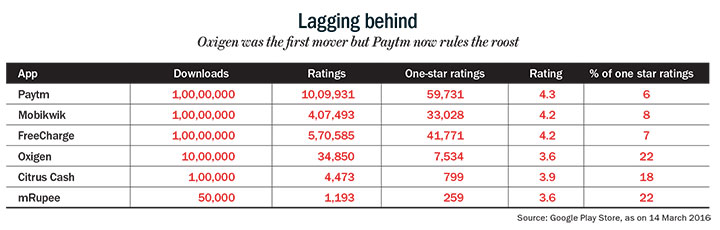

In September 2015, Nandan Nilekani made a provocative speech at the TiE Leapfrog event in Bengaluru. Referring to payments banks, the Infosys co-founder said the Indian financial services industry is on the cusp of a ‘WhatsApp’ moment. A WhatsApp moment, as Nilekani puts it, is when new-age start-ups shake up a clueless old order to emerge dominant, just like WhatsApp did with the telecom industry, disrupting the SMS business to become the world’s biggest messaging service. A case in point, he said, is mobile wallet Paytm, which got a payments bank licence in August 2015. After having raised $1.3 billion, Paytm, today, facilitates more purchase transactions in volume terms than any Indian bank.

Nilekani is not alone in pitching payments banks as the next big thing. The prevailing view is that banks’ market share is up for grabs given their legacy ‘mindset’. Sharad Sharma, co-founder, Indian Software Product Industry Round Table (iSPIRT) says that the banking industry is in the throes of a non-linear change. “It happens rarely. And when it happens, big companies don’t know how to deal with it. In fact, they have never had to deal with it. Banking is a bundle of three things: identity, payments and credit. Non-linear change happens when bundles get unbundled,” he says.

Consider debit card payments, which work on two-factor authentication (the card and pin). Nilekani, the former UIDAI chairman, pitching Aadhaar, spoke of how the database, using biometrics, could replace the pin while the phone acts as the card. “The incremental cost of adding an iris camera to a smartphone is $5. In the next 12-18 months, phones with iris capability will be launched. And you will soon have a device lying in your pocket that allows a single-click two-factor authentication in real-time,” he pointed out at the TiE event. Now, he added, apply this to the whole industry, in a country of over a billion people with Aadhaar cards, bank accounts and mobile phones, and a brave new financial world will emerge.

There is no doubt that technology will change the banking industry. And to be fair to Nilekani, it will morph into a different shape, but in all probability banks would be leading this change. Contrary to popular perception, they are already navigating the digital curve and aren’t far behind nimble-footed start-ups in offering mobile apps or digital services. In fact, they are tapping social media too.

On-the-move banking

Smartphones, bankers say, are part of the natural evolution in banking after ATMs and internet banking. In fact, many private and PSU banks have launched their own mobile apps to cater to users across the ecosystem. Some have also launched mobile wallets, wherein customers from any bank can deposit money for transactions. Then again, some have released two apps for mobile banking – one that works via internet and second for users without internet access, which works through SMS, missed calls or in-app messaging.

The country’s oldest and largest bank, SBI, too seems to be in sync with the changes afoot unlike the incumbents in Nilekani’s story. “In the next five years, mobile will be the new bank and digital payments/acceptance systems will move to micro-enterprises like kirana shops, coffee shops etc, which mostly work on cash now,” says Manju Agarwal, deputy managing director, corporate strategy and new business, SBI.

A Bank of America-Merrill Lynch report estimates that mobile transactions will grow to 10% by FY22 from 0.1% in FY15. To ensure this, besides launching apps, banks have also tied up with vendors and leading e-commerce players. For instance, Kotak Mahindra Bank has partnered Goibibo, keeping its urban customer base in mind. “Our customers can book domestic, international flights, hotels or buses directly through our mobile banking app. They don’t need to enter credit card or debit card details. Data flows seamlessly from the banking app to merchant app, thus reducing transaction failure rates,” says Deepak Sharma, head of digital initiatives at Kotak Mahindra Bank, adding that transaction failure rates are 30-35% otherwise. After the tie-up, the Kotak app, he says, sees around 7,000-8,000 monthly transactions for travel bookings, and is growing at 30%. Besides, with the service charge (around Rs.250-300) waived off and additional special offers, Sharma says users can end up saving Rs.800-900 on every booking compared to traditional e-commerce sites.

Kotak was also the first to foray into social banking with the launch of Jifi in early 2015. Its other services include hashtag banking through Twitter and KayPay, a bank-agnostic instant transfer platform that allows users to transfer money to their Facebook contacts. Similar apps that allow money transfer without cumbersome account details have been launched by other private sector banks. These include PingPay by Axis Bank, Chillr by HDFC Bank and Pockets by ICICI Bank. However, they differ in terms of who can transfer money and through what platforms. PingPay and Chillr need the sender to be an Axis or HDFC customer, while the recipient can be an account holder at any bank. As for ICICI Bank, executive director, Rajiv Sabharwal, says, “70% of Pockets customers are non-ICICI account holders.”

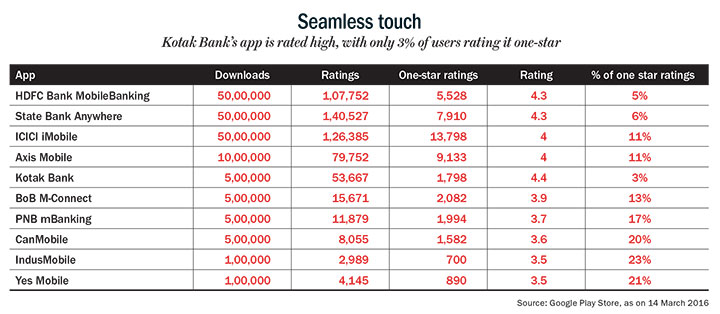

Apps around social media though haven’t gained as much traction as banks would have hoped. “Close to 6-7% active online customers have attached their social credentials to their bank accounts. That number is growing but we would love to see them grow much faster,” admits Sharma of Kotak. Users have many channels to transact and will need a compelling reason to continue using social banking. With apps, the trick, Axis Bank’s retail banking head, Rajiv Anand says, is to find the right balance between convenience and security. Currently, the highest rated banking apps, at par with fintech start-ups like Paytm and Mobikwik, are the ones launched by Kotak Mahindra Bank, HDFC Bank and SBI (see: Seamless touch).

Digital DNA

Besides investing in mobile wallets and apps, banks are digitising internal processes to reduce costs. “We’re transforming ourselves into a full-scale digital bank,” says Nitin Chugh, head of digital banking at HDFC Bank. His bank is fine-tuning all product lines and touch points to transform the way it interacts with the customers. Kotak’s Sharma adds that there are many benefits of digitisation — smoother customer acquisition, higher transaction rates, reduced cost of transaction and better customer feedback. For instance, he says, online customer acquisition is 40% cheaper.

Branches are also undergoing a change. HDFC, for instance, has two-man branches, with technology doing the rest of the work. Agarwal says SBI has recently automated instant loans against fixed deposits and shares, adding they have also put in place cash deposit machines, cash handlers and passbook printing machines for customers. Axis’ Anand quips that many customers in rural and semi-urban areas are already using mobile phones to save time and money spent on travelling to faraway branches.

But branches are unlikely to become obsolete. “Branches will get repurposed, and shrink in size but they will continue bringing in new customers. While address change or cash withdrawal may not happen through branches in the future, mortgages, investment and advisory services will take place there,” says Sharma of Kotak. He also points out the need of branches for current account holders, who deposit and withdraw cash on a regular basis.

Turf protection

Not only are banks getting tech-savvy, United Payments Interface (UPI) [for which Nilekani is an advisor] is another initiative by banks to fend off new entrants. A mobile platform developed by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), UPI currently has 30 banks on board. The Immediate Payment System-based app allows users to send and receive money across banks using their Aadhaar number, mobile number or virtual address, without entering account details. “If you go to a shop or use a taxi service, the shopkeeper or the taxi driver can collect money through UPI. All you have to do is give your virtual address instead of bank account number,” AP Hota, managing director and CEO of NPCI, had said in an earlier interview. UPI will allow inter-operability, feels Sharma of Kotak. “It is a great initiative, like roaming was for telecom operators. It helps everyone by creating a large acceptance network. Today, there are fifty wallets, but they are not acceptable everywhere.”

In this war for transactions, both banks and payments banks are after a strategic asset: transaction data. “The more customers transact through your channel, the higher balance you maintain and there’s positive impact on the liability side. On the lending side, there’s deeper appreciation of credit worthiness, based on data such as whether the customer pays utility bills and electricity bills on time,” says Yashraj Erande, partner, Boston Consulting Group.

Smug as ever

Private sector banks are winning the digitisation war as of now, with the exception of SBI, whose mobile app – State Bank Anywhere – has 5 million downloads. Its Play Store average rating of 4.3 is at par with HDFC Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank, which are the leaders among private sector banks. “Customers need convenience, good user experience, transparency, faster turnaround time, competitive rate, that is what we’ve done at the bank level,” says Chugh of HDFC Bank.

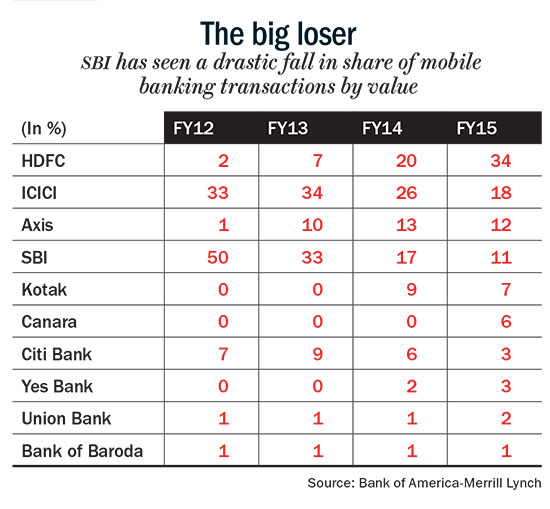

Despite holding 70% of the country’s banking assets, state-run banks account for a miniscule share of total mobile transactions, according to RBI data. For the month of December 2015, they contributed just 19% of total transactions in value terms and 48% in volume terms, with SBI alone bringing in 37% of total transaction volumes and 13% of total transaction value. “At a sector level, the top banks are making all the right moves, however, the long tail of PSU banks’ tech architecture and payment infrastructure is really bad. Suffice to say the top banks are doing a great job, staying neck-to-neck with the payments banks, but this long tail of PSU banks will feel some heat,” says Erande of BCG. He cites the bureaucratic ways of PSBs as one of the reasons. “Today, the procurement process for tech in a PSB takes a long time – by that time, your competitors will have already launched five versions.”

BofA-ML backs HDFC Bank as the best-placed horse to win this race. “While all peer banks have mobile banking, HDFC’s 30% share of the credit card market, 18% share of the RTGS market (81% of payments) and 34% share of the mobile banking means it is likely to be the biggest beneficiary as digital banking gets underway.”

The report says that HDFC’s credit card market share will help it “capitalise on key transactions effected through online payment gateways and e-commerce players.” Moreover, it adds, HDFC can leverage its many merchant tie-ups as more transactions are routed digitally and offer extra discounts for online shopping.

Owing to its strong merchant network, the average ticket-size of mobile transactions routed through HDFC is Rs.23,103, more than double the average ticket size of Rs.9,410 across all banks. Further, SBI’s average ticket size is Rs.3,369, reflecting low-value retail transactions. Meanwhile, the average value of transactions on mobile wallets (PayTM, MobiKwik, Oxigen, etc.) is Rs.250-300.

No big bang

While banks agree that payments banks have made the industry more technologically agile, Nilekani’s WhatsApp-style disruption is unlikely given the structure of the mobile payment ecosystem. India follows a bank-centric model, so all transactions – mobile, credit card etc – are routed through the banks’ payment gateways.

“Banks remain the pivot through which all payments will be effected in India. To that extent, the customer will almost “always be of the bank”, in part owing to the regulations. In India, mobile banking will continue to adopt the ‘bank centric’ model. The disintermediation being done by telcos, payments banks (proposed) or the network-based players such as Paytm or Mobikwik is unlikely to create major disruption,” says the Bank of America-Merrill Lynch report. Some bankers even say that payment banks will only enhance their business by improving financial literacy. “Financial literacy in India is extremely low, there’s enough room for new players to come in and improve it,” says Sharma of Kotak.

In fact, banks have been aggressively tying-up with the payment licence winners. IDFC, ICICI, SBI, Kotak have already tied up with various corporate entities who have managed to get a payments bank license. For banks, it is a way of staving off competition from telecom companies besides trying to acquire new customers to whom they can cross-sell. But from a payment banks’ perspective as well, the tie-ups give them access to banks’ financial expertise and branch network.

In the end, for legacy players as well as payment banks, it is about acquiring more customers. Abhishek Kumar, an engineering graduate, counts himself as one of the early adopters of mobile payment technology. “Apart from great discounts, I use Paytm because of low transaction failure rates,” he says. But Paytm’s advantage of convenient, reliable transactions, by circumventing the tedious two-factor authentication, may be lost once UPI is functional. While Kumar tops up his e-wallet for Rs.1,000-2,000 regularly for daily needs like food and groceries, the bulk of his savings stay in the bank. He says he’s unlikely to increase the amount even after Paytm starts offering interest as a payment bank. However, Kumar adds, “I want to make large-ticket transactions without having to use netbanking, but they need to have more merchant collaborations.” In other words, the two factors attracting users like him to providers like Paytm will have to be maintained: reliable transactions and continued discounts.

The upheaval that WhatsApp caused in the telecom industry is a far cry from what’s afoot in banking. When Jan Koum’s WhatsApp crept in, telecom companies were busy fighting each other for market share in a maturing marketplace. On the contrary, the banking sector in India has always been protected under the garb of regulation and operated as a quasi-cartel. Given that even payment banks, brought in to increase financial inclusion in the country, are hooking up with them, there is not much for the incumbents to worry about.