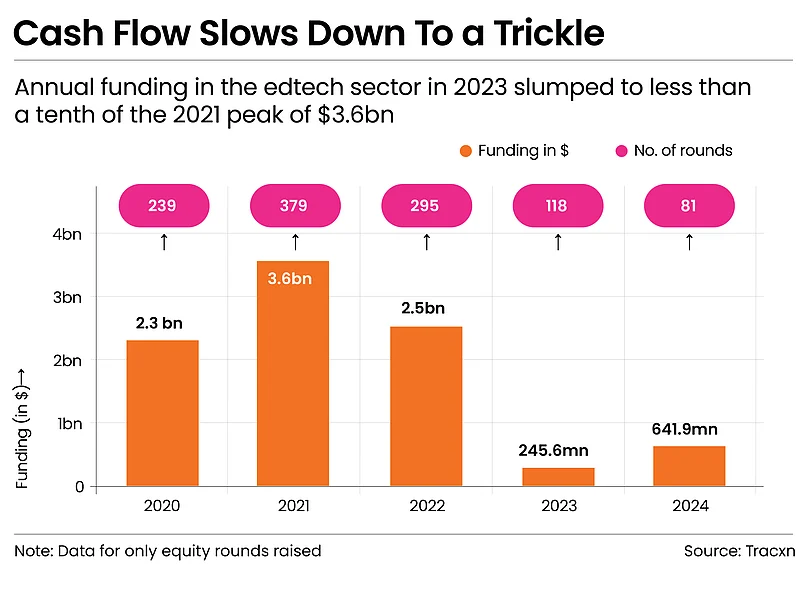

The last time an edtech start-up became a unicorn was in June 2022. India had 97 start-ups with a valuation over a $1bn then. The country now has 110 of those. But there’s hardly any edtech contender in sight.

Things were very different a few years back. As the pandemic restricted children to homes, edtech platforms boomed. For a while, their meteoric rise signalled that online education would help students leapfrog the traditional barriers of accessibility and infrastructure.

Then came Byju’s fall from grace.

What followed were allegations of mismanagement of funds. Billions of dollars evaporated from the company’s balance sheet.The reversal of Byju’s fortunes was a cautionary tale for edtech start-ups, but also a sign that not all was well within the sector. Many start-ups in the sector had tried to replicate Byju’s sales machinery. As sales went up, so did projected revenues and valuations.

Following the loss of investor confidence after the Byju's debacle, hundreds of edtech start-ups had to shut shop and lay off tens of thousands of employees in the past three years.

“Investors have definitely become more cautious of investing in edtech. In the past 1–1.5 years, I’ve observed a growing demand from investors for detailed insights into outcomes. They now give a greater emphasis on measurable success, including the number of students achieving their goals and app engagement rates,” says Vardaan Gandhi, co-founder of another edtech start-up Exampur.

Difficult Questions

However, many students aren’t opening these apps anymore.

Edtechs are trying to adjust to the new reality. But the going has been tough. For instance, the edtech company Physics Wallah, which already operates 120 offline centres, is expanding its network by adding another 30 for the upcoming academic year—a costly affair compared to onboarding users on an online platform. It comes as no surprise then that the company’s loss ballooned from Rs 84 crore in FY23 to Rs 1,131 crore in FY24.

Physics Wallah co-founder Prateek Maheshwari says the company’s offline classrooms are tech-enabled, helping provide a seamless learning experience. Alongside, the company focuses on a hybrid classroom model, often referred to as the two-teacher system.

As the pandemic-induced spike in online coaching wore off, so did the allure of online classes. Parents and students were looking for educational outcomes

“In this set-up, star teachers deliver live lessons and interact with students, while assistant teachers provide in-classroom support and facilitate live communication,” adds Maheshwari.

In 2022, the world of education took another unpredictable turn with the launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. Soon, students were using the tool to write essays and do their homework. Amid the return to offline models of education, layoffs and restructuring, edtech platforms now had to face the existential threat from artificial intelligence (AI) that helped students with homework and online tutoring.

Take the case of US-based edtech platform Chegg whose stock price has plummeted 95% since the launch of ChatGPT.

In an earnings call, company’s chief executive, Dan Rosensweig, grudgingly admitted, “We now believe it’s [ChatGPT] having an impact on our new customer growth rate.”

In the US, the Pew Research Centre estimates that one in five teens who have heard of ChatGPT use it for schoolwork. It can't be too different for India, which is ChatGPT's second-largest market with 9.08% of its 180mn users.

Experts point out that coaching classes took the worst aspects of traditional schooling—grouping a large number of students in a classroom to passively listen to lectures—and amplified them.

In contrast, the right model in the sector would have to involve students learning from one another and teachers, with technology serving as an enabling tool.

So far, edtech has been unable to do it. And billions of dollars of cash have not been sufficient for star companies in the sector to survive.

As caution persists in the sector, there is a case to be made for founders of edtech start-ups focusing on sustainable growth instead of cash burning. While one Byju’s cannot define a sector, there is hope that overall sentiment will change. And as AI becomes ubiquitous in education, all eyes will be on how the sector transforms in the long run.