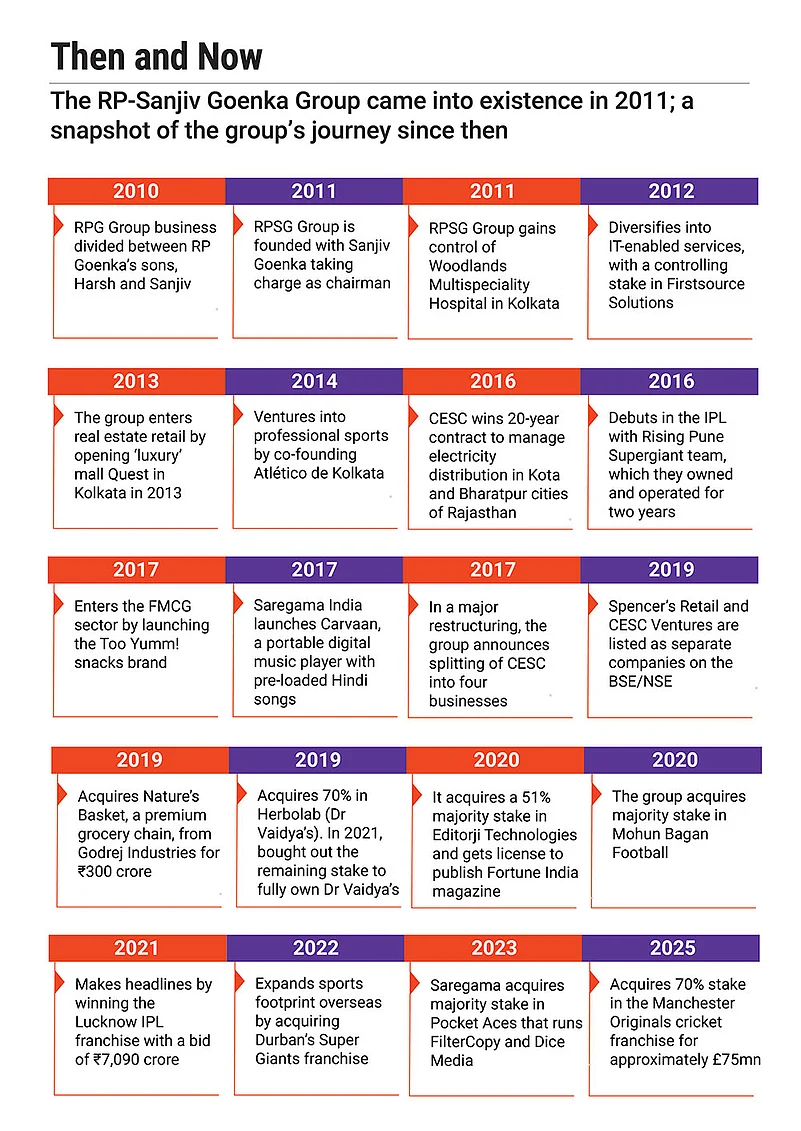

A pall of darkness hung over Calcutta (now Kolkata) in the 1980s. Popularly called “load shedding”, power cuts stretched for hours, and CESC, the city’s main electricity provider, was seen as a symbol of dysfunction. It was in this chaos that a young Sanjiv Goenka made an unlikely bet.

Then in his late 20s, he quietly acquired shares in the beleaguered utility, keeping it from his father, RP Goenka, India’s original takeover tycoon.

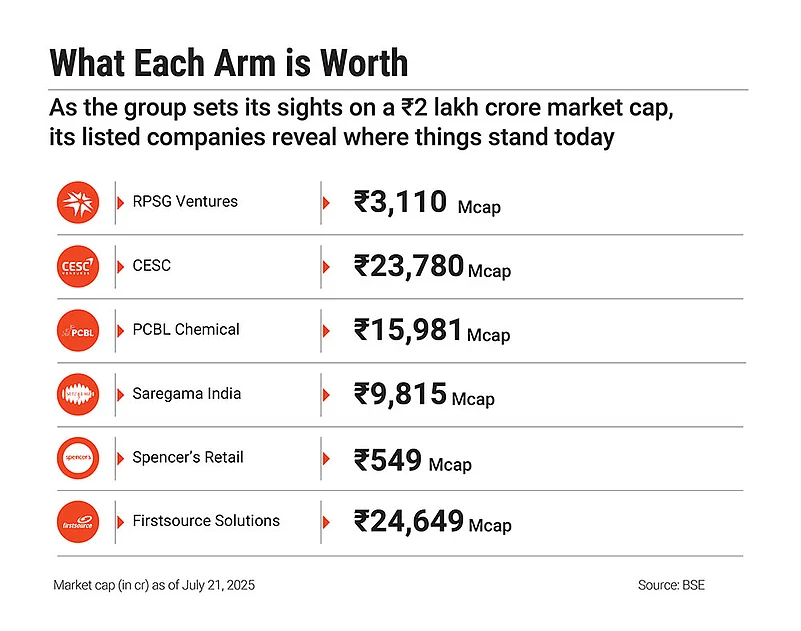

The story has become a family legend. RP Goenka was so rattled he skipped meals for two days, until his wife intervened. But the gamble paid off. CESC became the anchor of the RP‑Sanjiv Goenka Group, now a ₹75,000-crore diversified empire.

DNA of Difficult Bets

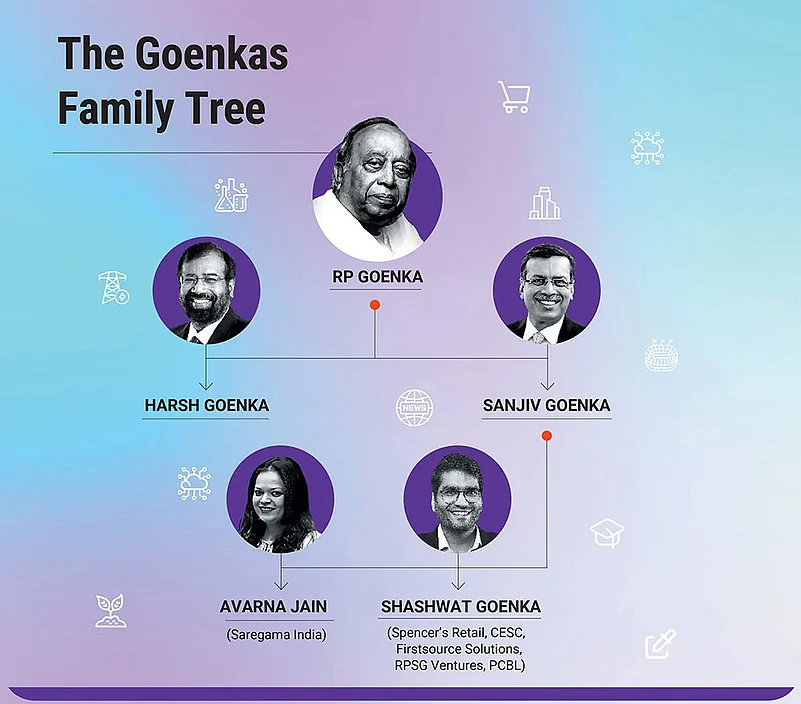

That audacity is part of the family DNA. Decades later, it is Sanjiv Goenka’s son Shashwat who is writing the new playbook. In 2013, at just 23, fresh out of The Wharton School, he took charge of Spencer’s Retail, a business that had clocked losses of around ₹200 crore in 2012–13 and was up against deep-pocketed e-commerce rivals. The turnaround didn’t come overnight. The pandemic nearly scuttled early gains.

But Shashwat didn’t blink. In January 2025, after nearly six years of course corrections, Spencer’s reported earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) breakeven.

The strategy wasn’t a sleight-of-hand trick. It required pruning underperforming stores, doubling down on high-margin formats like gourmet retail and quick commerce, and instilling tighter controls. “You really need to understand what’s going to work in the future for each of the business lines and if you can’t be the first mover, then at least be [among] the early movers to take that advantage,” he says.

His resolve also shows in the Naturali story. When first launched during the pandemic, the group’s personal-care venture flopped, and most would have written it off. Shashwat didn’t. He rebooted the brand as digital-first with revamped pricing, packaging and positioning.

The instinct to keep iterating until the model fits is core to the Goenka approach. Whether it was CESC, Spencer’s or Naturali, they don’t shy away from hard choices.

“The RPSG Group has indeed demonstrated tenacity in its business ventures. For Naturali, the brand’s relaunch with a digital-first strategy has yielded positive qualitative indicators…However, Spencer’s continues to face significant financial challenges,” says Vinit Bolinjkar, head of research, Ventura, a brokerage.

Legacy to Leadership

Shashwat’s leadership is analytical, collaborative and quietly disruptive. Like his grandfather, he’s willing to enter unfamiliar sectors. Like his father, he’s comfortable staying the course through cycles.

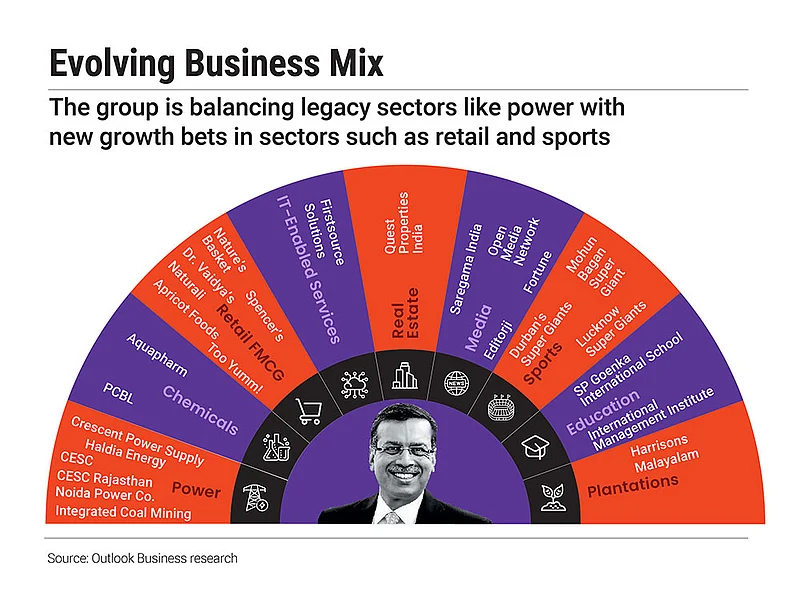

Under his watch, the group’s consumer-facing pivot has accelerated. Too Yumm!, Evita, Naturali and other brands are being built from scratch. Meanwhile, Firstsource Solutions, the group’s business process outsourcing (BPO) arm, has been repositioned to become AI-first, with its ‘unBPO’ model aiming to redefine outsourcing itself.

At the same time, legacy businesses like CESC and Phillips Carbon Black (PCBL) continue to provide the group with steady cash flows. Together, they give Shashwat breathing room to invest in long-horizon ventures like renewables, where the group has committed about ₹8,900 crore for 3.2GW of capacity.

Shashwat’s leadership is analytical and quietly disruptive. Like his grandfather, he’s willing to enter unfamiliar sectors. Like his father, he’s comfortable staying the course through cycles

But those bets come with complexity. Ratings agency Icra has warned about the high leverage and refinancing risk tied to these investments. “The capex plans are large and will expose the company to execution risks associated with land acquisition, right of way and transmission infrastructure;” Icra said in a June 2025 report.

However, Icra noted that CESC has a strong liquidity buffer, with ₹4,042 crore in cash and liquid investments as of March 2025.

Spencer’s and the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) portfolio are still in scale-up mode. Firstsource’s transformation, while bold, is still in early stages and fraught with operational unknowns. While early-stage consumer businesses take time to mature, the group’s diversified base allows it to take risks.

Still, managing capital allocation remains a fine balance for the group. RPSG Ventures, which houses the group’s consumer brands, posted a consolidated loss of ₹49.04 crore in 2024–25.

In its April 2025 report, financial-services firm Emkay Global said the group is entering a new growth cycle, driven by ₹50,000 crore in capex over the next 3–4 years and a sharper focus on value-added, higher-margin businesses. It noted that while some ventures will take time to deliver, the group’s disciplined merger and acquisition approach, conservative stance on leverage and improving operational culture position it well for long-term value creation.

Early in his career, Shashwat helped spearhead a group-wide performance transformation, aimed at infusing sharper financial discipline and cross-vertical coherence into the conglomerate’s legacy structure.

“What’s changed is the role of data,” he says. “Decisions are far more analytical, about where to allocate capital, what ROCE [return on capital employed] to expect, and how each move fits the broader portfolio.” His decision-making process is methodical. In group reviews, he encourages contrarian thinking but demands accountability.

The rise of start-ups has unsettled even legacy players across sectors, and the RP-Sanjiv Goenka Group is no exception. Nowhere is this disruption more visible than in the FMCG segment, where nimble, digital-first brands have started to chip away at traditional retail strongholds.

Shashwat doesn’t dismiss this threat. Instead, he’s adapting to it. “In FMCG, we’re a start-up ourselves. Same with renewable energy. We’re starting out,” he says. That means acting like a start-up: lean, responsive and willing to fail. “We’re doing what start-ups do, including raising funds,” he adds. His strategy isn’t just to compete with new age disruptors, but to learn from them, especially their ability to scale quickly and with discipline.

Building for Tomorrow

Shashwat encourages sharper decision-making and a culture that values speed, agility, ownership and outcomes.

That urgency extends to technology. AI, he insists, is a non-negotiable. “I think AI is something that you have to look at to do things better. If you don’t, you will be irrelevant,” he says.

The group is mapping AI applications across functions, aiming for deep, practical integration. In manufacturing, it’s being deployed for predictive maintenance; in retail, for demand forecasting; and in BPO, to reinvent service delivery itself.

Today, the group’s future rests on four key pillars: renewables, IT services, chemicals and consumer brands. Each holds promise. Each is also laced with risk

Firstsource’s unBPO initiative is especially ambitious. It seeks to replace legacy BPO models with domain-led, AI-integrated, outcome-based operations. It’s a high-stakes pivot.

“It [unBPO] puts Firstsource on a favourable trajectory but only if the model withstands operational scrutiny. In a climate where economic caution competes with digital urgency, what enterprise buyers want is auditability, flexibility and performance consistency,” says Sanchit Vir Gogia, chief executive and chief analyst, Greyhound Research, a technology-consulting firm.

Beyond tech, Shashwat appears alert to the unpredictable forces reshaping global businesses. “Geopolitical changes have always been part of history and will continue to be so,” he says. “The key is to identify and seize opportunities within that uncertainty.”

Whether it is policy shifts or digital disruption, his strategy is rooted in agility and foresight. His understanding of the Indian consumer also informs group strategy. With 70% of India under 35, the demand for experience-driven products is soaring.

This explains the group’s philosophical shift from business-to-business to business-to-consumer. “Being consumer-facing is a mindset. It’s industry agnostic,” Shashwat adds.

While legacy businesses like PCBL export to markets such as Europe and the US, the larger ambition is to build global brands from India. The consumer arm may be small now, but it could shape the group’s identity over the next decade.

Acquisitions remain on the table, but he’s equally open to building from ground up.

Future Tense

In India Inc, succession rarely comes easy. And RP Goenka took no chances, dividing the empire between his sons while still alive.

Today, the group’s future rests on four key pillars: renewables, IT services, chemicals and consumer brands.

In power, CESC remains a reliable contributor. But it lags its peers in both return metrics and expansion agility. Torrent Power and Adani Energy have outpaced CESC in returns on equity and scale.

Gujarat-based Torrent Power operates on a more capital-efficient model by relying heavily on franchise-based distribution and limiting its investments in generation assets. This asset-light approach boosts its ROCE.

As per financial-data platform Screener, CESC’s ROCE stood at 10.9% in July 2025, compared to 15.9% for Torrent Power and 22.5% for Adani Power.

In retail, Spencer’s now faces an aggressive quick-commerce wave. The group’s newly launched quick-commerce brand Jiffy faces competition from Zepto, Blinkit and Swiggy Instamart, which have reshaped last-mile expectations. Spencer’s bet on gourmet formats and premium offline stores will also need to evolve.

In music, Saregama’s iconic catalogue has driven steady growth. But the rise of AI-generated content poses new risks. As music gets commoditised, traditional rights-based monetisation could erode.

The group’s foray into sports with Lucknow Super Giants, Mohun Bagan Super Giant and a new investment in Manchester Originals (a cricket franchise), adds another layer of ambiguity. Visibility is high, but so are the costs; and the return metrics are still hazy.

For Lucknow Super Giants, the group expects the operating leverage will kick in once the broadcasting rights are re-bid in 2027. None of these are deal-breakers. But they’re real. And they will test whether the Goenka instinct, to bet on tough businesses and stay the course, can weather a more volatile world.

As Shashwat puts it: “From a performance standpoint, we’ve scaled sharply. The group’s market cap has risen from ₹3,000 crore (in early 2010s) to nearly ₹80,000 crore. Profitability is in double digits.”

Shashwat seems ready. He speaks like a builder, who is aware that legacy without results is just nostalgia. The challenges are mounting. Capital-intensive bets. Tightening margins. New age rivals. But then again, ease was never part of the Goenka playbook.