On April 17, Jet Airways announced that it was suspending all its operations since lenders rejected its plea for an interim funding of Rs.9.83 billion. For the airline that was battling a severe cash crunch, it was the final nail in its coffin. “I hate to say it, but has his own karma caught up with him?” says Jitender Bhargava, former executive director of state-owned Air-India, at the turn of events at the country’s most coveted full-service carrier (FSC) brand Jet Airways.

The karmic connection that Bhargava speaks about is in reference to the 69-year-old founder who has had an inglorious exit from a business that had just last year completed its silver jubilee after having taken wings on May 5, 1993.

A typical rags-to-riches story, Naresh Goyal was the poster-boy of Indian aviation having started off his airline with a four-aircraft fleet, painted in a distinct blue and ochre livery and an oblong, serrated sun denoting speed. Over the next couple of decades, Jet not just dominated the skies, but also ensured that it could influence aviation policy and check-mate competition. “A laid-back attitude, influencing government decisions…crony capitalism. All those factors have brought about his (Naresh Goyal’s) downfall,” opines Bhargava.

Despite all its past glory, Jet now joins a long list of casualties that didn’t survive the turbulence in the Indian aviation industry (see: Skyfall). Kingfisher Airlines was the last full service airline to go belly up in 2012, unable to pay interest and salaries. The Reserve Bank of India had prevented banks from converting the debt into the equity and, in the absence of foreign direct investment, the nine-year-old FSC folded with total outstanding of over Rs.80 billion. SpiceJet was also on the brink of collapse and would have joined the list in 2014 if its former promoter, Ajay Singh, hadn’t stepped in and taken over the airlines from Kalanithi Maran, who held 66% of the company back then.

Even as lenders are in a race to find an investor for Jet, GoAir is facing its own set of challenges, grounding more than 10 of its 49 planes due to engine issues and no network to fly them, according to news reports. The airline, which has seen the exit of three CEOs in four years, has also been witnessing an exodus of more than a dozen of its top executives in the past few months.

This distress is puzzling in the fastest growing market in the world, clocking over 52 consecutive months of double-digit growth in passenger traffic until December 2018. The Indian aviation industry is indeed one of the toughest markets to make money in. Battling high fuel prices and a protracted price war, the past couple of years haven’t been an easy ride for Indian carriers.

Low Altitude

Since Jet arrived on the scene, the face of the industry has changed a few times over. In the airlines’ early days, the industry did not have any business model of low-cost carrier or a concept of low fares. Barring Jet Airways, four airlines, East West, ModiLuft, Damania and NEPC, ceased operations during 1995-97. The only two prominent airlines then were Air India and Indian Airlines.

In 2003, it was GR Gopinath who changed the way the Indians flew with the advent of Air Deccan; it has since been referred to as the democratisation of Indian aviation. Two years later, liquor baron Vijay Mallya entered the business as an FSC by positioning itself as a luxury airline and living up to the tag of ‘the king of good times’.

It seemed like a party, but the boat had begun to rock. The FSCs were feeling the heat of Air Deccan with Jet taking over Air Sahara, Air India merging Indian Airlines and eventually Air Deccan flying into Kingfisher Airlines’ arms. The first phase of consolidation, however, ensured that Kingfisher-Deccan and Jet-Sahara together cornered close to 70% of the market share.

Then the massive wave hit. Three new low-cost carriers (LCCs) — SpiceJet, GoAir and IndiGo — stormed the market between 2005 and 2006, and low-cost fares become the name of the game. The FSCs with their high-cost structure were soon caught in the fare war. “Jet had hired a lot of top management people from Indian Airlines and Air India. These folks just copy-pasted the template that they had always followed at the government airlines,” points out Shakti Lumba, an aviation expert, who was also part of the founding team of IndiGo. FSCs, such as Jet and Kingfisher, with their legacies couldn’t match the stripped-down operational style of LCCs.

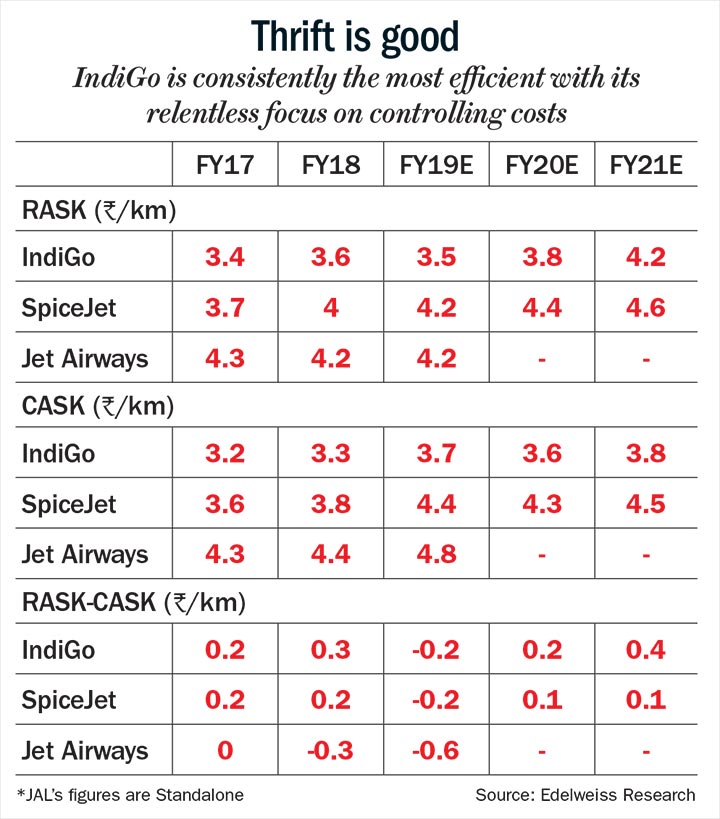

“I have always maintained that cost control is a philosophy and not a strategy which the LCCs understood well but not FSCs,” adds Lumba. For example, while Jet and the Kingfisher were hiring pilots at exorbitant rates, the LCCs were hiring pilots at 20-30% lower cost. “IndiGo’s management didn’t have secretaries and personal assistants. There was just one copier for the entire office. No direct telephone lines and the office space for even the CEO was just confined to 8x8 cubicles,” says Lumba.

Concurring with the views of Lumba, a report by Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (Capa) states that the Indian aviation market is characterised by a situation in which FSCs, which have a cost structure that is around 50% higher than LCCs, have chosen to compete by matching fares rather than reducing costs. And their load factors (which measured utilisation of the transport) remain below those of LCCs. Although the impact of lower loads in business class and on regional aircraft may account for some of this, the differential is significant, states Capa.

Nearly two-third of the seats on domestic routes in India is with LCCs — one of the highest proportions in the world. In fact, when FSCs were ruling the roost, passenger air traffic grew from 21 million in 1995 to 30 million by 2005, but it went four-fold from 30 million to 127 million by 2018 even as several FSCs went under.

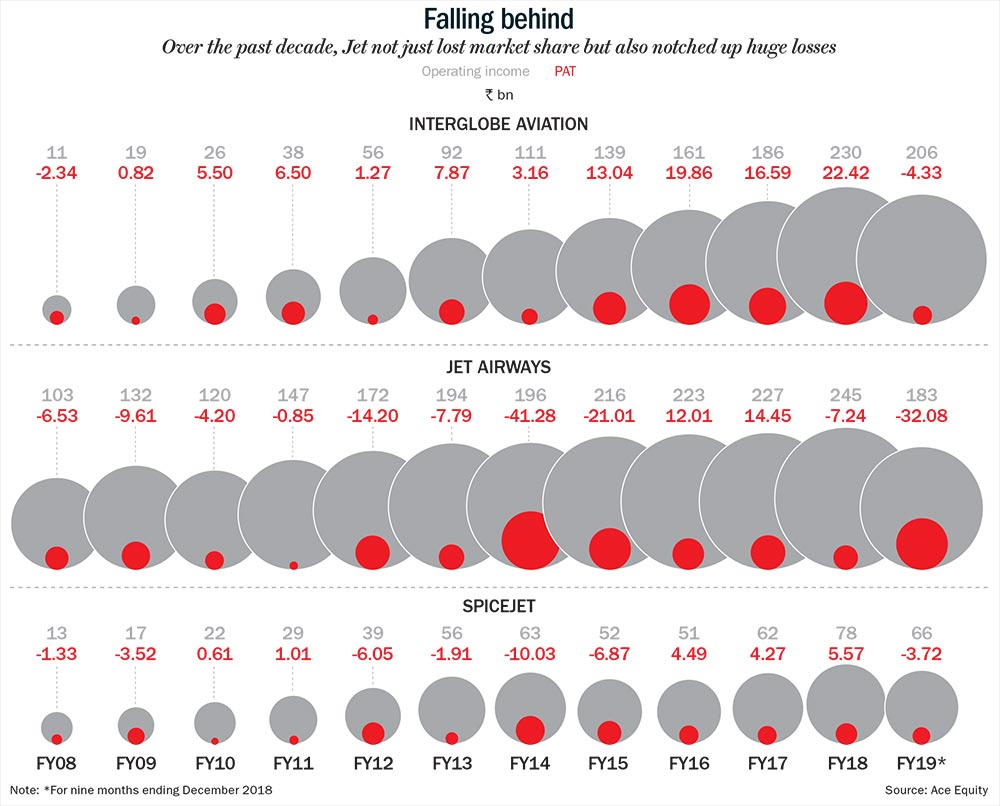

In the decade post the financial crisis of 2008, while LCCs bled, the pain was more acutely felt by FSCs. The boom-bust cycle in crude prices and the operational inefficiencies saw Jet cumulatively posting a loss of Rs.113 billion over FY08-FY18, staying profitable in just two years of FY16 and FY17, when it posted a profit of Rs.12 billion and Rs.14 billion, respectively. A few industry observers trace the beginning of the airlines’ descent back to its acquisition of Air Sahara in 2007 and its decision to buy 20 wide-body aircrafts for its international routes. Jet’s debt burden increased from Rs.60.56 billion in FY07 to Rs.169.09 billion in FY08. In a bid to reduce debt on its books and stay afloat, Jet sold 24% of the company to Etihad Airways for $600 million, including a 50.1% stake in JetPrivilege for $150 million, valuing the frequent-flyer programme at $300 million in April 2013. While the company managed to reduce its burden to Rs.106 billion in 2014, worsening operational performance meant mounting losses and not enough money to service the debt which currently stands at Rs.85 billion (see: Falling behind).

Over the same decade, SpiceJet lost Rs.30 billion and but managed profit of Rs.16 billion in five years. But IndiGo stood out — clocking a cumulative profit of Rs.97 billion, barring just a year of loss of Rs.2 billion in FY08.

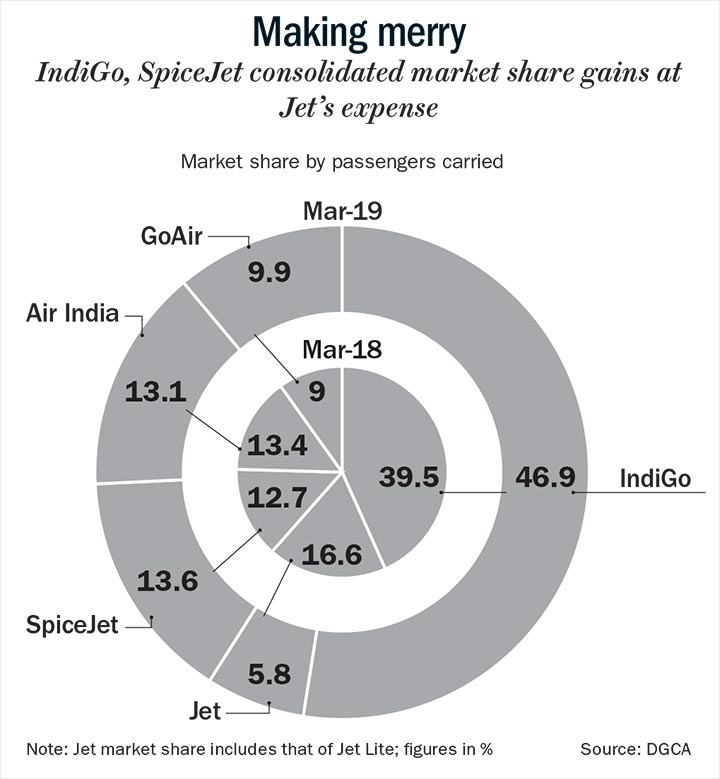

The exit of Kingfisher, which had a market share of 19% in 2011, gave more room for LCCs to grow as it resulted in more slots going their way especially in Mumbai. The biggest beneficiary was IndiGo. By the end of 2012, the low-cost airlines increased its market share from 19.10% to 27.20%. SpiceJet and GoAir also gained, with their market share increasing from 13.60% to 18.50% and 5.50% to 7.60%, respectively. But for Jet who was already reeling under a significant debt burden, it was a missed opportunity. Its market share fell from 26.90% to 23.80% during the same period.

While Jet was using whatever little cash it generated to service its debt, IndiGo went on an aggressive capacity-addition mode. The airline’s low-cost sale-and-leaseback model helped its expansion a great deal. In a sale-and-leaseback model, the airline buys an aircraft, sells it back to a lessor and then leases the plane. This way, you are not saddled with a huge debt burden and it also helps you conserve cash during turbulent times. In fact post 2012, IndiGo stepped up its capacity addition to grab the space left vacant by the departure of Kingfisher. According to a Kotak Institutional Equities report, IndiGo’s market share increased from 29% in FY13 to 38% in FY15.

IndiGo also controlled costs by running only one model, the Airbus 320. In 2005, when IndiGo placed an order for 100 Airbus A320-200 aircrafts in 2005, Rakesh Gangwal swung huge cost savings for the airlines by getting Airbus to lower the price of the aircraft from a little over $60 million to a substantially lower $30 million. Large orders also meant substantial savings since they managed to get free maintenance. Having a standard fleet meant they used 15% less fuel and that worked out really well for IndiGo, since fuel alone accounts for 35% of the operating cost. It was only in 2017 that the company placed its first order for 50 ATRs to deploy on regional routes. So it’s no surprise that it has one of the lowest cost-structures in the country with CASK (cost per available seat kilometre, an industry standard to measure the unit cost in the airlines business) of 3.3 compare with SpiceJet’s 3.8 and Jet’s 4.4 (see: Thrift is good). The airlines is least impacted by turbulence caused by rising oil prices or a depreciating currency.

In FY19, as the rupee tumbled by more than 10% and crude prices flared up to $85 per barrel in October 2018, the entire aviation sector was in the red and Jet slipped into a crisis. In the nine months of FY19, while IndiGo and SpiceJet clocked losses of Rs.4.33 billion and Rs.3.72 billion, Jet posted a loss of Rs.32 billion. In addition to the Rs.72.6 billion due to the banks, the company owes foreign lenders and funds about Rs.30 billion and Rs.10 billion in overdue interest payments taking its gross debt to Rs.112.6 billion.

Also saddled with a large debt of Rs. 575 billion, the state-owned Air India posted a loss of Rs.53 billion in FY18, taking its accumulated losses to Rs.536 billion and continuing its loss-making streak since 2007, when Indian Airlines was merged with the entity. Even as the government took over debt of Rs.290 billion (interest cost of Rs.27 billion) in 2018, Air India still finds itself unable to service debt repayments of Rs.90 billion this year. Though the government in March invited bids from potential buyers for 76% of its stake in Air India, not a single bidder evinced interest in the white elephant. It continues to stay afloat as it is getting bankrolled by public money.

“The aviation industry is a cyclical business with each cycle lasting about seven or eight years. The successful airlines ensure they lose less during the bad times and make enough during the good times to cover up for the losses in the down-cycle,” says KG Vishwanath, director and co-founder, Trinity Aviation Consultants.

Hitting An Air Pocket

With wheat being separated from the chaff, double-digit passenger growth and high-load factors, Indian aviation sector appears to be in a good phase. But things are rarely what they seem. Domestic airlines have been adding capacity at a faster clipand airline seats being a perishable commodity, unsold ones are being sold at throwaway prices. While this means more people have taken to the skies, the growth isn’t ‘real’. “Capacity has grown faster than the organic growth of 12-15%. The Indian aviation market has traditionally grown at 2x of the country’s GDP growth rate. So much of the growth we have seen in the past couple of years has been fuelled by lower fares and that kind of growth is not sustainable,” says Vishwanath.

Before the fares started to trend up post the Jet crisis, a one-way ticket between Mumbai and Delhi in 2018, booked two weeks in advance would cost around Rs.3,300. In fact, the average fares were lower than what they were in 2014 and even in 2012, two instances when the industry hiked fares when SpiceJet was close to the brink of collapse and Kingfisher folded up. In comparison, the fare on the Rajdhani Express on this route is Rs.2,900 for 2AC and close to Rs.4,800 for 1AC. Passengers flying on FSCs such as Air India and Jet Airways pay close to LCC fares in economy class. Lower fares meant that the airlines weren’t covering their costs on most flights. Yields for the aviation industry have remained stubbornly low for the past couple of years.

What’s more, much of this air-traffic growth vanishes when prices start to trend up. For instance, as fares have been increasing following the collapse of Jet Airways, this growth slowed down to 9% in January and 6% in February — the weakest growth rate over the past 60 months. The passenger traffic growth virtually came to a halt, growing a meagre 0.14% in March 2018. “India remains a price sensitive market. So the industry has to decide whether it wants to carry more passengers at lower fares or fewer passengers at a minimum base price that covers all its costs. The Indian carriers have given up on the concept of viability and are focusing on fighting for market share. Investors too seem to more focused on the market share numbers rather than financial performance,” says Harsh Vardhan, chairman, Starair Consulting and the former managing director of Vayudoot.

Apart from tanking fares, all industry players agree that infra and fuel costs are overwhelming. Sunil Bhaskaran, CEO and managing director of AirAsia India, believes that fuel costs and currency will always be an issue. “Fuel cost is expensive in India compared with other global markets, at a time when Indian carriers have given the lowest fares in the world at $40-45 for a 1,000 km flight.” Jet fuel costs make up about 35% of the overall cost for Indian carriers, compared to 25% for international carriers. The differential is because India charges the highest tax on aviation fuel.

Singh, the chairman and managing director of SpiceJet too believes that the government has to rein in fuel cost. “Today we are paying, on average, 40% tax on ATF (aviation turbine fuel), while foreign carriers are paying next to nothing as they get input credit. If we are given a level-playing field in terms of crude prices, Indian carriers will be far more efficient. Once we get the tax environment right, you will find that many more airlines in India will be incentivised to fly directly overseas.”

Though the civil aviation ministry has suggested bringing ATF under the GST ambit, the council of ministers are dithering over taking a decision since it’s a strong revenue source. While excise duty of 11% in levied on ATF, states charge different rates of value-added tax on the fuel.

Spreading Their Wings

While the fires are still being put out in Jet, its peers have wasted no time in grabbing its share in the sky. SpiceJet has signed a codeshare agreement with Emirates, which would open up new routes for its passengers across Europe, the US, Africa and the Middle East. It also has plans of sub-leasing about 22 aircrafts from the lessors of Jet and is already re-branding the aircraft with their insignia. Jet had a 127-aircraft fleet, out of which 16 were owned by the company.

Both IndiGo and SpiceJet are driving capacity growth for the industry, accounting for over 100% of incremental capacity. Consequently, both the airlines have recorded significant gains in market share — 740 bps gain for IndiGo to 46.9% and close to 100 bps gain in SpiceJet’s share to 13.6% (see: Making merry).

There are over 400 slots that have been left vacant in Mumbai and Delhi by Jet and these are being allocated to airlines that bring in extra planes. So there is a sudden scramble to bump up existing capacity. Against an initial plan of 80 planes, domestic airlines are now looking to add nearly 150 in FY20.

While IndiGo is sticking to its annual plan of adding one aircraft a week, SpiceJet will add nearly double the number of aircrafts earlier taking the total to 50. “The sudden reduction of aviation capacity has created a challenging environment in the sector. SpiceJet is committed to working closely with the government authorities to augment capacity and minimise passenger inconvenience,” says Singh. Vistara, AirAsia and GoAir will add the balance 50 aircrafts between the three of them.

In the domestic market alone, the LCC share of total seats is almost 70%. While the share of LCC seats offered on India’s international routes is much smaller, at just under 25%, this share has risen from essentially zero in 2004. And now with Jet Airways’ exit, IndiGo and SpiceJet are moving fast. Of the available seat kilometres or ASKs (a measure of capacity) of Indian carriers on scheduled international routes, Jet accounted for a third (33.5%) as of 2018. IndiGo, which has already doubled its market share on international route to 7.9% as of Q3FY19, is ramping up connection in the lucrative Middle East, once Jet’s stronghold.

Close to 15% of IndiGo’s capacity caters to international operations. “A majority of our international capacity is Gulf-based. Roughly about 12% of our total capacity is deployed on the Middle East routes,” William Boulter, chief commercial officer, IndiGo, was quoted as saying in a media report. The airline, in April, announced that Jeddah and Dammam will be it 17th and 18th international destinations, effective June and July. “Jeddah being the commercial capital and the gateway for Haj, Dammam being the growth centre in Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi being a major cultural and commercial centre in the UAE are critical markets for strengthening our presence in the Middle-East,” says Boulter. With the delivery of the longer range Airbus A321s, which adds another hour of flying, IndiGo sees economic viability in deploying them overseas.

Jal Irani, analyst at Edelweiss, sees merit in the move, “We believe IndiGo’s strategy of replacing the A320neo with A321s in order to pursue the international market is a game-changer since IndiGo may be reluctant to expand its domestic market share beyond 50% due to antitrust issues.”

New Variable

With a blurring of the traditional distinction between FSCs and LCCs, all eyes will be on how Vistara, which began operations in 2015 as a joint venture between Tata Sons and Singapore Airlines (SIA), plots its growth path. As a new entrant, Capa believes, Tata-SIA can engineer a lower cost base than Air India and Jet Airways without the challenges of transformation that a legacy carrier has to face. However, in an extremely price-sensitive market, Tata-SIA will need to carefully consider its market proposition on domestic routes, adds the aviation research firm.

Analysts feel that with the backing of Singapore Airlines, Vistara can pip Air India, though it is a part of Star Alliance, to dominate the connection market.

As existing LCCs IndiGo and GoAir are moving up the value chain, Capa feels there is an opportunity opening up for ultra-low-cost carriers, such as AirAsia India, which launched its services in 2014. In mid-April, the airline announced its network expansion plan by starting 10 new connections from Mumbai to Kochi, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Indore, New Delhi and Bengaluru. The airline, which has a fleet of 20 aircraft covering 19 destinations, had started its operations in Mumbai in January 2019 with its first connection to Bengaluru.

Bhaskaran says, “We plan to add seven to eight aircrafts to make the best of the opportunity from any vacuum that will be created.”

The Long Shadow

Much of the near-term fortune of the industry will rest on what happens to Jet next. With flights being sub-leased or taken back and slots being reallotted, some of the prospective investors are said to be re-thinking their decision to bid for the beleaguered airline. The lenders have selected TPG Capital, Indigo Partners and National Investment and Infrastructure Fund as qualified bidders for Jet and the due diligence process is on with May 10 as the cut-off date for investors to submit their bids.

Of the Rs.85 billion owed by Jet, the State Bank of India (SBI) has the maximum exposure to the airline with a 27% share (Rs.19.58 billion) followed by Punjab National Bank with 24.1 % (Rs.17.46 billion).

Earlier in March, the lenders led by SBI managed to ease out Goyal and family from the board and, in a first, converted the debt of Jet into equity – a leeway that was however denied to Mallya. As per the resolution plan, banks were issued 114 million equity shares for Rs.1 thus giving them majority stake at 50.5%. Additionally, they were to infuse Rs.15 billion in the form of secured debt and initiate the process of finding a new investor by May 2019. But the infusion never did come, despite Jet’s plea for urgency, and finally the airline shut down its operations. The lenders, who are already facing an 80% haircut on their loans, have also decided not to go ahead with the proposed debt to equity and continue to be in control of the 31% of shares pledged by Goyal.

Industry experts say that the new investor will need to pump in about $1.5-2 billion to revive the airline and it has to be done in quick time. “After the Kingfisher crisis, lessors have been demanding six months of deposits and, starting afresh for Jet means it has to put more cash upfront,” points out Lumba. As per reports, Jet owes over Rs.35 billion to its lessors and vendors, and Rs.35 billion to passengers for cancelled tickets. At the time of suspending its services, Jet was operating just six 70-seater ATR turboprops and a single Boeing 737 plane.

The buyers are now unsure about what they will end up getting when they buy Jet. “With no aircraft or slots, the value of Jet Airways has been drastically eroded. The lenders could have drawn up a payment schedule with the lessors for the dues. That at least the airline would be in operation and would have fetched them a better valuation,” says Mark Martin, founder of the Dubai-based aviation consulting firm Martin Consulting.

Regulatory authorities insist that the slots are being given only on a temporary basis for three months and will be returned to Jet once it starts flying again. But with no aircraft in play and employees jumping ship, it remains to be seen how these slots will come back to Jet. “If they are unable to find an investor in four to six weeks, you might as well be writing the obituary for Jet,” says Vardhan. “Once you start losing market share and goodwill, it will take a long time to revive the business. SpiceJet did it overnight and they have managed to come a long way since then.”

While there are lessons to be learnt from the Jet crisis, Vardhan says the industry is far from consolidation. “In the US post the deregulation in the 80s, we saw the entry and exits of many airlines over the next thirty years. There were many failures so we are not the exception. It is only in the past five to six years that there has been no fleet expansion, and post all the consolidation, the US airline industry is doing a lot better. So the Indian market will also take its time to mature.” According to him, airlines with strong cash flow are likely to win in the long term. It is the survival of the fittest. Indeed, the day Goyal stepped down Singh went on to state “today is indeed a sad day for Indian aviation” but the truth is that in a dog-eat-dog business, Goyal should know better that there are no friends, only survivors.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week