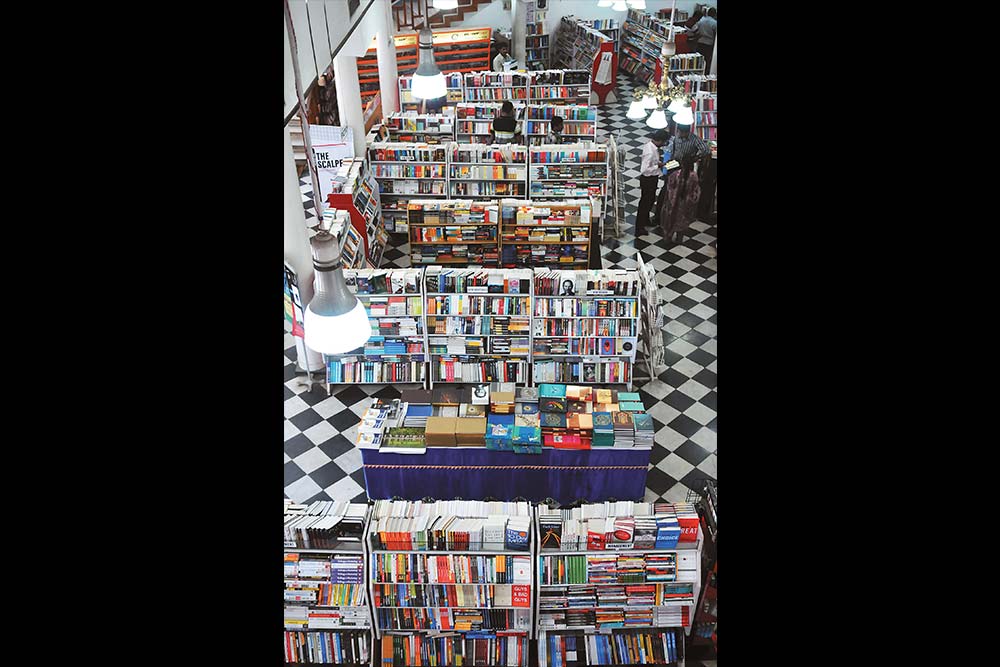

On a dark and squally weekday afternoon, as an incessant rain drums on a very old tiled roof, a stained glass arch welcomes a surprisingly steady flow of customers into a warm and well-lit expanse of shelves lined with books. Inside, the sternly attired yet benign black-and-white visages of father-son founders ‘AJ’ and ‘CH’ Higginbotham continue to gaze upon India’s oldest bookstore, established 1844.

The heritage building not only retains its original chequered marble floor but is still that good ol’ book shop. You know, that place we used to go to buy books before they started selling perfumes and potted plants? “Actually, you could say we sell knowledge in any format—so we do have CDs and DVDs that support our core business of books,” clarifies S Chandrasekhar, wholetime Director, Higginbothams, which operates out of its flagship stores in Chennai and Bangalore, 22 fully-owned branches across small towns like Tirunelveli (a topper in sales), besides university campuses like Manipal.

In 1949, the Chennai-based Amalgamations Group took over Higginbothams in what has since proved to be a benevolent ownership. The iconic chain of bookstores may not be a scintillating case study at a B-school but it has plodded along to remain a haven for, “the books that are published and the people who want to read them,” as Chandrasekhar explains.

“Not changing has become a virtue for Higginbothams,” says Gautam Padmanabhan, CEO of Westland, wholly owned publishing subsidiary of Tata’s Trent. “I think they have the winning formula.”

One Hundred Years Of Solitude

Whereas most prominent retailers have felt compelled to expand into segments like music, toys and entertainment, Higginbothams remains an almost library-like experience. It avoids long tailing, which is the retailing philosophy of selling small quantities of a large number of unique items alongside a much smaller number of popular items in bigger quantities. “Everybody is talking about a long tail these days but if you look for the long tail in bookstores all over the world, you hardly ever find it—nobody wants to hold it, not Borders or Barnes & Noble,” says Hemu Ramaiah, founder and former CEO of the Landmark chain of bookstores. But Higginbotham’s strategy isn’t so about being prescient, as it is about maintaining inertia.

The owners of Higginbothams have taken care to maintain their heritage premises. Another massive restoration effort is in the offing, the efforts of which will be visible in April. Geographically, too, the focus on books serves the company well within its market. Bookstores generally do well in southern India, where real estate costs are lower and the reading habit continues to have a dedicated following.

Academic publishing is the ace Higginbothams holds and takes very seriously. “There was one IIT, one MIT (Madras Institute of Technology) and there were five engineering colleges 20 years ago,” says Chandrasekhar. “Today, we have more than 400 institutions teaching engineering and technology. Naturally, we have to cope with the additional demand.” Textbooks, unlike other categories in publishing, cannot be purchased online. “Buyers are always going to browse and, perhaps, look for a discounted older edition, and then incidentally buy a work of fiction too,” Ramaiah points out. Higginbothams is such a store.

“Modern retailers have to pay modern rents,” says Ramaiah. “The Higginbothams model is surviving because they are working out of old premises with old costs. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be possible [to survive].”

Online sales and digitisation of books have skewed the pitch for brick-and-mortar retailing. “A major problem is competition from websites like Flipkart,” says Padmanabhan. But other than sprucing up their flagship stores with new racks, Higginbothams hasn’t tried to keep up with sectoral trends. Perhaps that’s part of the reason Higginbothams is hardly growing. Last year its topline grew 2.8% to ₹51.25 crore with losses of ₹1.33. But, thanks to “other income” of ₹1.61 crore, it ended the year with marginal profits. The saving grace is that the bookstore has a clean balance sheet with no debt and cash balance of ₹7.5 crore. “Since we are part of a major group, funding has never been a problem,” says Chandrasekhar.

The World is Flat

As with nearly everything else, India is one of the few growing markets for books. Observers note that the US or UK appear to have reached saturation with industry growth rates in the region of 0.5 to 1%. “On the other hand, although we don’t have very scientific methods of keeping track of book sales, we still believe the market is growing at 15-20% y-o-y,” says Padmanabhan.

There are two sides to the Indian books market in which store owners struggle to adapt and remain relevant—the concentration of book retail in metropolitan India is hurting its players but, conversely, there aren’t enough bookshops in tier 2 and 3 cities, leave alone the rural hinterland. “We would like to expand with more small outlets outside railway stations” says Chandrasekhar. “Demand is very good in small towns and the local population does not expect fancy stores that cost a lot to set-up.”

Still standing - Image

At another level, wholesale book-selling is getting squeezed out as foreign publishers such as Random House and Hachette set up base in India, and older players like Penguin and Harper Collins expand their catalogues vigorously. Earlier, distributors imported directly but now stock is purchased from the India offices of foreign imprints. Both developments dried up distribution margins, which sank to 5-7% at the wholesale level. A company like Westland, which was a very active distributor not so long ago, has largely moved to a model where it only distributes what it publishes in-house. Consequently, retail margins on book sales, which used to be about 50%, have now dwindled to between 15-40%.

“Our margins are around 30% on average,” says Chandrasekhar. “When we buy books, we may take low-priced government textbooks for less than 10% discount but we do get some reference books for discounts as high as 40%. We work on a proper product mix to reach operational profitability.”

“Our margins are around 30% on average,” says Chandrasekhar. “When we buy books, we may take low-priced government textbooks for less than 10% discount but we do get some reference books for discounts as high as 40%. We work on a proper product mix to reach operational profitability.”

Fierce competition also forces retailers to ‘push’ stock on a regular basis. Higginbothams, however, has never been known to hold a sale and its inventory management is perforce conservative. “About 85% of the books we are not able to sell cannot be returned to the publishers,” says the soft spoken M Hemalatha, Senior Customer Relations Manager, Higginbothams. “We have to bear the loss. So, we have to manage inventory very carefully.” At the same time, she tries to avoid ‘missed sales’, that is, clients asking for something the store doesn’t have.

“It’s always been a grand place to shop for books,” says historian S Muthiah, who has written of Higginbothams’ illustrious past in his very definitive Madras Rediscovered. “They are one of the earliest ‘English bookshops’ to stock Tamil books.”

“For generations, we have had the identity of a dependable bookseller,” says Chandrasekhar. “It’s an identity we cannot afford to lose on any account.” In that, Higginbothams competes only with itself. After all, no other Indian bookstore can claim to have been around for 167 years.