Jaydeep Barman is as frank as the day, when it comes to narrating his entrepreneurial journey. The co-founder and CEO of Rebel Foods candidly admits that their flagship restaurant brand – Faasos (Fanatic Activism Against Substandard Occidental Shit) got its name as a result of a drunken conversation; and doesn’t shy away from calling himself and the company’s co-founder, Kallol Banerjee, “lazy Bengalis.” In a similar matter-of-fact tone, he recounts how an epiphany changed the fortunes of their company forever.

Barman and Banerjee planted the seed for the venture in Pune and gradually expanded to Mumbai, each set up with an investment of Rs.1 million. American venture capital firm Sequoia’s $5 million funding in 2011 helped Faasos expand its operations further. By 2013, the duo had opened up about 50 small format restaurants in the two cities. These restaurants primarily served a variety of Kolkata’s famous rolls, and 80% of their business came through in-house delivery orders. While it reportedly clocked revenues to the tune of Rs.270 million, high rental costs (20% of total revenue) led to losses worth Rs.150 million.

Barman recalls, “In 2014, we asked a simple question to our customers, ‘Have you seen our outlet?’ Surprisingly, a whopping 74% said they hadn’t.” That served as a ‘eureka’ moment. They realised they could do away with visible façade and shut down high-street stores. Thus, Faasos set up its first ‘cloud kitchen,’ also known as ‘internet restaurant’ in Marol – a suburb in Mumbai. This enabled the company to tap into the catchment area in the neighbourhood without the high rental cost. Since then, sales grew 4x and profits have seen a sharp northward trend.

“We could afford larger kitchens at a fraction of the initial rent,” says Barman. Downsizing 300-500 sq ft outlets into 100 sq ft kitchens dropped rental costs to 2% of total costs. The company closed FY19 at a run rate of Rs.4.5 billion, and is confident of hitting Rs.7 billion in FY20.

Reports estimate Rebel Foods’ net sales increased by 67% to Rs.1.4 billion in FY18. It continues to attract investments, raising a total of $119.6 million till date, according to Crunchbase. This includes the latest Rs.1.1 billion raised in March this year from existing investors including Sequoia, Evolvence India and Lightbox Ventures. Currently valued at $220 million, Faasos operates 200 cloud kitchens across 15 cities, with strongest footholds in Bengaluru, NCR and Mumbai.

Rebel Foods now has nine restaurant brands across various price points and food categories, including Behrouz Biryani, Oven Story, Firangi Bake. These are present through 1,500 cloud kitchens (see: Brand bazooka). It is now among the largest internet restaurant companies in the world, serving over 30,000 orders a day.

Investors are pleased with Rebel Foods’ growth trajectory and are seeing value in their proposition. GV Ravishankar, MD of Sequoia Capital India Advisors, says that Barman’s clarity of thought, coupled with the uniqueness of the business model prompted them to invest in the company. Prashant Mehta, partner of Lightbox Ventures, adds, “In India, you find too many ‘me too’ brands, and frankly, we aren’t interested in them. Going beyond status quo and creating a new model is important for us, and that’s what Rebel Foods has done.” While there were similar cloud kitchens then, such as HolaChef and FreshMenu in 2014, Rebel Foods stood out for the investors because of the founders’ robust expansion plan and focus on scalability through ‘deskilling’.

But the stakes are higher now. Banerjee states that their target is to ensure their restaurant brands become national leaders in their respective categories. “We have been growing at over 100% for the past few years and we see that trend continuing. We are also looking to become a significant global player. Rebel Foods is now expanding to UAE and South East Asia, markets which are similar to India structurally,” he adds. They are unfazed by expected rising costs owing to sufficient funding and local partnerships.

Ravishankar expresses confidence in the company, and says, “They ensured they had full visibility into kitchen operations, quicker turnaround time and built much of this in-house.” Meanwhile, Mehta adds, “Faasos is among the only ones to have expanded at such a fast pace, primarily due to the founders’ clarity of vision.”

Tracing The Roots

But what was it that drew the IIM Lucknow classmates to the food and beverage sector of India? The answer is simple – their love for the famous Kathi rolls of Kolkata. The duo was working with an e-learning company called Brainvisa Technologies in Pune in the early 2000s. “We had both grown up in Kolkata, where rolls were the default option for means on the move. We really missed that in Pune,” recalls Barman. “And it occurred to us as the perfect proposition — an India QSR that serves Kathi rolls,” he adds. It was originally called Faaso’s, but the apostrophe was dropped in 2015, following a rebranding exercise.

In 2004, with about Rs.200,000 investment, they set up Faasos — a small ‘hole in the wall’ store of 200 sq ft, which served wraps and rolls in Pune. They ran it along with their job, by hiring an independent manager. They soon put the business on autopilot with two people managing it. Barman moved to France to pursue his second MBA from INSEAD in 2006, followed by Banerjee in 2007. Barman later worked with McKinsey as an Associate Partner in the UK for about four years. While, Banerjee moved to Singapore to work with Bosch as APAC sales head.

Eventually, in 2010, Barman took a sabbatical and moved back to India. He explains, “After we started Faasos, between 2004 and 2010, at least 20 other wrap companies came in. It felt like we had started a trend. The scalability of the business was impressive because the operation was not very complex. That’s when it became a ‘real’ business for us.” Thus, Rebel Foods was formally incorporated in 2011, and Banerjee joined Barman in 2012. Within three years of opening, the business was overhauled and made a leaner ‘cloud’.

Demystifying The Cloud

A cloud kitchen is essentially a restaurant that has no dine-in facility, only online orders. These ‘kitchens’ are focused more on the ‘catchment’ of customers than on the location of outlets, since it is not a customer-facing service. They require no high-cost ambience, making it a much more cost-efficient business model.

At Rebel Foods, every kitchen addresses a 10-minute drive-time area, set up with a one-time investment of about Rs.4 million, with 10-12 employees, including chefs and a ‘chief delight officer’ — who is responsible for the business operations of that kitchen. The kitchens break even within nine months, says Barman, while a traditional restaurant would take two to three years.

The business model is simple: creating online restaurants, and delivering it through in-house logistics as well as partners such as Swiggy, Zomato and Paytm with revenue share of 15%.

Drawing a comparison with brick-and-mortar restaurants, Barman says that 65% restaurants close down within year one due to ‘wrong’ locations that lead to high rent and less footfall. However, Rebel has never had to shut shop in any of its locations, after using sophisticated algorithms to study customer behaviour and analyse demand.

This data-driven approach, says Barman, has brought wastage down to less than 2% of total costs from 5%. It also enabled the company to have a flexible menu, which can be tailor-made for the location, and during festivals.

Mehta points to another unique feature, which is the way they have ‘deskilled’ the process of cooking any cuisine, ensuring consistency in taste and quality across kitchens. He adds, “If you go to our kitchen, you will see custom equipment for every cuisine. We have a team called ‘Transformer,’ whose role is to look at our process and ‘deskill’ it without losing quality and consistency.” A ‘Transformer’ team comprises chefs, an industrial designer, a nutritionist and a team of engineers (two for robotics and one for automation).

Branching Out

The next pivot for the start-up was when it diversified into a multi-cuisine brand. “In 2016, Faasos had an average order value of Rs.200. But we wanted to take it to Rs.300,” says Barman. To achieve this, the company introduced pizza on its menu, which is pricier than a wrap. Surprisingly, it found no takers, as, “People never believed Faasos could make a good pizza,” says Barman.

It then dawned upon the team that all restaurant brands in the world are known for one product – Starbucks for coffee, Dominos for pizza or McDonalds for burger. “So, we launched the same pizza under a new brand, Oven Story,” he says. Their observation was proven right when, within 24 months, the business grew 6x and they hit an average order value of Rs.320, moving up to Rs.350 recently.

Since then, the brand has diversified into nine food categories where they found ‘need gaps’. They steered clear of value categories with high competition, such as burger, where the food is synonymous with the brand. Barman states that food is the only category where people straddle both value and luxury. “Our objective is to be present for all the needs and price points,” he says.

Every brand they launch follows four stages – experiment, product-market fit, scale-up and marketing. Barman describes the fundamentals of their biryani brand, Behrouz, “The insight was that, in India, every 100 miles, the taste of biryani changes. We wanted a biryani that appeals to all palates. So, we put almonds on it and stayed away from the usual Hyderabadi or Lucknowi biryani flavours. It became a Rs.1.5 billion brand within 18 months,” Despite a slightly more premium pricing than their flagship brand Faasos, Barman believes it is reasonably priced.

Digital Ambience

For a cloud kitchen company, getting the marketing right is as important as getting the product right. A look at Rebel Foods’ journey makes it clear that marketing has always been their strength. Right since their ‘Aaj khane me kya hai’ campaign in 2015, the company has cleverly tied together the themes of ‘food, hunger and variety’ in a witty manner. While it was easy to spot the purple-yellow signage of Faasos on the street when the brand had physical stores, the current brands have virtually no offline presence. The present ones rely only on social media and word of mouth. For instance, the Instagram page of Behrouz has an exotic Persian look and feel to every post, while Sweet Truth, their dessert brand, has an eclectic mix of posts in pastel hues.

The company is also focused on creating the right packaging for each brand. While a traditional restaurant has to ensure good ambience, for cloud kitchen companies, packaging is akin to the ambience, believes Barman. Every brand has a packaging suited to its personality, which costs 3-4% of sales.

Their consistent efforts in this direction have won them a huge follower base on social media. “Rebel Foods has crafted the architecture, segmentation and strategy for every brand very well,” says veteran adman KV Sridhar. He adds that there are two things essential to build a brand: one is the reach, and the second is brand differentiation. Rebel Foods, he believes, delivers on both.

Heat In The clouds

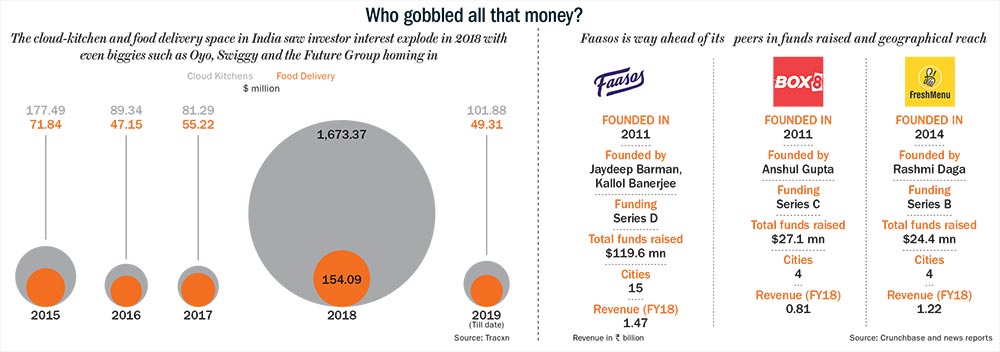

Over the past few years, cloud kitchen space has witnessed a rise in activity (see: Who gobbled all that money?). Rebel’s key competitors include HolaChef (acquired by Ola-owned Foodpanda in 2018), Box8 and FreshMenu. Further, players with bigger pockets, such as Swiggy, which raised $1 billion earlier this year, have also revealed plans to enter this space.

Cloud kitchen as a concept has also evinced interest from unlikely quarters – namely, budget hotel start-up Oyo, and Kishore Biyani-led Future Group. Oyo has reportedly introduced 20 cloud kitchens in Gurugram and Bengaluru and listed them on Swiggy, Zomato and UberEats; while, Future Group is expected to invest about Rs.10 billion in this business.

A stark differentiation that emerges is, while Rebel Foods has raised a lot more funds than its peers, revenue has not scaled commensurately. An analyst who closely tracks consumer internet companies attributes this to the fact that Rebel Foods has gone through a significant strategy shift. Whereas, peers like FreshMenu have always been online kitchens. So, the physical infrastructure burn they had is much lesser. Also, the other two key elements of its strategy, namely — to build a bouquet of brands and to aggressively expand across geographies have proved expensive. FreshMenu, on the contrary, has opted for a more measured scale-up, focusing on the four cities it is present in, and advertising only its main brand.

Scaling aggressively, of course, comes only with higher spends. But which model can be scaled profitably and sustainably will only be tested in the next few years. Going by the offline experience, the additional spend on marketing may only be justified by the premium it can charge to customers. “Even in the offline world, a specialty restaurant is viewed as one that offers better quality than a multi-cuisine restaurant. It is the same logic that applies in the online world. People view them as specialist brands and trust the quality more than an umbrella brand offering different cuisine,” says the analyst.

The competition is heating up, but Mehta believes that Rebel Foods has no reason to worry. “Now, everyone is talking about cloud kitchens. But it is difficult to build a national brand with their own rented kitchens and restaurant brands, which is what Rebel Foods has been able to do,” he says. Ravishankar concurs: “They worked tremendously hard on their tech platform. That is the moat in the business.”

Even as Rebel Foods consolidates its position in India, its international expansion into markets such as Dubai and Indonesia is being worked out. The company has entered into a 50:50 partnership with an unnamed Indonesian firm, and will formally make the announcement in the coming weeks. Rebel will be introducing its brands, Behrouz, Mandarin Oak and Oven Story to the new market. Although too early to estimate, the company expects nearly 50% of its revenues to come from overseas markets in the next 10 years. They are also planning to create an Indonesian and a Japanese cuisine brand, which will be launched in India as well. Mehta believes, they have opportunities in south-east Asia and the middle east, “The model is working in India because of the massively supply constrained market. We are seeing similar situations in other developing markets,” he reasons. “Rebel’s USP starts with the DNA of the team, which is very difficult to replicate, he adds.”

Barman also has ambitious plans for the domestic market, which include having 500 kitchens, launching a health-focused brand and getting local delicacies to other markets, such as sweets of Kolkata, galouti kebab of Lucknow and kachori from Jaipur in non-native regions.

Clearly, an early headstart, innovation and bold decisions have ensured that Rebel Foods stays ahead of competitors. They remain well funded, and are in early talks for another fundraising round. But as newer and bigger players enter the fray, the battle in the clouds is likely to intensify. And it would be interesting to see which cloud will catch silver in the sunshine.