Marketing impact is now measured by how well it drives initial footfalls, not sustained hype

Sequencing and restraint are replacing promotional overload as audience fatigue deepens

Advance bookings and audience response increasingly dictate spend decisions, even for big-ticket films

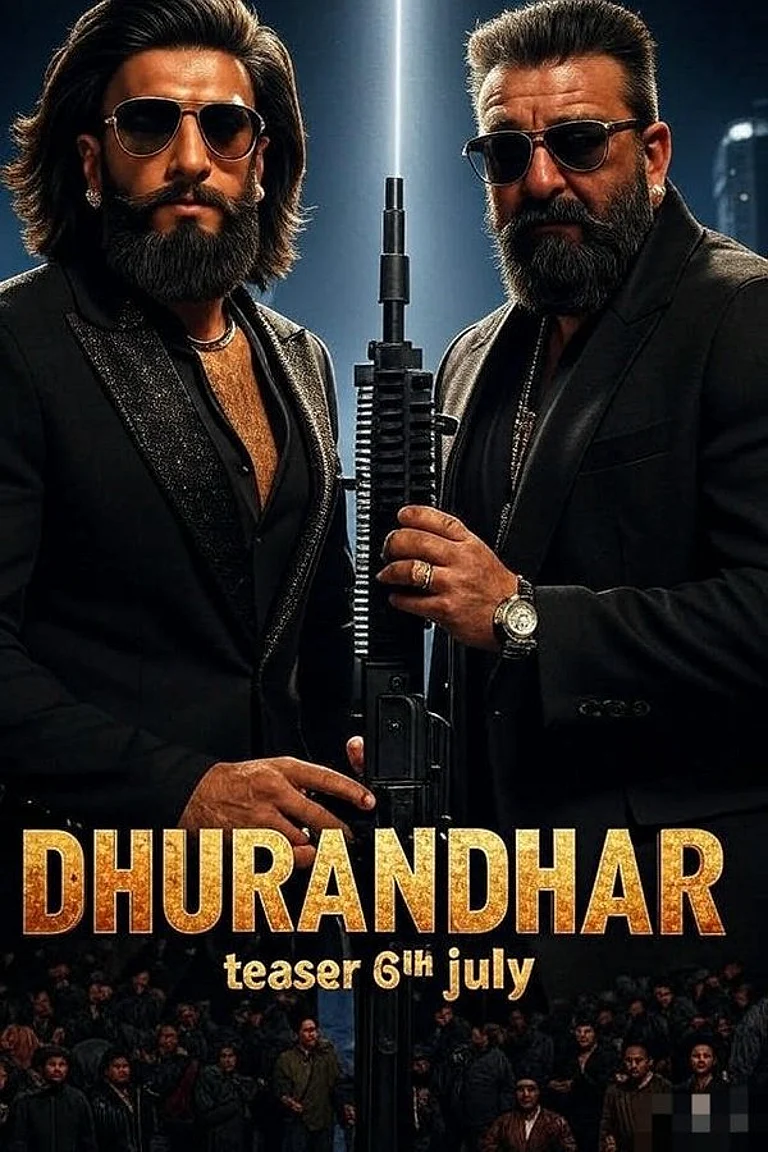

Why 'Dhurandhar' Didn’t Shout Much Before Release? Marketer Varun Gupta on Bollywood Film Marketing

Bollywood’s biggest blockbusters are being marketed with increasing restraint, as studios shift focus from volume-driven promotion to data-led precision. Varun Gupta, who has shaped campaigns for multiple ₹1,000-crore films, argues that marketing’s real commercial role ends with the opening weekend

“Marketing does not decide a film’s fate after Day 3. It only decides the opening, and openings are where the box office business is won or lost. Beyond Day 3, no aggressive marketing spend can save a film that audiences reject”.

Varun Gupta, the marketing director behind four ₹1,000-crore films like RRR, Animal, Kalki and Dhurandhar, is blunt about the limitations of marketing impact in filmmaking. He says the film marketing is not about persuasion, but precision. Until the first teaser or song is released, Gupta says, every film team operates inside a “bubble”, in which nobody believes that they have made a bad movie.

The bubble bursts only when real audience feedback arrives after the film’s first look. And that feedback, he says, clarifies whether the studio should double down on marketing or pull back. In short, studios calibrate marketing spends almost entirely around the opening-weekend data.

When Dhurandhar crossed the ₹1,000-crore mark and went on to set a record-breaking 7.6 million views on OTT debut in the opening weekend, the Bollywood blockbuster marked the payoff of a marketing approach which resisted saturation, rather chose selective visibility, and late-stage reveals to bring curiosity among viewers.

“For Dhurandhar, we were very clear that overexposure would work against the film. The idea was not to keep reminding audiences, but to create curiosity and protect the experience,” Gupta told Outlook Business.

The Ranveer Singh starrer surpassed the benchmarks set by Ranbir Kapoor’s Animal, Hrithik Roshan’s Fighter, Allu Arjun’s Pushpa 2: The Rule. So far, the film grossed ₹1,004 crore in India and $33 million overseas. Of this, according to media reports, the producer’s share stands at around ₹360 crore from the Indian box office and $15 million from overseas collection.

Quiet Marketing Strategy

Behind all four ₹1,000-crore films, Gupta reveals that nowadays, the marketing economics demand navigation and the deep involvement with the directors. “The one common factor was that I was completely involved with the film directors. From deciding which asset should come out at what time and how each one of them should lead to the next, we decided everything together”.

“What has really changed is how assets talk to each other,” Gupta explains. In his view, trailers, songs, teasers and posters are no longer standalone promotional tools but interconnected signals, each designed to prepare audiences for the next reveal. “One asset has to earn the right for the next one to exist,” he says.

This sequencing-first approach has gained prominence as audience fatigue with promotional overload has deepened. With social feeds saturated and theatrical windows shrinking, marketing missteps now carry disproportionate financial consequences. A wrong timed or mispositioned asset can flatten anticipation rather than build it.

Gupta points out that the mistake many campaigns make is assuming more information equals more interest. “Sometimes the strongest strategy is knowing what not to say,” he notes, adding that restraint has become a competitive advantage in itself. The absence of constant updates, interviews or event appearances can signal confidence, especially in high-concept films.

The shift is also visible in how budgets are distributed. Where television once dominated spends, digital now commands the largest share; not just because it is cheaper, but because it allows sharper feedback loops. “You see reactions instantly,” Gupta says. “That changes how quickly you course-correct”.

Crucially, this approach treats marketing as a living system rather than a fixed plan. Each release recalibrates the next, allowing studios to adapt without committing capital prematurely. Gupta’s marketing method prioritises optionality, which keeps strategic doors open until the audience reveals its hand.

The result is a quieter, more controlled form of marketing, one that values coherence over clutter, and decision-making over decibel levels.

Star Power, Spend Paradox

Marketing in filmmaking has become more data-driven and disciplined, however, Gupta points to a persistent contradiction in Bollywood’s business model: the films that need marketing the most often get the least of it. The reason is “star power”.

“There’s an irony in how budgets are allocated. Smaller films or high-concept films actually require more marketing effort, but they rarely have the money. Big stars, who technically need less marketing, end up getting the largest budgets.”

This asymmetry, he argues, distorts return-on-investment calculations across the industry. Star-led films enjoy built-in awareness, loyal fan bases and predictable openings, advantages that reduce marketing risk. Yet studios continue to over-index on spending around marquee names, often as insurance rather than necessity.

Gupta is candid about the enduring power of stardom, particularly in the Hindi market. “There are very few actors for whom people come to celebrate the hero, regardless of the film’s storyline,” he says. “In those cases, quality becomes secondary to emotion”. That emotional equity, however, can also mask inefficiencies in marketing deployment.

The challenge becomes sharper when films attempt to travel across regions. For RRR, Gupta recalls, promotion strategies had to be split sharply by geography. Southern markets required little amplification, while North India demanded intensive outreach to rebuild theatrical confidence post-pandemic. “Audiences weren’t coming back to theatres on their own,” he says. “We had to go to them first.”

In contrast, Kalki avoided traditional publicity altogether, as it used a single visual symbol, the Bujji car mascot, to communicate scale and novelty. “The intent was to signal that this wasn’t a typical star vehicle, but a new cinematic universe,” Gupta explains.

Together, these campaigns highlight a deeper recalibration underway. Marketing decisions are no longer driven solely by celebrity pull or legacy formulas, but by where friction exists in audience adoption. Star power still matters, but according to Gupta, it is treated as a variable to be optimised, not a shortcut to be overfunded.

Metrics That Matter

Dhurandhar has reported ₹400-crore-plus profit, which places it among the most lucrative Indian films ever. It outperformed even larger-scale spectacles such as RRR, KGF: Chapter 2 and Pathaan on return rations rather than sheer topline. The key takeaway for studios is not scale, but conversion.

So far, Shah Rukh Khan’s Jawan was the only Bollywood title to outpace the ₹400-crore profit. Other recent blockbusters trail at a distance, Pathan at around ₹330 crore, Animal near ₹250 crore, and films like Gadar 2 and Stree 2 fall further behind due to weaker non-theatrical monetisation.

However, some media reports stated that Dhurandhar also generated significant value from its non-theatrical streams. The film secured about ₹140 crore from digital, satellite and music rights. Together, recoveries from theatrical and non-theatrical sources have climbed close to ₹650 crore.

This validates that marketing success is no longer measured only by visibility metrics like trailer views, hashtag trends or influencer reach, but by how those signals convert into advance bookings, weekend footfalls and post-theatrical monetisation. In that sense, Dhurandhar’s numbers suggest that fewer assets, deployed with sharper intent, can outperform louder but unfocused campaigns.

“Three things matter most: first look or teaser, trailer, and advance bookings. Songs can go viral, but trailers decide ticket purchases. Advance booking creates recall and urgency. These three define the first two days’ box office from a marketing perspective,” says Gupta.

As Hindi cinema grapples with rising production budgets and tighter theatrical windows, the implications are clear. Marketing is no longer a megaphone; it is a control system. The films that win will not be the ones that shout the loudest, but those that read data early, spend late, and let audience response dictate the next move.