,” says Bhargava.

Road ahead

While these are still early days, analysts expect the EV WagonR to be priced around Rs.800,000 and the hybrid sedan, based on Corolla platform, around Rs.2 million. Currently, the most-affordable 48-volt mild-hybrid vehicle on the road is the Mercedes-Benz C-Class that retails at close to Rs.4.4 million. That could soon be changing though. China, currently the biggest maker and market of EVs in the world, has now set foot on Indian shores. The country’s largest automaker by volume, SAIC Motor Corp, has launched its mid-sized SUV Hector at an introductory price of Rs.1.2 million. It has also launched a 48-volt hybrid option in three variants priced between Rs.1.3 million and Rs.1.6 million, making it the cheapest hybrid in India. SAIC, which is betting big on electric cars, also has plans to launch the all-electric eZS SUV in India. Given their aggression, the road ahead for Maruti could be far from easy. Could the Chinese end up gobbling the EV market like the mobile handset market? Sabarad doesn’t think so. “Cars are not use-and-throw, unlike handsets. Besides, it’s not about selling cars, but also about after-sales services and availability of spares.” Khattar concurs, pointing to the exit of Chinese two and three-wheeler automakers from the country.

Of course, there is no denying that the auto industry faces its biggest challenge in the coming decade. And the tsunami of change that could hit the industry will hit Maruti Suzuki as well. Yes, it has the backing of a strong parent and huge reserves at its disposal. But Subbu adds a note of caution: “Technology will continue to obliterate all moats and edges. The technological strength of Maruti’s parent has to be seen relative to large global players. In that league, Suzuki does not fare very well.”

With a market cap of almost Rs.2 trillion, Maruti Suzuki continues to be a market favourite. Though the slowdown in car sales tempered the stock, investors are keeping their faith. That is evident in the way the carmaker’s stock has held its ground. While the stock has come off its 52-week high and is trading near Rs.6,600, of the 54 brokerages covering the stock, 41 have a ‘buy’ rating. At 27x estimated FY21 earnings, the stock is not exactly cheap, but the market has its reasons to stay invested. “If Maruti is the only choice I have after evaluating its peers and I want diversification in my portfolio, I’d buy the stock,” says Sabarad. But does that make it a good bet for the future? “There is a risk, but have I priced in the risk adequately in the multiple? I believe I have,” sums up Sabarad.