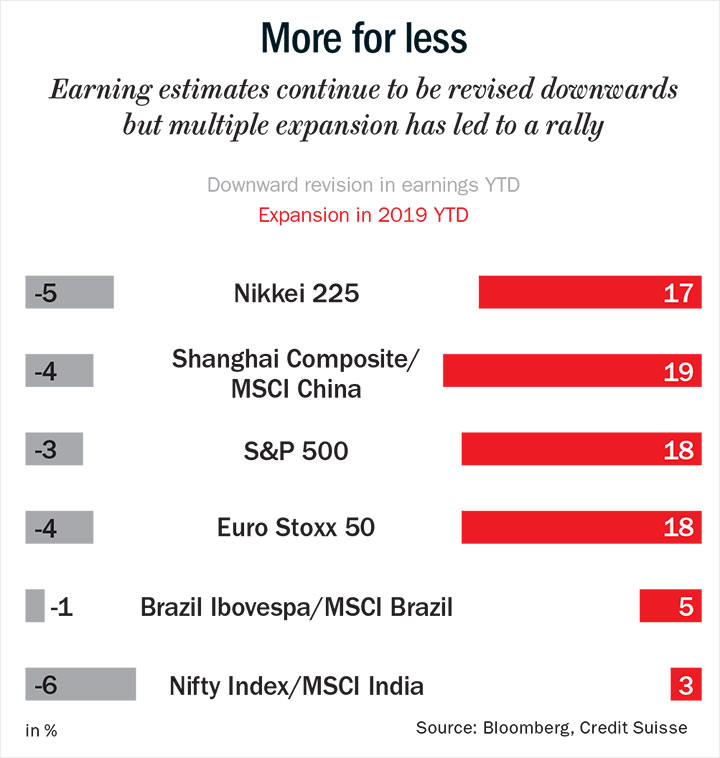

How many traders does it take to send the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) plunging 650 points? None, just a tweet from Donald Trump is good enough. Welcome to the new normal. Earlier only central bankers moved markets, now politicians do too. And presumably the worst or maybe the best is yet to come. Cohesive not to mention excessive expansionary measures by central banks have kept markets buoyant globally. Much of what is happening does not make sense any more as investors are willing to pay more and more for the same level of growth (See: More for less). Sarah Ketterer, co-founder, Causeway Capital which has $53 billion under management, is confounded by the 15% annual return that the MSCI USA Index has delivered over the past decade. “That return occurred with historically low levels of 10-year volatility. Abnormally high return should come with abnormally high risks. And the fact that the inverse has occurred, is an outcome of very strange monetary policy,” she says.

In the latter half of 2018, investors were concerned that the Federal Reserve was going to keep on raising rates and drive the US economy into a recession. With the Fed changing stance back to neutral, that worry is off the table. Investors are also not worried about lower expected earnings growth as they feel stable interest rates will eventually revive the momentum. “The biggest risk is that investors don’t believe they are taking risks. We have hit an all-time low for US market volatility on a rolling ten-year basis. Even institutional clients are not cognizant of that. Everyone has this kind of five-year window of memory,” adds Ketterer.

Another significant change that has happened is now the earnings outlook of technology companies spooks the market more than that of manufacturing companies. In the US stock market, manufacturing in aggregate is just not that big a piece and so investors hardly bat an eyelid when, in its Q12019 earnings call, 3M says the rest of 2019 is going to be challenging. Now the top-five market cap companies are all tech and that is where most of the investor attention is focused. So much so that Amazon has also entered Berkshire Hathaway’s investment portfolio along with Apple, which is now the biggest holding. Hence, even if earnings are weak on the manufacturing side, it gets counterbalanced by good earnings from Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon. Ben Inker, head of asset allocation at GMO which has $66 billion under management is not so sanguine. “We are somewhat nervous because corporate profits are extraordinarily high in the US. Historically, from these levels, they have always come down. You’ve got two possibilities: either profits somehow stay at these extraordinarily high levels and the market is merely expensive or profit margins come down and the market is kind of disastrously expensive.”

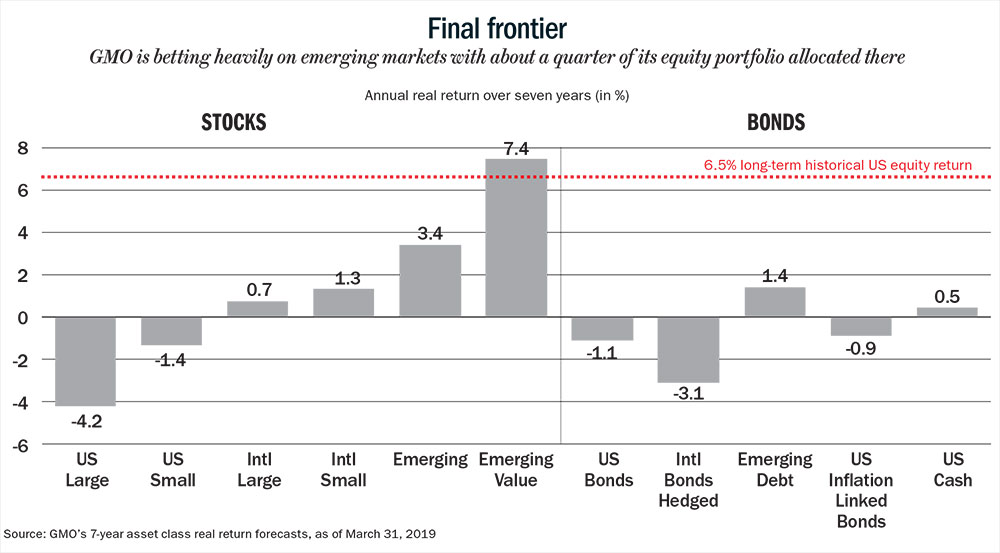

Most asset classes around the world are expensive relative to their own history. Even US cash and bond rates are very low relative to their historical rates. The US stock market has been the strongest performing since the financial crisis and shows no sign of letting up. Since the December low, the S&P is up about 22%, while the Nasdaq and the DJIA have climbed more than 27% and 19%, respectively. Inker mentions, “We really don’t own any material amount of US stocks anymore. We’ve got about a quarter of the overall portfolio in EM equities and another 15% in non-US developed market equities.”

Sky-high valuation

It is not just the folks at GMO who are complaining about the lack of bargains; the Oracle of Omaha, too, is struggling with a problem of plenty at Berkshire Hathaway. In his latest shareholder letter, he wrote,“In the years ahead, we hope to move much of our excess liquidity into businesses that Berkshire will permanently own. The immediate prospects for that, however, are not good: Prices are sky-high for businesses possessing decent long-term prospects.” So, Warren Buffett is making do by buying back his own stock. In the latest quarter, he spent $1.7 billion doing just that.

In the US, the bond market, a default safe haven, has rallied alongside the stock market. Last December, when the market dived after the talk of President Trump meddling with the Fed, the US 10-year yield fell from 3.26% to 2.34%. Now it yields 2.46% and the S&P 500 is just backing off from its all-time high after Trump’s latest tariff salvo against China. So, what gives? One explanation is that the market is now anticipating the Fed’s next move to be down. The other being that the US yield is relatively more attractive than what is available in Europe and investors are comfortable with US economic growth. That could also in part explain the strength of the dollar against the Euro. For the past six months, the Euro/dollar has been trading in the 1.12-1.15 range. It is only now that it has broken below 1.12.

Michael Kass, portfolio manager at Baron Capital, which has $30 billion under management, says not much should be read into the recent dollar rally. Traditionally, a dollar rally has been negative for emerging markets. “For most parts, the dollar has not been particularly strong against emerging market currencies. When dollar strength is not being confirmed in emerging markets, that means the risk environment is much more favourable than it was last year.”

The variant view with bond yields rallying could be that investors are now hedging their bets by not plunging headlong into equities. The broad-based S&P 500 may have just about hit an all-time high post December, but the DJIA or the Russell 2000 did not register a new high. Something similar is happening in the Indian market where the mid-cap and small-cap indices have not rallied as much as the benchmark Nifty Index over the past year. Even within the Nifty itself, there is great performance divergence and according to Credit Suisse India estimates, it currently trades at one–year forward P/E of 18.2x against the 10-year average of 15.4x.

While fixed income investors in Europe may be flocking to the US 10-year, Ketterer believes Europe is a better hunting ground for equities. “Relative to the benchmark where the US makes up over 60% of the weight, we’re underweight. But, Europe is just deeply undervalued. A lot of these European stocks are multinationals and may be a quarter of their revenue comes from the US anyway. So it’s very difficult to talk about isolating regions when there’s so much overlap,” she specifies.

GMO’s Inker though likes the emerging markets basket (See: Final frontier) as he feels it is hard to get decent real return out of the US stock market because it is expensive and on the bond side, real yields are close to zero. “It’s hard to see how anything non-heroic is going to get you the 5% to 6% real return that everybody’s kind of assuming for their long-term portfolio. We like emerging markets better than the US and developed international. If you look at the valuations on a cyclically adjusted P/E, it’s trading around 14x against 27x for the US and 21x for EAFE. So it’s significantly cheaper,” he elaborates.

India for now is an exception for being an expensive market. Inker says, “India is the most expensive market in our universe by a wide margin. Even adjusting for the higher level of quality we see at the company level, the valuations appear stretched and the growth projections appear unrealistic. For the past few years, valuations have gotten more expensive, while profitability and margins have languished.” He also feels that the Indian market has run ahead of itself. “The market has aggressively priced in the future benefits of the Modi reform agenda. While we believe most of the past reforms will be net positive in the long run, the market has overshot in our opinion. We are also concerned about Modi’s ability to conduct and complete future reforms given departures from his staff and his possible loss of majority in the government,” he adds.

Another emerging market that has frequently been hogging the headlines is Argentina. Even as Argentinean bond yields are rising, most global investors think it is a contained problem as there aren’t many other countries that require help with their external debt and hence rule out any contagion in emerging markets. Inker opines, “I think the problems in Argentina have every reason to stay in Argentina. My biggest fear for emerging markets would be if there was a bad loan crisis in China. It’s an opaque enough system and that could cause significant contagion. Even though there is fast nominal GDP growth and the Chinese central government doesn’t have that much debt itself and has the potential to bail out the system if it gets into trouble, it worries me.” Investors have long been wary of the credit growth in China where much of the lending has been government directed. The inattentive lending has led to sporadic crisis but not big enough to spark emerging market contagion. Another emerging market hotspot that investors worry about is Turkey for its linkages with Europe’s banking system. Ketterer says, “Turkey worries us because of the not so close relationship with its neighbours and its proximity to Europe and the relationship with European banks. It is a bigger economy and more impactful. So we’re watching the situation because staying within budget and correcting a massive current account deficit would be good for Turkey and yet you know they are not necessarily run by somebody who is economically minded, at present.”

Seeking inflation

Most economies, not to mention financial assets, have been beneficiaries of low rates. Now, the most obvious trigger that would cause interest rates to go up is inflation. The biggest economic mystery over the past decade or so is that the developed world has been resistant to inflation. Despite strong global growth, sporadic commodity boom and the Fed’s pre-occupation with its 2% inflation target, inflation has been largely evasive. An exasperated Buffett recently remarked, “No economics textbook I know that was written in the first couple of thousand years discussed even the possibility that you could have this sort of situation continue and have all variables stay more or less the same.”

Inker says what has been going on has been driven by a couple of important temporary factors. The first being the rise of China as a manufacturing centre. After joining the WTO, its share of global exports has exploded as it was a cheaper place to build stuff. That has been strongly disinflationary. The second factor is the relationship between unemployment and wage growth has been much weaker than it used to be.

One reason could be the globalisation of labour markets where technology has made it easy to offshore jobs. Inker thinks China’s golden run as a cheap manufacturing destination is about to end as unit labour costs are rising pretty fast. He also adds that, for stuff that isn’t built in China yet there may be a good reason why it’s not built there. So their ability to absorb evermore share of manufactured goods may be ending. He though is not as sure if the globalisation of labour markets is over.

Jobs moving overseas be it in manufacturing or services has been a bone of contention for President Trump. Right now, the US labour market is pretty buoyant and hence service jobs moving overseas might not have been paid heed to. Not only is US unemployment very low, there has been very minor acceleration in wage growth. If one indeed assumes a global workforce then wage inflation could take a long time to show up. Unless of course, induced by intent, a very real possibility which we will come to a little later. “Markets are priced as if the potential of inflation is non-existent. And I think that’s dangerous. We could get material wage growth and the Fed would quickly realise the neutral rate is higher and it would have to go above neutral to try and control it,” cautions Inker.

Incumbent resistance

Going by the latest knee-jerk reaction to Trump’s tweet, “The United States has been losing, for many years, 600 to 800 Billion Dollars a year on Trade. With China we lose 500 Billion Dollars. Sorry, we’re not going to be doing that anymore!”, were investors taking it a little too easy? The prospect of a trade war between the US and China did rattle markets in 2018 since trade wars reduce economic activity and increase inflation. That worry had largely dissipated as investors believed there will be a deal as it is in nobody’s interest to protract the conflict. Kass says it will be tough for Trump to continue with his aggressive protectionist stance.“You can either have major margin disruption and an earnings recession in the US or you have inflation and then both would affect the US capital markets. The collateral damage is too big to actually follow through with the highest level of threatened action.”

The US has largely been threatening tariffs on manufactured goods, which is unquestionably inflationary. Such a move does impact the manufacturing sector, but not necessarily labour markets. There is no tariff on your call center in the Philippines or your IT support in India or any other large work that’s getting shuttled around the world. Well, that is theory, for all rationality goes out of the window if politicians want to get re-elected. Good politics does not necessarily translate into good economics. Trump’s re-election in November 2020 hinges on the market staying buoyant. So far, everything has gone right for him economically and he would want the feel good to continue. Hence, he would do everything in his power to not let the Fed raise rates as that is the only bogeyman that could derail the DJIA’s gravy train.

There will certainly be posturing of some kind in the run up to the US elections given the head-on stance that Trump likes to adopt. But Inker doesn’t seem to be fretting over it much. “One of the things that the market has taken from the various tweets and other statements from Trump is: You don’t necessarily want to pay too much attention to what he says until he actually does something. I don’t know whether harsh words on the campaign trail would translate into action because much of the posturing hasn’t really been followed up with policy,” he says.

Populist clamour

Besides the clear and present hollering of politicians, there are other risks which investors would be better off paying heed to. Having sent price discovery for a toss, monetary policy is in uncharted territory. Kass says while the central banks in Europe and Japan may not have ceased quantitative easing (QE), that monetary gasoline itself is about to hit a dead end.“The ECB balance sheet already owns just about all they can own. Of their specific kind of mandates as to credit quality, how far out on the risk spectrum, percentage of total bonds in existence of any country…they are reaching those limits,” he points out. As for Japan, the central bank has truly adopted QE infinity. The situation is getting a little bizarre as the central bank’s bond and equity holdings now exceed nominal GDP. “You are looking at negative interest rates in Japan and a very large portion of outstanding debt in Europe and Japan is another signal that they are reaching the physical limits of QE and monetary policy”, adds Kass.

The Fed is not quite in that position but not that far either after shrinking its balance sheet by about half a trillion. In fact, if President Trump had his way, he would have the Fed lower rates as of yesterday. His assertion that the Fed cut rates by 100 basis points flies in the face of a strong jobs market. His insistence, of course, conveniently ignores that during his presidential campaign, he lambasted the Fed for keeping rates artificially low and questioned its independence. In September 2016, he had said, “Janet Yellen should be ‘ashamed’ of what she’s doing to the country. By keeping interest rates low, the Fed has created a ‘false stock market’…I used to hope that the Fed was independent. And the Fed is obviously not independent. It’s obviously not even close to being independent.” Indian investors might have just experienced a sense of déjà vu.

Ironically, if one goes by how the US 10-year has behaved since December, investors are discounting a rate cut by the Fed. Question is will it come through. Of course, that is what Trump wants. That self-serving bias is fine so long as it does not become endemic. Ketterer says, “What makes this election all the more fascinating is that it is hard to know which populist would be the loudest. Anything unexpected, politically, is a risk for the market but Europe looks more fragile to us in terms of populism than the US.”

His rabid outpouring aside, the Democrats have really no economic plank to dislodge Trump, so they are highlighting social inequity and how those with assets have unequally benefitted from the economic expansion over the past decade. Among the left leaning candidates of the Democratic Party, there is a lot of talk around Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), where fiscal spending gets priority over monetary policy. Kass says EMs are moving in the right direction with respect to political emphasis and policies while the opposite is true for large buckets of the developed world, particularly UK, pockets of Europe and the US. “There the entire political discourse is about how to be balanced, how to redistribute wealth and resources away from capital owners and corporations and return some portion of that to labour and the lower class. That represents a threat to corporate profit margins down the road and to asset values,” he says. While increased fiscal spending in the US does raise the specter of a weak dollar, emerging markets might just end up as unintended beneficiaries.

Visible hand

Unless it gets out of hand, the resulting higher inflation from fiscal spending could make monetary policy effective again. It is hard to lower rates when nominal rates are close to zero, and by raising inflation, the Fed could gain greater control over real interest rates. Ketterer ponders, “I don’t think societies can persist very long without some sort of backlash, and you see this in Europe with this strength in recent years, of populist politicians promising wage earners with benefits, because they feel extremely disenfranchised. So, what may undermine this ebullience in the market, might not necessarily come from an economic change, as much as a sociopolitical one.”

It is the nature of markets to be manic depressive but now even political leaders are turning out to be unpredictable. Inker points to Brazil which was priced for disaster a couple of years ago. “They haven’t exactly fixed many of their structural problems but right now investors are giving them the benefit of the doubt. One of the things about charismatic leaders is they tend to be better at promising than delivering but they often say things that investors like to hear.” This time around though, they might just end up saying things that investors do not want to hear.