Vikash Jaiswal can’t hide his excitement. The 40-year-old travelled to Mumbai from Patna 15 years back to try his hand at an unusual career — game development. In Mumbai, he worked with several companies before starting out on his own with Gametion in 2008. It has been a few years in this industry but, over the past two years, there has been a remarkable change.

He launched an online board game — Ludo King — in December 2016. Earlier, he had brought out various browser-based puzzle, racing, and action games but traffic for these games was declining. He turned his attention to mobile-phone games and Ludo King had to wait for eight months to hit the one million downloads milestone on the Google Play store. Today, the rate of downloads has sped up to reach over 200 million — a massive number. “We are the only Indian title to have crossed 100 million downloads on Google Play store,” he says. Since then, he has also brought out Carrom King, the downloads of which have now reached over 10 million.

What really changed in the past two years? There are the obvious reasons. The smartphone penetration increased to a massive 500 million users in India (with 404 million users in 2017 according to Cisco’s Visual Networking Index). Next came the advent of Reliance Jio in 2016, which showered the telecom market with freebies. There was high-speed data available at cheap rates across the country. As per the Department of Telecommunications, data rates fell by 93% and data usage increased 25x over three years.

The Indian gaming market, estimated to be at one billion, had anyway been on the rise over past five to seven years. The number of Indian game publishers rose from 25 to 250, between 2010 and 2017. Prominent names now are Dream11, Nazara Technologies, 99Games, Gametion, Octro, JetSynthesys and Moonfrog.

Though the average revenue per user in India is only $13, as of 2018, it has seen the fastest growth in the gaming markets of the world. India’s average revenue per user (ARPU) has doubled between 2016 and 2018 (according to Newzoo, a gaming/apps data consultancy). And there is still significant headroom for growth. For example, Indonesia, which is mobile-first gaming market similar to India, has an ARPU of $33. According to a report from Newzoo, “If mobile players in India were to spend the same annually as they do in Indonesia, the market could grow to as much as $5.2 billion by 2020.”

Bhavit Sheth, COO and co-founder of Dream11, has been in this industry for 11 years. The credit of introducing fantasy sport — in cricket, hockey, kabaddi, NBA and football — to India goes to him and the other co-founder of Dream11, Harsh Jain. In this format, contestants can build their own teams picked from real sportspeople and decide their playing positions. Points are made based on the performance of the sportspeople in actual games, which could be held the next day. Dream11 commands more than 90% of the fantasy-sport market share.

Sheth has noticed “phenomenal growth” of users over the past year. They added 20 million users during IPL 2018. “In January 2015, we had 300,000 users. Last week, we counted 50 million,” he says. And this is despite Dream11 not being available on Google Play store, due to Google’s policy of not allowing money-in/money-out apps, where you pay for or against an outcome in the game. The game can currently be downloaded from their website and the team is working with Google’s India team to tap into the massive Android market.

Rohith Bhat too has noticed the Indian gamer’s growing interest in multi-player games, which consume a lot of data. He started his company 99Games back in 2008 and built popular games such as Dhoom: 3 The Game, Star Chef and WordsWorth. “Today, Indians are open to playing over network, connecting with hundreds of others,” he says. PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) is a dazzling example. “As a player, you get to see progress of 100 other players, which requires a lot of bandwidth,” says Bhat. Still, it is the most popular mobile game in the country.

The game is so popular in India that even Prime Minister Narendra Modi joked about PUBG addiction in an interaction with young students in Delhi last month. Bhat’s Dhoom: 3 The Game (which is based on Yash Raj Films’ 2013 hit) used to see roughly 200,000 downloads per month a year back. Today that number is one million per month.

He is investing more man hours on the Indian market now. “Since monetisation wasn’t happening here, we were making global games and experimenting with Bollywood games. But we have started building original intellectual property for Indian market now,” he says.

Other gaming biggies and investors are homing in. Dream11’s huge popularity in India caught the attention of world’s largest gaming company, China’s Tencent. It led a $100 million round of funding in September 2018, valuing the start-up at $600 million. Recently, after hedge fund Steadview Capital’s investment in Dream11, the valuation is estimated to be over $1 billion — making it India’s first gaming unicorn. Sheth sees no competition from Tencent’s PUBG. “You play PUBG when you have some time. With fantasy sports you need to schedule it around matches,” he says.

Arpit Agarwal, principal at Blume Ventures, feels that these are exciting times for gaming in India. His fund has invested in four gaming start-ups so far, which include companies such as Mech Mocha, Rolocule, Glamors and Hashcube. “When we invested in Mech Mocha four years back, things were entirely different. One of the key objectives was to build a less-than-20 MB game, today people are building 1.5 GB games. Phones have become more powerful,” says Agarwal.

Slow Profit

Games have become more sophisticated, with investment running into millions of dollars, but monetisation still takes a while.

“Low investment cycle games (which are usually low MB games) have a quick monetisation period,” says Rajan Navani, vice-chairman, MD & CEO of JetSynthesys. That is, if an investment of a few million rupees is made over six months to develop a game, it can be recovered quickly, even within six months. Whereas, a sophisticated game built with a couple of million dollars may need more than 18 months. “Both have a different value propositions” says Navani. For their Sachin Saga game, launched in partnership with Sachin Tendulkar eight months ago, the cricketer’s actual shots were motion captured in the same studio in UK where James Bond’s special effects are done. The game, which clocked 10 million downloads, is available in VR format also. They are continuing to invest in the game, and the company has raised $25 million till date.

Agarwal admits that there is nothing much to show on the monetisation front for them yet. But he is certain that there is an opportunity. “Every person who has enough to eat has an entertainment budget. People are spending on Netflix also. All you need is a pie of that budget,” he says.

Across the world, gaming industry has two monetisation models — advertisements and in-app purchase. Since, most gaming apps sit in the Google Play store, in most cases, Google Ads is the biggest source of revenue for Indian publishers. The massive increase in downloads has caused a surge in their revenue.

Gametion’s Ludo King earns 95% of its all revenue through Google Ads. “Last year we earned $6 million dollars, which was 25x from the year before,” he says. “70% of our users are from India,” he says. The remaining are mostly from Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Tunisia and Iran. Apart from the usual banner-advertising, there is a provision to watch video adverts to get coins in an online multi-player mode. In JetSynthesys’ Sachin Saga, people can watch ads to advance in the game. “Since it is cricket, we also use the real-estate such as cricket pitch and boundary wall to promote companies and brands,” says Navani.

In case of Dream11, Sheth is tight-lipped about the revenue generated by the game, but reports peg it at Rs.1 billion in FY18.

According to industry experts, 80-90% of the publishers’ revenue come from advertising. Whereas, in developed markets, it is the opposite. Around 80% of revenue is generated from in-app purchases. In-app purchases are built into the game. For example, a shooting game can prompt you to purchase points to get hold of an advanced weapon or skip to another level.

Indian games are slowly making their shift to the ‘fremium’ model — where a game can be downloaded for free but additional features will have to be purchased in-app. PUBG, for example, makes revenue from in-app purchases such as various skins, clothes, progression passes and so on. Although their India data has not been made public, it is estimated that it earns 2% of its overall revenue from the country.

Online payments have become more mainstream over the past two to three years with wallets gaining popularity.

Dependency of India-centric games, such as Teen Patti and Rummy, on advertising is minimal. “Eighty per cent of revenue in Teen Patti is from in-app purchases. It indicates that a habit change is underway in Indian market as well,” says Bhat. Teen Patti has 50 million downloads on Google Play store, a 5x increase from 10 million in 2015.

Their game Star Chef, launched three and a half years ago, has done well globally, and makes most of its earnings from in-app payments of users across countries including from the US, UK and Australia. “It has 20 million downloads and the revenue has been Rs.1.5 billion during its life,” he says. In this cooking and restaurant management game, players live the life of a virtual chef — starting with a small piece of land, table area, one cooking station and a few diners. As the game progresses, one can buy more land, hire additional staff and so on with in-app payments. The cost of making this game was between Rs.20-30 million, excluding the marketing cost.

Navani says that in-app purchases in Sachin Saga have seen a “significant growth of 70 to 80%”. “The user has to pay somewhere between Rs.10 to Rs.50 for different offerings, and we have seen people spending several hundred rupees,” he says.

One company in India whose entire model is based on in-app purchases is Dream11. Since it is not on Google Play store, Dream11 can’t count on Google Ads as a revenue stream. But Sheth says that that ads can spoil user experience and they don’t want them on their platform. Upon joining, every user gets 100 credit points with which to buy players and create a team. The player can then choose to join a cash contest. If they win, the money collected is split between the winner and the company. For example, if the total pool comes to Rs.100 between two players, the winner takes Rs.80 and Dream11, Rs.20.

To convince payment gateways, banks and Facebook was a challenge for the company. The founders ran the model through legal advisers. Because money and bidding is involved, a user also went to court. “In 2017, he lost money and claimed this is gambling. The High Court of Punjab and Haryana heard the matter and adjudged that it is a game of skill, and the Supreme Court reaffirmed that decision. It was a shot in the arm for us and after that people have been more willing to work with us,” says Sheth. That’s when Dream11 got MS Dhoni as a brand ambassador, last year.

Since Dream11 is aligned with actual matches, is it a seasonal business? No, says Sheth. “Every month there is a premier league or a T20 series somewhere in the world. We run around 3,000 matches around the year,” he says. Cricket constitutes 85% of the action on the app.

The Dragon Cousin

Indian gamers are similar to their Chinese counterparts who have also evolved as freemium players. Current ARPU in China is a high $112 (equal to that of US). One third of the gamers pay for in-app purchases. Gamers in China pay for advancing to new levels, purchasing virtual products, instant revival of life and privileged access to games. Interestingly, 29% of these gamers do not recall the details of the purchase, which indicates a high level of engagement.

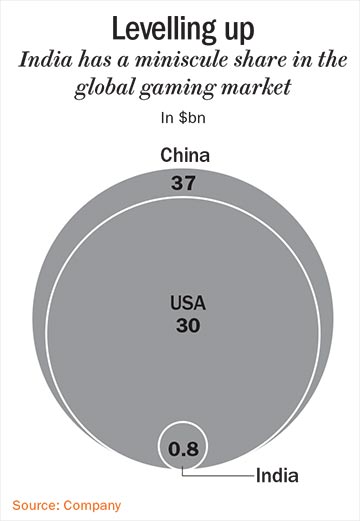

India is advancing in the game but, according to Navani, it is still where China was a decade back in 2007. China was a small market then and it has now overtaken the largest gaming market, the US. China’s gaming market is pegged at $37 billion, the US at $30 billion and India at $800 million. India has only a small share, of 1%, in the global market of $120 billion (see: Levelling up), says Navani.

Mature markets such as the US and Japan have had a gaming culture and industry for decades. But China is one market that the Indian industry can emulate. China has gaming mammoths such as Tencent and NetEase, which not only dominate Chinese gaming, but figure amongst the top globally.

While these gaming majors had started building games by 2007, the real potential was unlocked with the advent of smartphones in China. Even in 2010, six of the top 10 free games and 10 of the top 10 paid games were foreign titles. Today, there is only one foreign title on the topper charts in China.

Indian and Chinese markets share similarities – a large smartphone user base, a significant population of youngsters, a thriving tech start-up/publisher base and users with a preference for free-to-play (F2P) games. But, in India gaming remained a niche activity till smartphones and cheap data became accessible to most Indians a few years ago. China also protected its industry through state regulation, which Indian players won’t get. Navani says, “Unlike China we don’t block outside games, so Chinese games figure in our top 10,” he says.

Our local players are however learning a few tricks from the Dragon Country. Tencent changed the game in China, to top the gaming charts, by buying stake in or partnering with several global players and then localising the games. No wonder, all the top games are Chinese today! Dream11 and Teen Patti are trying the same here. Bhat says, “As Indians we understand cultural nuances better. Before studios from outside start understanding our local nuances, we must build products. That is the race we are in now.”

Other Platforms

While mobile-based gaming is stealing all the limelight, other platforms such as e-sports and PC gaming are seeing fresh traction in India.

E-sports is nothing but a live tournament of celebrity gamers at a venue. In mature markets such as US and China, e-sports events are organised in big stadiums and attract thousands of gaming lovers. The number of e-sports audience, worldwide, has rapidly grown from 86 million to 386 million, between 2015 and 2017. Globally, this is pegged as a billion-dollar market.

India got its first major e-sports league in 2017 with U Cypher, a multi-platform, multi-game tournament, where organisers gave out Rs.5.1 million in prize money. The event was televised on MTV.

Nazara Technologies acquired a majority stake in Gurgaon-based e-sports platform NODWIN Gaming in 2017. NODWIN has the exclusive long-term India rights for global partners such as Electronic Sports League (ESL) and Esports World Convention among others. Ace stock-market investor Rakesh Jhunjhunwala invested Rs.1.5 billion in Nazara in 2017.

Vamsi Krishna, head (consumer marketing) for South Asia at NVIDIA, says, “E–sports is very important as it brings lot of awareness around gaming in the country. Apart from the professional who plays at the league, there are approximately two to three million casual e-sports players in the country and this number is only going to go up.”

But it is not e-sports where this processor company is focusing on. It is focusing on something conventional — PC Gaming, the old gaming parlour way, though in a new avatar. There are 60 million PC gamers in China and there are 150,000 cafes. Even in Vietnam, there are 42,000 gaming cafes. But in India there are less than a 1,000 gaming cafes. “Our strategy is to help this category grow in India. There is limited know-how amongst investor community and we have been organising investors meets to explain all the aspects of a gaming café to them,” says Krishna.

NVIDIA started this exercise two years back. Today, there are 70-plus NVIDIA-certified cafes and eight more are coming up soon in cities such as Kolkata and Ahmedabad. A significant portion of the cost of developing a café goes into real estate. Krishna shares, “It costs $4,000 to $5,000 dollars per seat to build a 20-30 seat café.” Apart from the gaming charges, a café also offers food and beverage and merchandise opportunities to the owner. “People usually turn up in groups in these cafes, which also boosts revenue,” says Krishna. Typically, the investments can be recovered within two to three years.

With gaming slowly growing into a familiar pastime for Indians, developers and publishers are hoping for a flashing sign announcing their billion dollars in revenue.