Cocky. Confident. Brash. Brilliant. Bhavish Aggarwal is all of these. And he is more. At first glance he is a man on the cusp of midlife. His pitch-black hair seems to have been brushed back aggressively, revealing a growing forehead untouched by frown lines. He loves dogs. They are the only beings with unbridled access to him, in his office, in meetings or at home.

When you speak to him, he looks straight into your eyes. In his voice there is assertion. In his demeanour a worrisome paucity of doubt. Until recently he could be spotted wearing a T-shirt or even a suit. But not anymore. The 39-year-old has recently taken to the kurta and is at ease in it. It helps that it makes a statement.

But making a statement is not where Aggarwal is willing to stop. Not even at making a mark. Born to doctor parents, brought up in business-friendly Ludhiana and educated at the premier Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay, Aggarwal belongs to that sliver of the Indian middle class that has seen lives and lifestyles improve drastically since the liberalisation years. Thus, fresh out of IIT, when he secured a research role at Microsoft, it wasn’t enough for him. He quit within two years and started building Ola with his IIT-batchmate Ankit Bhati.

App-based cab hailing was new to India in 2012. Uber had been conceived only a few years prior in the US and had no plans of coming to India at the time. Ride hailing was not seen as the big business it has become in a country with patchy internet and limited access to smartphones. Yet in four years, Ola Cabs became a unicorn. In an interview with Bloomberg TV in 2015, the then 29-year-old Aggarwal said, “Our [Ola Cabs’] vision is that people won’t [need to] own cars.”

That is one of two things that strike you about Aggarwal when you speak to him even 10 years later—he loves grand narratives. While a decade ago he dreamt of replacing the self-owned car as a means of transport, today he wants to lead an electric vehicle (EV) revolution that will propel India’s rise as a manufacturing power.

“Ola Electric is the vanguard of the EV revolution,” he tells Outlook Business in an interview. The other striking feature is his laughter. A man often characterised as mean, rude or overbearing laughs a hearty laugh and often bursts into peals that betray an innocence lost on the more worldly wise, disenchanted souls.

Basic Instinct

His wife Rajalakshmi, when asked nine years ago what distinguishes Aggarwal from others, had a one-word answer: perseverance.

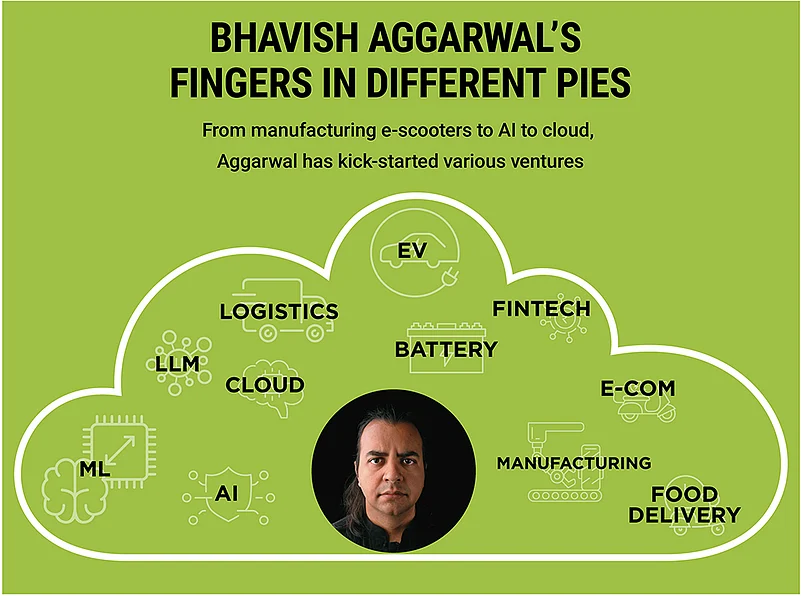

Others who know him closely often describe Aggarwal as “restless” and “always in a hurry”. Soon after he started Olatrip.com—his first venture—and failed to “sell a single trip”, he switched to Ola Cabs. Just as the cab venture took off, he attempted to expand into food and grocery deliveries. Both projects bombed. In 2017 Aggarwal started Ola Electric—his EV and battery-manufacturing venture and six years later he founded Krutrim, an artificial-intelligence (AI) venture.

“Move fast, break things” was the Zuckerberg-ian mantra in Aggarwal’s early days, and move fast breaking things he did. And with no second thought, he asserts. While many business leaders look at him as a man seeking to do everything, everywhere, all at once, risking it all, Aggarwal maintains he does his due diligence and that his risk appetite “comes from conviction, from a sense of purpose”. His risk analysis in one stroke aligns and differentiates him from the many phenomenal mavericks who have come before him, and vanished.

Proving Naysayers Wrong

Aggarwal is not one to take a slight lying down. Nor is he above being a provocateur. When Uber came to India in 2013 there were strong murmurs that Ola would have to merge at SoftBank’s insistence. SoftBank was invested in both companies and did not want the market share split. A similar deal had taken place in China where Uber and local major Didi Chuxing merged. But Aggarwal was adamant, unwilling to cede an inch. His business threatened, he cried foul. “It’s a very unfair playing field for Indian start-ups,” he said.

Years later he has matured to think of that episode as a lesson. “In our journey we have had investors in a different direction for the company’s future versus me. We have done down rounds. Valuation for me is just a number. I believe in value creation,” he says. “No one thought Bhavish could win against Travis Kalanick [former Uber chief executive], but Bhavish is a fighter,” a source close to both Aggarwal and SoftBank says.

And he has kept fighting. His foray into automobile manufacturing—a space controlled by legacy sharks—invited ridicule. A particularly silly wrangle broke out when Rajiv Bajaj, the managing director of Bajaj Auto, said, “Champions eat OATS for breakfast” referring to EV-makers Ola Electric, Ather, Tork Motors and SmartE. Aggarwal, in a sillier comeback, said, “I put ICE cubes in my drink,” where ICE meant manufacturers of internal combustion engine vehicles.

Embarrassing squabbles aside, Aggarwal is hell bent on proving naysayers wrong. The bigger the naysayer the better. “Legacy players used to look down on Bhavish, ridicule him, think of him as a renegade. Now they are almost jealous of him,” says Vivek Wadhwa, an Indian American tech entrepreneur and academic. He adds: “I call him Elon Musk without the character flaws.”

Musk’s name crops up often when one speaks of Aggarwal. And Aggarwal too doesn’t miss an opportunity to speak of Musk, often to just one-up the world’s wealthiest social media junkie. Like when he said Musk should “try something new for a change” in a joking bid to say that the Tesla-founder was following his example with Krutrim to wade into the AI space. Is the referencing organic or carefully curated to make it to the news? One cannot say conclusively.

What one can say with a certain degree of certainty is that Aggarwal has an intrinsic ability to extrapolate anecdotes to serve his narrative. Like he did when LinkedIn identified him with the gender-neutral pronoun ‘they’ instead of ‘he’. Aggarwal took to X to rant against what he called an attempt by the Microsoft-owned social media platform to “impose a political ideology”.

If his tirade had just been the outpouring of outrage by a tech-entrepreneur from the global south against ideological impositions, one would understand. But what he did next was more revealing. He announced that Ola would move out of Microsoft’s cloud-computing platform Azure and into its own Krutrim cloud. He then invited other Indian companies to do the same.

Since then, his narrative dexterity has matured. He now identifies the dominance of Google, Meta and Microsoft as ‘techno colonialism’ and thinks of himself almost as an enterprising freedom fighter. “India generates the largest amount of digital data in the world, but all of it is sitting in the West. And then they take our data out, they process it into AI and then bring it back and sell it in dollars to us. It’s the same East India Company all over again,” he says. His critique does not account for the nuance that much of his initial funding came from global investment companies.

Moneyball

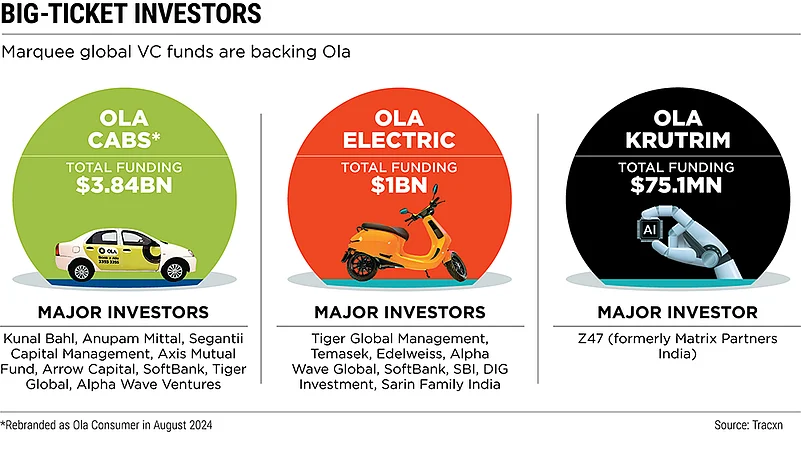

Persistence and storytelling aside, a mundane skill that keeps Aggarwal ahead is his ability to keep the funds flowing. He has delivered three unicorns in 14 years in three distinct segments. Ola Cabs (now Ola Consumer) raised $3.84bn in 25 funding rounds. Ola Electric raised $1bn in 14 rounds before its public listing and became a unicorn before the first scooter had sold. Krutrim raised $75mn in four rounds but has already cracked a $1bn valuation becoming the fastest unicorn in Indian history.

Aggarwal now positions western technocracy as techno colonialism and likens tech majors to colonial enterprises of the past.

Aggarwal has had big investors like Tiger Global, SoftBank and PeakXV (formerly Sequoia Capital India) backing him from the beginning of his journey. And that has allowed him to acquire TaxiForSure and run experiments such as Ola Cafe and Ola Play.

SoftBank’s decision to stay with Aggarwal despite the tensions during the Uber merger talks phase is a testimony to his appeal. “The decision to invest in Bhavish was made by Masayoshi Son [SoftBank chief executive]. He saw a resolve in Bhavish to succeed,” says Alok Sama, a former president of SoftBank Group International and its ex-chief financial officer.

The abiding faith investors have reposed in Aggarwal, however, is of limited use to him now that Ola Electric is in the public markets. Stock markets seldom show unquestioning faith in the genius of an individual entrepreneur and typically have a low-risk appetite. Will that rein in the perpetual risk-taker-disruptor? Aggarwal doesn’t think so: “Public markets want to understand risk. They are not averse to risk.”

It was a degree of caution, observers say, that influenced Aggarwal’s decision to peg Ola Electric shares at a relatively low price of Rs 72–76 a piece. Aggarwal was quoted saying that he wanted to appeal to “the entire investor community in India”.

While to some that might seem the public market’s way of tempering a maverick, Aggarwal has always believed in the volume game as in shares just as in his products. “Bhavish follows the philosophy of India’s old-school industrialists. From the get-go he was interested in playing the volume game,” says Shankar Sundararaman, managing director of EV-charging station development company Electrip. And along with playing the volume game, there is a growing realisation within Aggarwal that his company is now a “custodian of the common man’s money”.

Techie at a Factory

When Aggarwal announced in 2020 that he was going to pour in Rs 2,400 crore to build a factory for EVs in Tamil Nadu, many gasped, more sniggered. The world was going through a once-in-a-century pandemic and businesses made the news only because they were shutting down. More importantly, manufacturing in India was seen as the monopoly of legacy players. And the product he was building had little to no penetration.

But Aggarwal proved himself. His ‘future factory’ was up and running within a year. The first batch of Ola Electric scooters started getting delivered in December 2021. In Indian manufacturing this was a huge feat. No other company, at least in recent memory, has managed to stick so close to proposed timelines and deliveries.

But the speed came at a cost. Four months later an Ola scooter burst into flames in Pune. Days later another burnt to the ground in Thiruvananthapuram. A number of fires were reported subsequently.

And people were quick to judge. Social media had a field day mocking an entrepreneur who had dared to dream. The government worried that malfunctions in Ola scooters could put the fledgling EV industry at risk. What no one considered was that innovation in vehicles always comes with risks. But it soon surfaced that Ola Electric scooters were not the only ones catching fire or running into trouble. Data from an automotive industry observer showed that electric scooters made by Hero Electric and Okinawa had higher breakdown rates than Ola Electric in two delivery fleets in 2023.

The initial anxieties did not however faze Aggarwal. He continued his volume play. Ola Electric’s cheapest scooter was priced at around Rs 75,000—40% cheaper than the next electric scooter made by legacy player TVS and around half the price of a scooter made by Ather. Then Aggarwal focused on building the biggest possible distribution network.

Data from brokerage firm Elara Securities shows Ola Electric had more than half the share of the electric two-wheeler market in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Odisha and West Bengal at the end of the last fiscal year. Ola Electric developed 870 experience centres while TVS managed 720 and Bajaj Auto only 250. Within three years, Ola Electric’s share of the market went up from 6% to 35%.

But the superfast expansion is yet to bring Aggarwal any money. Despite dominating the market, Ola Electric’s losses have only mounted, from Rs 199 crore at the end of financial year 2021 to Rs 1,578 crore on March 31, 2024, a jump of around 700%. In April Ola Electric’s market share shot up to 54%. Yet its losses kept rising.

This is because making EVs continues to be expensive and making an electric scooter actually bleeds money. More than a third of components have to be imported from China which is difficult when Sino-India relations are strained.

But Aggarwal is working on a transformative workaround that gives him a significant edge over the competition: manufacture all component parts. “The cost of the battery is 30–40% in an EV. In the ICE era, companies that were successful had complete control over the engines, because that was the most important part of the car. Therefore, in the EV era, those companies that will make the battery-cell technology themselves will become global leaders,” he says. And it is with this in mind that he is working on the Bharat cell—the indigenously made batteries he seeks to introduce by early 2025.

Lonely Walk the Brash

The past decade is evidence that Bhavish Aggarwal can do almost whatever he puts his mind to. The one thing that has tripped him is people management. Aggarwal has struggled to keep his flock together. His friend and co-founder Ankit Bhati quit Ola Cabs’ parent company ANI Technologies in 2020 after rumours spread that the two had fallen apart after the company’s bid to acquire Foodpanda to rival Uber Eats.

The company denied the rumours.

"Legacy players used to look down on Bhavish, ridicule him, think of him as a renegade. Now they are almost jealous of him. I call him Elon Musk without the character flaws." Vivek Wadhwa, Entrepreneur-academic

In 2022, a Bloomberg report suggested that Bhavish Aggarwal’s “abrasive” behaviour has turned the work culture at Ola Electric “hostile”. While the company contested the claims, Ola Electric’s draft red herring prospectus (DRHP) revealed it had an attrition rate of 47.48% in financial year 2023. While the number is concerning in itself it needs to be judged in context. Start-ups typically have high attrition rates. Paytm reported an attrition rate of 65% the same year and Zomato 41%.

Aggarwal doesn’t think of attrition as a concern and says it is concentrated at junior levels. “The core of our team is strong, and the team is motivated by our mission. We have a lot of junior agents at the front end of the company. This pushes up the attrition rate. As you move up to the corporate level the attrition is low,” he says.

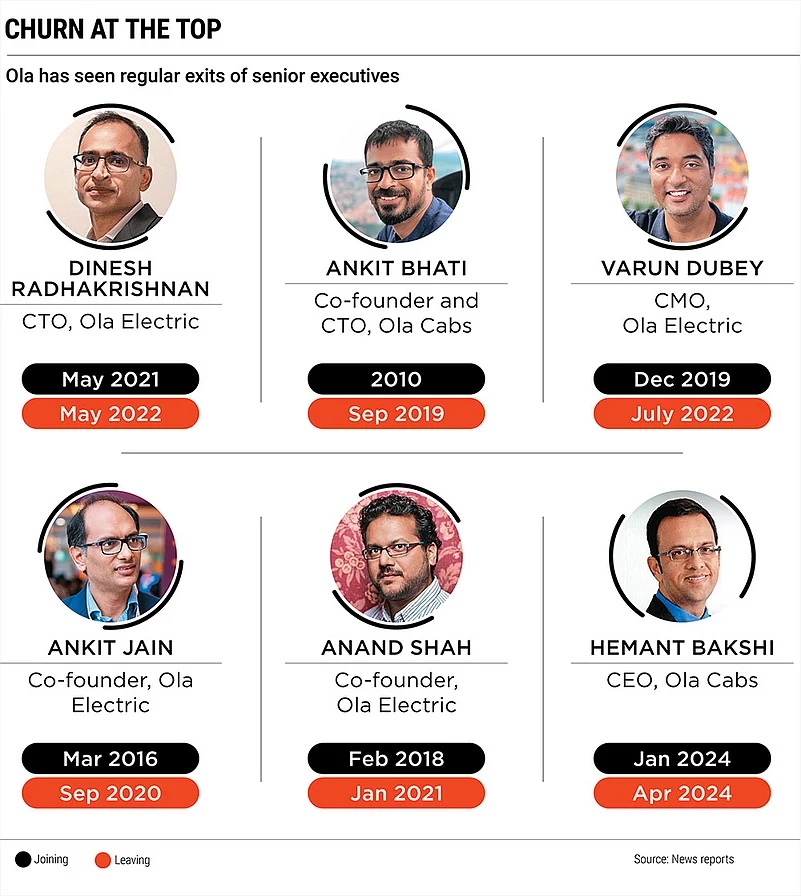

While he believes that, it is also true that the top management undergoes frequent churns. Just this year Ola Cabs’ chief executive Hemant Bakshi and Ola Mobility chief financial officer Karthik Gupta quit the company. At least 13 senior executives have quit the company in the past five years.

“Bhavish’s feedback is in the face. If there is a lack of effort on the part of an individual then there is direct feedback. And it is not sugar coated,” says an Ola Electric vertical head. A former senior Ola executive says Aggarwal’s working style does not suit many who come from seasoned corporate backgrounds.

“In private meetings he would be okay but in meetings involving others he would become closed to ideas and try to be the smartest person in the room. Once he makes up his mind about something it is nearly impossible to convince him otherwise,” adds the former executive.

The vertical head at Ola Electric disagrees with the characterisation. “He is open to feedback. There is 100% room for discussion. You can have endless debates with him on merit. Just that there must be logic in what one is arguing,” he adds.

Testimonies of other former senior staffers paint a picture of a man who does not like to be pulled back by processes. “Bhavish has a tendency to set unrealistic timelines and targets. A senior recruit would come in and if he [Aggarwal] feels they are slowing the company down, they would be asked to leave,” says another former senior staff member who did not want to be named.

But admirers of Aggarwal say it is his aggression that has made his companies scale. Pradeep Kumar, the company’s former global head of finance, gives an example: when the enterprise resource planning system implementation was taking place, the people working on it asked for two years to finish the process. Aggarwal wanted the work done in four months. After a lot of back and forth, the project finished in six.

“Bhavish is not bluffing when he says he works 20-hour days. He backs those he trusts and keeps reminding them that they are there to build something big,” Kumar adds. Kumar’s version is reiterated by another person close to Aggarwal who did not wish to be named. This person says: “He really cares about those close to him. He takes time to get to know them, their families, about the schools their children go to.”

Aggarwal has been open to experiments in human resource management, such as running his Ola Electric plant in Tamil Nadu singularly by women

Disbelief in Balance

The impression one gets is that Aggarwal is obsessed with efficiency, an obsession that gives him speed yet makes him vulnerable to controversy.

He has been troublingly transparent in his belief about work-life balance. He was one of the first business leaders to come out in support of Infosys founder NR Narayana Murthy when he suggested that young people in India should be working 70 hours a week, a comment that earned the pioneer of India’s tech ecosystem a great deal of social media scorn.

Aggarwal has been open to experiments in human resource management, such as running his Ola Electric plant in Tamil Nadu singularly by women. And according to him, the move has made business sense. “Women are very disciplined. They follow all the policies of the workplace. More than men,” he says.

His primary contention with those seeking work-life balance is that he believes this is not the historical moment for such a pursuit: “See Germany, China, Japan...The average Japanese is better off today because the previous generation worked hard. Isn’t the average German proud of where his country has reached because of what the previous generation did?”

He also doesn’t think that the call for work-life balance is a generational demand usually attributed to Gen Z. “I actually feel Gen Z wants a purpose in life. It is incumbent upon us to inspire them,” Aggarwal says.

The decision to invest in Bhavish was made by Masayoshi Son [SoftBank chief executive]. He saw a resolve in Bhavish to succeed. Alok Sama, Ex-president, SoftBank Group International

At the heart of Aggarwal’s philosophy of work are the values and contradictions of 20th century capitalism. He thinks development is a consequence of rising worker productivity and has begun believing manufacturing is the way to achieve development at scale.

Within the grand narrative of India’s rise to “developed nation” status, he sees Ola as a potential force. He feels young people are alienated and can be convinced to work hard. And thus, he says: “This generation is not driven by the need to have a certain salary to de-risk their life, which was my parents’ generation, who focused on roti, kapda aur makaan. There has to be one generation that does tapasya and that is our generation.”

His definition of a generation, however, includes only a singular socio-economic class. The class that enjoyed stable salaried incomes in the 1980s and ’90s and benefited immensely from the middle class-focused opening of the Indian economy where a certain stratum of Indians could become global consumers. His vision would perhaps ring hollow to the thousands of Gen Z who regularly queue up for government jobs or those in the unstable gig work like driving Ola cabs.

Favoured Child of History

An hour-long conversation later Bhavish Aggarwal does not stop for coffee or water.

In him there is a realisation that he is an entrepreneur at a moment in history where they are perhaps the most celebrated of entities in the socio-economic culturescape. In ancient India that pride of place was reserved for saints. In the 18th century the world regarded scientists similarly. The 1900s was the moment of freedom fighters in over a third of the world. This moment of the 21st century is the moment of the entrepreneur—of the man who sacrifices all for the sake of enterprise.

He takes that position seriously, and to his credit, not as performance. His colleague Vishal Chaturvedi, business head of Ola Cell at Ola Electric says, “He is beyond building companies now. Bhavish is thinking about how to contribute to India's journey of development.”

American novelist F Scott Fitzgerald wrote of his protagonist in The Last Tycoon that there are moments in history when “one man appropriates to himself the total significance of a time and place”. Aggarwal, in his brashness as in his brilliance, perhaps does the same in India of the moment. Aggarwal’s ambition may be polarising, but it’s precisely this audacity that has driven his meteoric rise.

In his leadership philosophy characterised by his penchant for risk-taking, Aggarwal is both new and old. He is not a man of abstracts. He has built his empire by taking risks others deem reckless. As he speeds into uncharted territory the question remains: can Bhavish Aggarwal continue to defy the odds or will his audacity, like many disruptors before him, become his Achilles heel?