Around 50 major oil and gas companies signed the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter at COP28, pledging to accelerate decarbonisation in the industry. The clauses in the charter include ending routine flaring—where natural gas from oil production is wastefully burned instead of being conserved—and achieving near-zero upstream methane emissions by 2030.

Methane emissions account for 25% of the global warming today. A potent greenhouse gas, it stays in the atmosphere for around 20 years and is 80 times more harmful than carbon dioxide, making it a major threat to climate stability. Despite heightened awareness and initiatives worldwide, its level remains stubbornly high, warranting enhanced mitigation efforts.

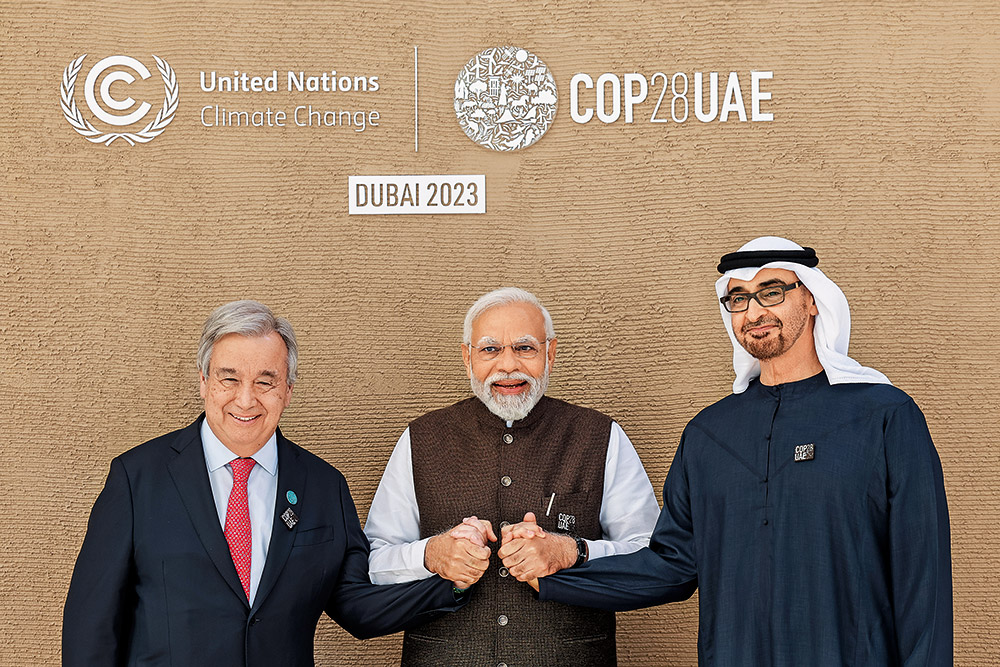

Making the Survival Pitch

India, the fourth-largest methane emitter in the world, has for long resisted the pressure to commit to targets for reducing its methane emissions, its central argument being that any effort to cut down on the greenhouse gas will affect its agriculture and livestock sectors. The agricultural sector in the country accounts for 61% of its total methane emissions, surpassing the energy (16.4%) and waste (19.8%) sectors, according to the International Energy Agency’s Global Methane Tracker 2022.

The Global Methane Pledge, led by the United States and the European Union, initiated at COP26, boasts more than 100 participating countries aiming to collectively reduce methane emissions by at least 30% below 2020 levels by 2030. India had refused to sign this pledge as well.

The government has maintained its narrative that methane gas emission controls will directly impact the poorest strata of the economy. In December 2021, it stated that for a country like India, methane emissions were “survival emissions and not luxury emissions”.

Supporting this stance, Sundeep Nayak, former director general of National Productivity Council and managing director of National Cooperative Development Corporation, says, “India has low cumulative and per capita emissions. The developed world should aim at zero luxury emissions and its net-zero commitments should be based on survival emissions.”

Clock Ticking for India

While India has managed to keep itself out of the methane debate so far, it is just a matter of time before the country hits a dead end in its climate negotiations on the issue. And policy makers are aware of that.

Suneel Pandey, director, environment and waste management division at TERI, a research institute specialising in energy, environment and sustainable development, feels that India needs to do more. “Uncontrolled methane emissions happen from poor management of food waste and other biodegradable waste. For cities, there is a need to improve segregation at source and ensure that biodegradable waste is managed at the ward level itself preferably by feeding it to biogas plants.”

Zerin Osho, director, India Program at the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development, feels that while India has not signed the charter of world’s top oil and gas firms, it will be difficult to avert the pressure. “The signatories do not include any Indian companies,” she says, as she observes that the charter sends a very strong market signal to all oil and gas companies around the world that they too will have to do their bit.

The country is taking domestic measures to address methane emissions, particularly in agriculture, its biggest methane emitter. The National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture has been working on climate resilient practices like reducing methane emissions in rice production. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research has developed technologies for reducing methane emissions from rice. The Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying promotes balanced ration to bring down methane emissions from livestock. The Gobardhan scheme under the National Livestock Mission focusses on waste management to cut down methane emissions.

Since 60% of the methane emissions come from the agriculture sector, a lot is riding on the government’s crop diversification plan. India is promoting production of millets over rice as paddy farming accounts for about 10% of global methane emissions. According to news reports, the Uttar Pradesh government has plans to replace around 17% of the area under paddy cultivation with millet and oilseed production in the coming years. It is the second largest producer of rice in the country.

India is betting big on its investment in technologies that help reduce methane emissions in agriculture, but it is long road ahead for a country where more than half the population depends on agriculture for livelihood. Meanwhile, to show its commitment to the larger cause of climate action, India will need a more comprehensive strategy to curb methane emission sooner rather than later. The clock is ticking.