The first wave of Korean migrants to Japan arrived at the turn of the twentieth century. They came in search of economic opportunity. The Japanese economy was industrializing fast, education was improving, and jobs were aplenty. Compared to a life in poverty on the Korean peninsula, Imperial Japan offered attractive prospects. Among the thousands who took the 11-hour journey across the Tsushima Strait, where a Japanese fleet of steel battleships annihilated the Russian navy in 1905, was a chippy teenager by the name of Son Jong-gyeong.

Masayoshi Son’s grandfather arrived in 1917 in Kyushu, the western island in the Japanese archipelago which juts towards the Korean mainland as Cuba almost touches the southernmost tip of Florida. Imperial Japan was the dominant power in the region, having triumphed in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894‒5 and the Russo-Japanese War in 1904‒5 and having annexed Korea in 1910, reducing its neighbour to the status of a colony. Born in 1899, the teenager lost his father when he was only four years old. Soon afterwards, the Japanese military seized the family farm and turned it into an airstrip.

Although Son Jong-gyeong came from a peasant’s family, he claimed to belong to the Yangban class, which oversaw Korea’s agrarian bureaucracy and disdained all forms of business and commerce. The more refined Yangban exemplified the Confucian ideal of ‘scholarly official’, practising calligraphy and traditional herbal medicine. When the Japanese annexed Korea, they abolished the Yangban class, but the Son family clung to its status. Masa’s father later joked that the family’s aristocratic lineage had in fact died out many years earlier. His family was more ‘Yaban’: less educated, more patriarchal, dismissive of women, and prone to vicious infighting.

Grandfather Son’s first job was at a coal mine in Chikuho, a mineral-rich region known for its extreme summer humidity. As an ethnic Korean immigrant, the rail-thin teenager found himself in a legal no man’s land. He was a subject of Japan’s empire and therefore a Japanese national; but he was not entitled to the status of Japanese citizen. to blend more easily into his workplace, he followed common practice and assumed a Japanese family name: Yasumoto.

Then as now, living under an assumed identity was the easiest way to avoid discrimination. Japanese employers preferred that Korean immigrants adopt names deemed pronounceable by main- landers. Aliases appeared regularly in newspaper reports of crime incidents or death notices. But the blurring of Japanese names and Korean identity was a false assimilation. In an island nation where blood and culture cut deep into the national psyche, Koreans remained victims of systemic prejudice which at times tipped into mass violence.

On 1 September 1923, an earthquake measuring 7.9 on the Richter scale devastated Tokyo, the port of Yokohama and surrounding prefectures. The Great Kanto Earthquake claimed more than 100,000 lives, many incinerated in firestorms, and led to a breakdown in law and order. When rumours spread that ethnic Koreans were poisoning the wells, raping women and stoking the movement for Korean independence, mayhem ensued. Vigilantes rounded up the Koreans (along with ethnic Chinese and Japanese socialists) and massacred them using guns, swords and bamboo sticks. the final Korean death toll was between 6,000 and 10,000.

By now grandfather Son, who had little appetite for manual labour, had run away from the colliery to become a tenant farmer in tosu, a nearby railway hub. Heading towards 30, he was an ageing bachelor desperate to find a partner and start a family. He alighted on 14-year-old Lee Wong-jo, a Korean immigrant less than half his age. Son was a brutish character with a melodramatic streak. He threatened to kill himself unless Lee’s parents consented to his plans for marriage. Eventually they relented, the union was tied, and Lee Wong-jo bore two children, both girls with Japanese names, Tomoko and Kiyoko. the Japanese economy was powering ahead and the Son family could finally look forward to a better life. In 1936, Masa’s father Mitsunori was born, the third sibling in a family which would grow to seven children.

In the 1920s and 1930s, as the world spiralled into depression and instability, Japan’s leaders embarked on an increasingly frantic quest for control over the markets and resources of Asia. the Great Empire of Japan spread like a pool of blood. (On Japanese maps the empire was always coloured red.) Six years after the takeover of Manchuria in 1931, the Imperial Army invaded China and ran amok, committing arson, looting, rape and the mass murder of Chinese civilians. On 7 December 1941, Japan’s surprise attack on the Pearl Harbor naval base – part of a strategy aimed at seizing control of the southern reaches of Asia and the Pacific – was a monumental miscalculation. President Franklin Roosevelt finally had his casus belli and the US entered the Second World War, with cataclysmic consequences for Japan.

During the war, Japanese authorities bribed, intimidated and press-ganged Koreans young and old from the Korean mainland to join the armed forces. Koreans worked alongside prisoners of war and women in the coal mines. As forced labour, they were starved of food and medical treatment, left to rot in a ‘hell on earth’.

Bookmarked

Take a look at what’s new in the business section of Amazon’s bookshelf

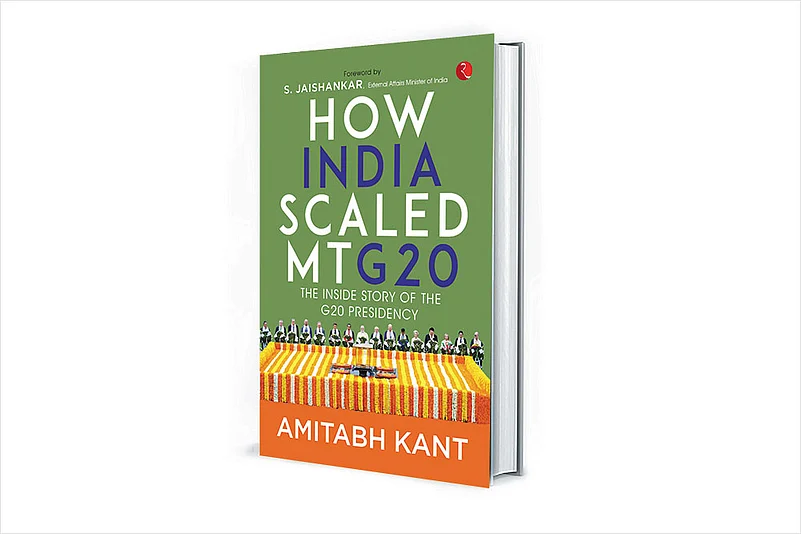

How India Scaled Mt G20: The Inside Story of The G20 Presidency

Amitabh Kant

Published: January 2025

This is an insider’s account of negotiations ranging from climate action to digital transformation.

The Trading Game

Gary Stevenson

Published: February 2025

It is a financial memoir that raises profound questions about who runs the financial markets. It is the author’s account of how he became Citibank’s most profitable trader.

Employment Is Dead: How Disruptive Technologies Are Revolutionizing the Way We Work

Deborah Perry Piscione and Josh Drean

Published: January 2025

With the use of disruptive technologies and decentralised work models increasing, traditional employment models are becoming outdated. The book reveals how organisations can adapt to the evolving landscape of work.

Chhaunk On Food, Economics and Society

Abhijit Banerjee

Published: November 2024

Chhaunk uses food to talk about economics, society and India. Banerjee makes connections between unrelated themes such as between savings and shami kebab or between women’s liberation and the Bengali dish of ghanto.