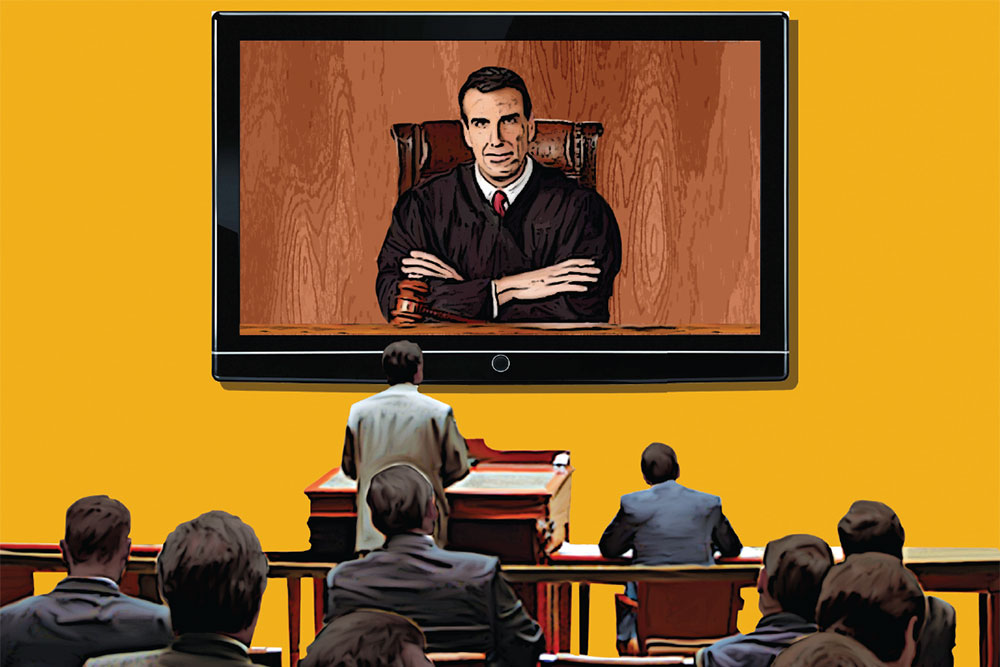

There has been a lot of heat generated in the past few months with the Supreme Court of India trying to regulate press reporting of court proceedings. Despite a court ruling, however, there hasn’t been much light shed on the issue of the right of citizens to have accurate information of court proceedings. The Court tried to balance the right of the press to its freedom of speech with the right of the public to have access to accurate information about court rulings. We have an opportunity to make the issue of mandating accurate reporting by the press an academic one by permitting court proceedings to be webcast. Information received directly is not prone to distortion as is that strained through the media.

The philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham said, “Publicity is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion, and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps the judge himself while trying, under trial.” While the principle has been used to have open-court hearings, modern technology permits the openness to happen at a superior level. The recording and webcasting of court proceedings is neither an extreme idea nor is it unheard of internationally. Thousands of courts worldwide have implemented it. Various American states, European and Commonwealth countries, besides international tribunals, have mandated the use of video recording in their courts.

Various Indian high courts, on prodding by litigants, have looked at the option but stopped short of looking at it systematically. The following quote by a high court judge reflects a similar view in parts of the higher judiciary. “I consider that it is high time that the court and state should consider introduction of authenticated audio/video recording of the proceedings in all courts, more specifically in district courts. In my view audio and video recording shall help smooth functioning of the district courts where the district judges and civil judges work in adverse circumstances and do not have power of contempt... This will also discipline not only the judges who do not come to the courts in time but will also discipline the advocates and litigants who many a times try to obtain order from the court either by show of force or abusing, more specifically when an advocate is an accused before the court and entire bar surrounds the judge. I, therefore consider that it is high time that high court should consider the introduction of such measures of audio/video recording in trial courts as well in this court.”

Various chief justices of India have discussed it in public speeches. Remarkably, I was unable to find an argument by a judge arguing against the concept of video recording with the exception of comments on trial by media. With that caveat, the benefits of webcasting are too many to ignore any longer and the cost of implementation, once large, is now minuscule. Webcasting humanises judicial bodies, allows the viewer to witness and associate the individuals in the webcast with the content and the outcome, and improves trust and institutional credibility. The introduction of webcasting would bring transparency; increase affordable public access to the judicial system; afford citizens a form of legal education; act as a powerful check on misconduct by litigants, advocates and judges; promote confidence in the administration of justice; foster respect for the legal system; enhance the performance of all involved by ensuring close scrutiny; and enable preservation of records for later generations to analyse. Webcasting is also an important acknowledgement that what transpires in courtrooms is public property and would connect the judiciary with the people in new ways.

A US court has held that “actually seeing and hearing court proceedings, combined with commentary of informed members of the press and academia, provides a powerful device for monitoring the courts”. One would not be able to guess that the author of the following quote is not a liberal US judge but a Chinese one from Beijing: “The establishment of the live broadcast website not only plays an active role in strengthening open trials, promoting justice, improving efficiency and enhancing judges’ trial level, but also makes it more convenient for the public to supervise the people’s courts”. Similarly, the UK Supreme Court has a YouTube channel, which shows judgements being read in open court.

Finally, what better learning is available for law students and others who are interested not just in the legal and judicial system but the complex workings of the entire democratic system and all its citizens and institutions? The entire system of conflicting rights, responsibilities, duties and privileges can be learnt by observing the final word on all these issues. This would also enable people to be more responsible and more aware of their rights. I can only imagine the power of the hearing and the decision in the famous Kesavananda Bharti case (a sharply divided ruling of the entire strength of the Supreme Court of India in 1973) and its impact on shaping modern India as it is today. The case arguably separates our country’s present from that of Zimbabwe or North Korea.

There are, of course, some valid arguments against webcasting every court proceeding and these must be considered seriously. A public telecast may affect right to fair trial as the people or the media may prejudge the issue, and the presumption that every person is innocent would get compromised. There could be an impact on the privacy of witnesses and parties, particularly in certain kinds of cases such as divorce. Thus, a category of sensitive cases such as criminal trials, personal cases or those cases where the safety or privacy of any of the parties or witnesses is compromised must be excluded from this new openness. Few would claim that a copyright case requires a protection from similar exclusions.

In 2005, the Supreme Court ordered that proceedings in the Jharkhand legislative body be video recorded. It is now the turn of Parliament to return the favour and pass a law mandating the recording of all judicial proceedings with narrow exceptions. The result would be as dramatic and positive as the governance earthquake that we call the Right to Information law.