In May 2020, Cyclone Amphan ripped through eastern India, leaving behind a trail of devastation that wiped out assets worth over $13bn. One of the costliest storms to ever hit the region, Amphan was a reminder that climate change is no longer dystopian fiction—it is already unfolding across India.

Record-breaking heatwaves, erratic monsoons and intense cyclones are no longer one-off events, but are becoming more frequent, severe and taking a heavy toll on lives and livelihoods. The economic cost, meanwhile, is spiralling.

In 2021, India incurred climate-related losses amounting to $159bn, roughly 5.4% of its GDP, according to Climate Transparency, an advocacy group. By 2022, the hit had jumped to 8%, based on a study by the University of Delaware's Gerard J. Mangone Climate Change Science and Policy Hub. Asian Development Bank projections indicate that GDP losses could reach 25% by 2070. A 2021 study published in Nature by three scientists from the German state-funded Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts Research pegs income loss at 22% for South Asian countries, including India, by mid-century and warns that without sharp and immediate emission cuts, the economic fallout in the second half of the century will be severe.

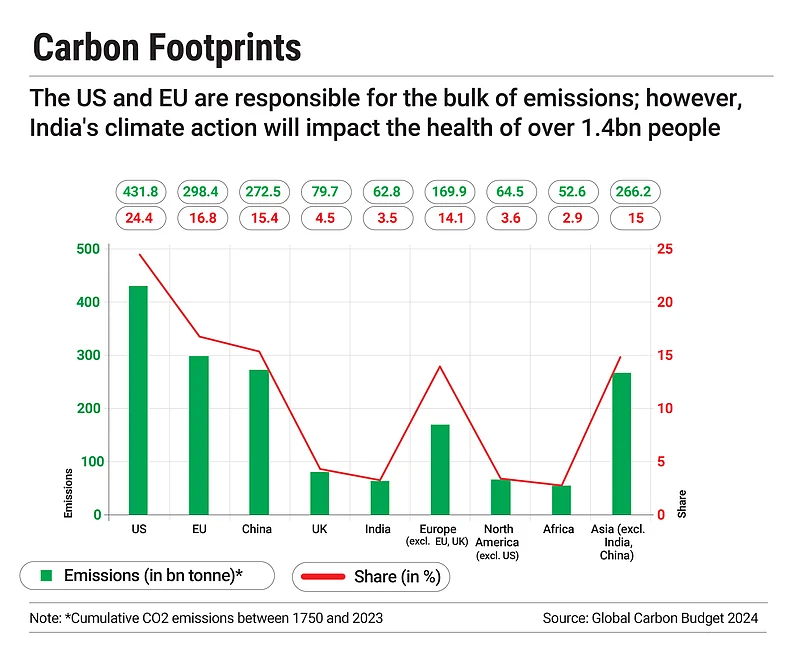

Yet, India plans to hit net zero only by 2070—two decades behind the global target. At that pace, the country will almost certainly overshoot the 1.5°C warming limit. Adherence to that threshold, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says, is non-negotiable—an existential imperative, especially for vulnerable nations like India.

India’s 2070 Struggle

When India unveiled its Net Zero 2070 plans at the Glasgow COP26 in 2021, it was hailed as ambitious, even historic. But how ambitious was it, really? On closer examination, the 2070 target appears to be less of a climate goal and more of political convenience.

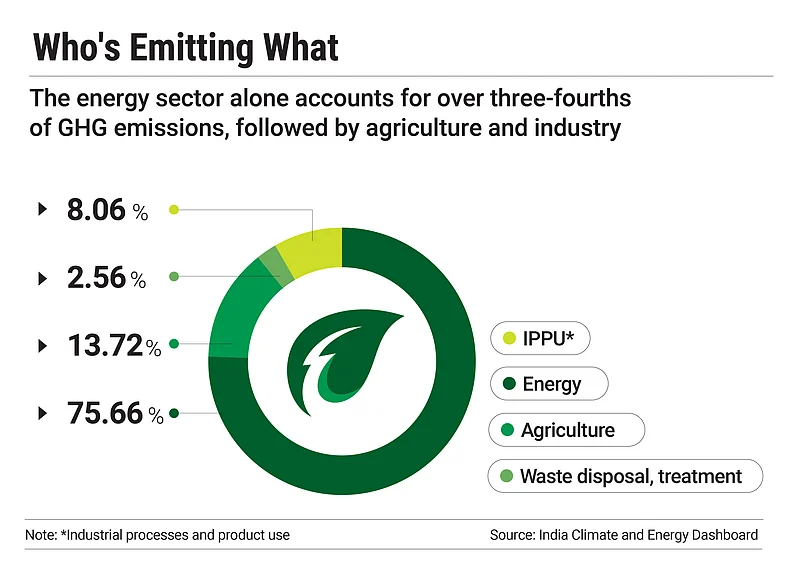

At Glasgow, climate analysts and negotiators argued that India’s 2070 pledge was pragmatic, given its social burdens and deep-rooted inequities. Over 300mn Indians still live on less than $4.2 a day. But India is also a rapidly growing economy with massive energy needs—making a just and urgent transition to clean energy both essential and unavoidable. As the country’s economy expands to an estimated $8.6trn by 2040, its energy appetite will nearly double, according to the International Energy Agency’s India Energy Outlook 2021. Today, over 70% of that demand is met by fossil fuels, and the energy sector alone accounts for more than three-fourths of the country’s emissions, followed by agriculture and industry.

Sure, India’s socio-economic realities make the 2070 goal appear grounded in justified caution. Yet that caution must not become inertia. The challenges are real—but the consequences of delay are far graver. Vulnerable populations will suffer more from unchecked climate events than from a managed transition. Every rupee spent on early action will prevent multiple rupees in loss, displacement and disaster recovery down the line.

For a sense of how daunting even the 2070 goal is, consider this: India needs an estimated $10.1 trn to achieve the transition—about $200 bn a year over the next 45 years. Against this, tracked green finance reached an all-time high in 2021–22, but fell far short at around $50 bn, barely a quarter of what’s required. Meanwhile, India secured just $13 bn for renewable energy in the last financial year, compared with an estimated $68 bn needed annually to meet its 2030 non-fossil power goal—underscoring the massive investment gap, according to the energy think tank Ember.

Worse, the global funding pipeline is far from reassuring. Against the trillion-dollar demand of developing nations. While India has expanded its renewable capacity, the momentum is undermined by chronic hurdles—supply chain snags, patchy grid connectivity and high energy storage costs.

Moreover, coal remains central to India’s energy plans. Although the pace of additions has slowed, coal capacity continues to rise. According to the Central Electricity Authority, India’s installed coal power capacity reached 213 GW in March 2024, up from 205 GW in 2021—highlighting how coal continues to expand even amid net-zero commitments. “We give coal-fired power plants generous long-term contracts that insulate them from competition created by cheaper solar. We have an institutional structure that is at the moment focused on supporting incumbent polluting technology,” says Sugandha Srivastav, environmental economist, Smith School of Enterprise and Environment, University of Oxford.

Even coal phase-out raises difficult questions of just transition. About 3.6mn people depend directly or indirectly on coal for their livelihood. If the illegal and informal coal economy, including people involved in allied services, is considered, the number touches 15–20mn. Pulling the plug too quickly could devastate communities already on the margins. But delaying too long could prove just as ruinous—climate disruptions threaten to erase the very livelihoods the coal economy sustains. The transition must be just, but it must also be urgent.

While the social costs of transition are real, the costs of inaction are far greater. Experiments in green hydrogen and green steel offer hope, but are unlikely to scale within the next 15–20 years unless costs drop dramatically. According to the IEA, green hydrogen production costs in India range between $4 and $5 per kg—more than double the cost of grey hydrogen derived from fossil fuels. Meanwhile, BloombergNEF estimates that green steel production globally remains 60–70% more expensive than conventional methods. Without policy-driven incentives and industrial-scale pilots, these technologies will remain locked in the lab.

“Delay is no longer an option for a tropical country like India, facing faster, harsher climate impacts from the warming Indian Ocean and melting Himalayas—unlike slower-changing high-latitude regions, we can’t afford to wait,” says Roxy Mathew Koll, climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology. Early investment can reduce long-term adaptation costs. According to Bloomberg, every year of delay beyond 2050 could cost the world an additional $1.3trn.

Cost of Catching Up

If the 2070 target is already so uphill, what would a 2050 deadline demand? The short answer: radical ambition and sweeping change.

India must speed up its transition—even if the path appears unnervingly steep. Experts say a 2050 net-zero target may be a stretch, but isn’t out of reach. The real question is not feasibility but whether the country is ready to make tough choices. “It’s always about trade-offs. The question is what we are willing to sacrifice as a country and society,” says Vaibhav Chaturvedi, senior fellow at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), a think tank.

That sacrifice will not come cheap. Achieving net zero by mid-century would require sweeping overhauls across power, mobility and industry—each with significant upfront costs. Electricity tariffs could rise. Government spending may have to be redirected from essential services. However, a delay will only increase the eventual cost of transition.

Under an accelerated pathway, India’s financing requirement would shoot up to $13trn, according to BloombergNEF. Strategic research provider says there’s only one way forward: a radical decarbonisation of the energy sector. All unabated fossil fuel power must exit the grid by 2045. Emissions from power, transport and buildings must peak this decade. Industry must follow by the early 2030s.

That means by 2050, India’s power sector must run entirely on clean energy. Wind and solar installations must scale up to 4,328 GW, from under 200 GW in 2024. Energy storage—from just 5 GW today—must rise to over 770 GW, mainly via pumped hydro and batteries, per BloombergNEF estimates.

“India has a unique opportunity to build future systems from the ground up,” says Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at the Columbia Business School. “But it needs massive investment in emerging technologies and policy frameworks that enable local manufacturing of renewables and storage,” he adds.

Hydrogen use must rise tenfold to 64mn tonnes by 2050, and carbon capture must scale up to 1.4bn tonnes annually, per BloombergNEF. All this must happen if India is to have even a fighting chance of achieving the 2050 net-zero goal. “India needs to revisit its policies supporting the old paradigm or implicitly subsidising it and revise those policies,” says Srivastav.

Even if the 2050 timeline appears unrealistic today, the cost of not pursuing it is far higher. Delay will not make the task easier—only more expensive, more disruptive and ultimately unavoidable.

Solutions That Can’t Wait

India’s early transition could reset the climate clock across the Global South. However, for that to happen, it must make all the right moves across sectors, instead of waiting for largesse from the developed world.

Referring, for example, to the hard-to-abate steel sector, Astrid Grigsby-Schulte, project manager, global iron and steel tracker, Global Energy Monito, says, “India’s current targets reinforce a carbon-heavy trajectory. The steel sector must pivot—retire blast furnaces, scale up electric arc furnaces, shift to hydrogen-ready DRI [direct reduced iron] and explore breakthroughs like electrolysis and biomass-based reduction.”

“For this, India could follow China’s model of adding only as much new steel capacity as it retires,” she says. Strong public-private partnerships and government-backed pilot projects are key to driving innovation. “Liberalising and privatising India’s power sector will also help, creating a system where the cheapest technology wins,” notes Srivastav of Oxford’s Smith School.

Deepening its carbon markets and strengthening policy signals are urgent next steps. Sectoral-emission caps must be enforced to compel industry to act. “If India hopes to be Viksit Bharat by 2047, why not a sustainable Bharat, too?” asks Mahesh Ramanujam, president and chief executive of Global Network for Zero, a net-zero advocacy group.

Policy clarity is just as critical as capital. The funds exist. What’s missing is a coherent signal on long-term investment priorities. “Why build inefficient buildings now, only to retrofit them later at a higher cost?” asks Ramanujam. “Make green construction the default. If someone opts out, raise their lending rates—even by 10 basis points—to steer better choices.”

India must also invest in its people. The workforce must be future-ready. Young Indians need green skills. “The tech boom of the 1990s made engineering aspirational; net zero needs a similar movement,” he says. Companies must start prioritising sustainability literacy in hiring. Even small shifts in recruitment can spark systemic change.

India has the opportunity to leapfrog into a low-carbon future. But that requires political will at home and credible support from abroad. The money needed today is the cheapest it will ever be. Every year of delay will drive up costs. For a nation of 1.46 billion, time is the one resource it cannot afford to squander—because the longer India waits, the narrower its options will become.