Is it just my belief or has interest in carpets waned of late? Households that would spend inordinately long times selecting their carpets, whether from the “Kashmiri carpetwallah” — and you had to have one to ensure your carpets were washed, shampooed or repaired to keep them in shape — or from showrooms where the best of Mirzapur and Bhadohi compared with those from Srinagar or Jaipur, are now turning their backs on them for the benefit of homes that belong to Architectural Digest rather than the real world. We haven’t done away with carpets yet, but they seem to have turned designer in block shades, just another accoutrement to be changed every few seasons. The bootis and jaalis, the ‘tree of life’ and the ‘paradise garden’ seem to have been — hopefully, temporarily — shelved. What happened? Did we just get bored?

Carpet-weavers confirm that the demand for unconventional but mass-manufactured carpets is on the rise. Modern homes that feature Fendi consoles and Eames lounge chairs are reluctant to pair these with traditional silk carpets, but they’re more accepting if those carpets happen to be antique. Till a few decades ago, expats in our cities could not understand why Indians preferred newer carpets when dealers would offer them older, used ones for a song. It is only now that age and history in a carpet is turning into the stuff of heirlooms, and though the first-ever auction of carpets by Saffronart in mid-March did not set the Ganga on fire, it has set a precedent for those for whom “provenance” might work like a charm.

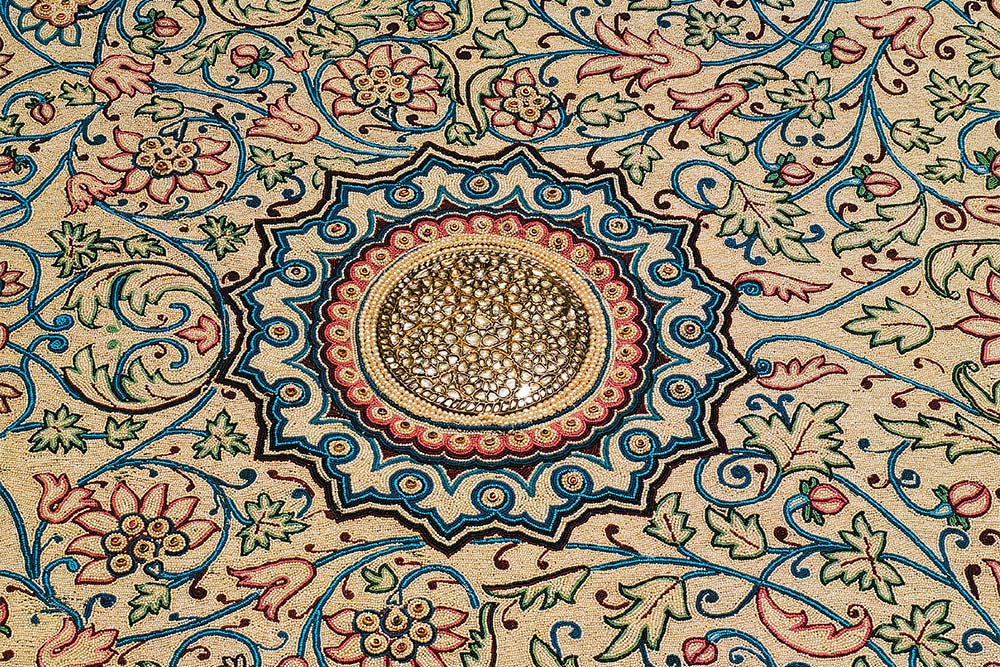

This is particularly interesting because the world record for the highest price paid for a carpet is held for an Indian one that was woven — though “set” might be the more appropriate term, since its design was picked out in gold-set diamonds, sapphires, rubies and emeralds amidst millions of Basra seed pearls — in 1865 for the maharaja of Baroda. Exhibited in England in 1902-03, and again at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1985, it had been carried off to Monaco by the capricious Maharani Sita Devi, and was auctioned by Sotheby’s in Doha in 2009 for a whopping ₹27 crore.

That’s certainly more than most carpets would command — the most expensive at Saffronart turned out to be ₹21 lakh for a Persian carpet, slightly below its estimate of ₹22-25 lakh. And yet, there seems no shortage of either history or provenance given that many of the carpets would have been written up by the munims of their time in their khatas at a time when carpets were commissioned rather than bought off the shelf.

With major carpet-weaving centres emerging across north India under the Mughals, it was again Mughal, and later British, support that resulted in the emergence of the jail carpets. Inmates were hardly concerned about the market, and commissions for extremely large carpets could be taken by the wardens under the supervision of Persian master-weavers. To an extent, that institution continues in Agra, Gwalior, Jaipur and Bikaner — the last town is where I go home for holidays, but it would be impossible to procure a jail carpet locally given the demand.

Sub-continental carpets continue to be expensive on account of the number of knots and colours used in their manufacture. In international auctions, Indian carpets are in a league with the Afghan, Armenian, Chinese, Iranian and Turkish ones. In the West, Spain and France have somewhat of a tradition — but the Aubusson and Savonnerie carpets are no match for Isfahan rugs, Afghani kilims, or Agra carpets.

Part of the reason for the decline in the traditional industry, according to Dhruv Chandra, who “curated” the Saffronart auction and whose Carpet Cellar in New Delhi is a premium destination for carpet-lovers, is because Indians who prefer to buy from carpetwallahs are no longer sure of the quality or, indeed, even the genuineness of material, method or design. “But there are more serious collectors than ever before,” he says — and who knows, in time, perhaps the carpet will become the new object of desire, the way art has become a talking point since the last decade.

The author is a Delhi-based writer and curator