In late 2023, the confidence of India’s tech ecosystem was sinking into a bottomless pit.

Ola's Krutrim in Crisis: Bhavish Aggarwal's Speed is Breaking India's Only AI Unicorn

Bhavish Aggarwal’s AI unicorn, Krutrim, is grappling with flagging traction, a flurry of leadership exits, employee lay-offs and waning staff morale

A year had passed since the launch of ChatGPT and billions of dollars were already being pumped into idea-stage artificial intelligence (AI) start-ups in Silicon Valley. Meanwhile, OpenAI founder Sam Altman had visited India a few months earlier and said that the country shouldn’t aspire to make foundation models. Although seething Indian entrepreneurs took jibes at Altman on social media, nobody was willing to put money where their mouth was.

But Bhavish Aggarwal was not going to take it lying down.

Within a couple of months, the Ola founder created a blitzkrieg by announcing Krutrim, a start-up that would play across the AI value chain from chips to chatbots, and propelling it to the unicorn club.

“He [Altman] came to India and said, ‘Tumse na ho payega [You won’t be able to do it]’. One day, we’ll go to the Bay Area and say, ‘Tumse na ho payega’,” he retorted in a podcast subsequently.

For Aggarwal it was about national pride. He wanted to challenge tech giants in their own dens—OpenAI in models, Nvidia in chips and Microsoft in data centres—to build an entirely sovereign AI infrastructure.

And this meant it was time to unleash the fast-and-furious streak in him once again.

From the beginning Aggarwal didn’t have a choice but to make velocity his calling card. Otherwise, there was no way that Ola could compete with Uber, a global giant with an unending trove of capital, in ride-hailing.

Those who have worked closely with Aggarwal say flip-flops are not surprising. Ola Cabs has started and paused food delivery at least three times and Ola Electric shelved its plans to launch a four-wheeler EV after making a lot of noise about it

For example, when Uber launched a bike-taxi feature in 2016, Ola followed with the offering in a span of 24 hours.

Each time Uber used its deep pockets to carve out a significant market share, Aggarwal hit the ground running to raise more cash to fight back.

He didn’t hesitate to shut down a company within a year of acquiring it for $200mn.

That early conditioning stayed on even when he started Ola Electric. When the Tamil Nadu government helped arrange the land for a factory, it was an uneven terrain, but Aggarwal bought it immediately. In eight months, the factory was already rolling out vehicles.

So, it was only natural that he brought the same pace of goal-setting and execution to Krutrim.

But as is the case in elite sport, the same instincts don’t suit all environments even in business. Today Aggarwal’s need for speed is straining his ambitious AI venture.

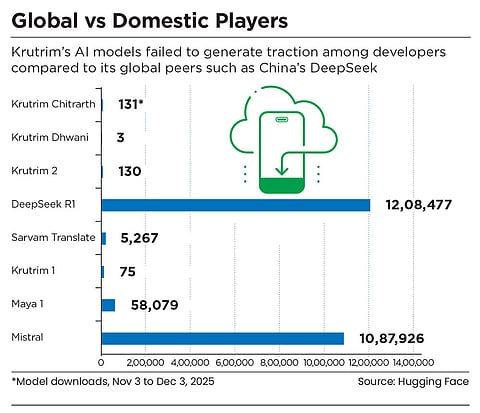

According to Google Play Store data, as of December 13, its AI app which was launched in June has recorded over 100,000 downloads, which is considered a small number in the industry. For comparison, ChatGPT boasted of over 110mn users in India in September, whereas Chinese AI platform DeepSeek had more than 40mn by March end.

When Outlook Business reached out to Ola group, the company refused to comment.

A Moving Target

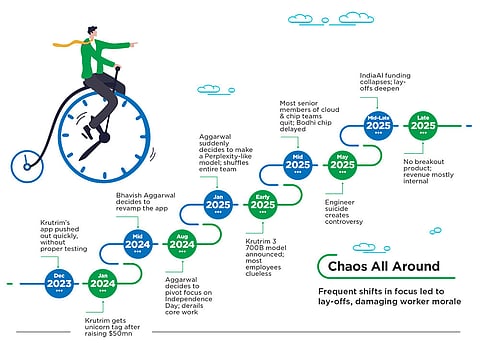

In July last year, Aggarwal set an ambitious goal to transform its AI chatbot, Kruti, into a full-fledged AI assistant. The idea was to make Kruti a broader consumer platform by adding new features in the app such as cab bookings (starting with Ola), food orders, bill payments and shopping tools.

For the next 30 days, the team put in long hours but by the time it was ready it seemed as though the founder’s interest in such a platform had waned, according to sources. It was ultimately launched a year later.

At one point, in early 2025, Aggarwal became fascinated by Silicon Valley-based Perplexity, an AI-powered answer engine, and sought to build something similar. This was the same time when Perplexity decided to expand its presence in India.

Those who have worked closely with Aggarwal say flip-flops are not surprising. This has happened all the way for his other ventures as well. For instance, Ola Cabs has started and paused food delivery at least three times and Ola Electric shelved its plans to launch a four-wheeler electric vehicle (EV) after making a lot of noise about it.

Of course, the word ‘agility’ carries a lot of weight in start-up circles. As young companies in fast-moving markets, start-ups are expected to be quick in their responses—to evolving consumer preferences, fluctuating market conditions and changing competitive landscapes.

However, for Krutrim, it seems to have been too much of a good thing.

“Bhavish can mobilise resources and scale fast. That works well for businesses like Ola Cabs where rapid rollout and operations win. But AI is different. In AI, you face Google and OpenAI from day one. Either you find a niche and keep iterating for years, or you directly compete with the biggest players with sustained product focus,” says a senior Krutrim executive who didn’t want to be named.

Victims of Chaos

Predictably, the abrupt changes in direction have had a disorientating effect on the workforce. It not only meant that employees were frequently going up against unlikely deadlines, but they also had to build up entirely new skillsets.

For instance, teams that were earlier focused on model training—collecting data, validating data quality and building models—were suddenly asked to work on something completely different like Perplexity.

“Building a Perplexity-like product doesn’t need the heavy data-science and research set-up we had,” says another former executive. “It mostly needs engineers who can plug existing open-source models. But we were structured like a model-training organisation, not an application company.”

On another occasion, during the launch of Krutrim Maps, a rival to Google Maps, there was no dedicated sales team, so product managers ended up doing sales conversations as well.

Not surprisingly, the frequent shifts in focus have had a damaging impact on worker morale and led to lay-offs and employee churn. Krutrim’s employee number fell almost a fifth within a few months between May and August last year as over 100 people were let go, according to reports.

“When I joined, within a few days, I became the oldest person in the team as everyone else was fired or had quit,” remembers a former employee.

For this reason, teams at Krutrim often function at half capacity or lower. A group of 30 engineers might have only 15 who are actually active, with the rest looking out for jobs or serving their notice period.

As a result, today, something like accessing an application programming interface (API), a tool that allows different software systems to communicate, that should have taken just 5–10 minutes, is often dragged on for nearly a month.

Very few know where an API is stored, who owns it or whether it is still functional. APIs are often passed around informally through Slack messages or direct requests to individuals who might have left the company weeks ago.

For new engineers, this is a nightmare. One developer recalls spending weeks just trying to locate basic API endpoints and in figuring out which ones were still in use.

The lack of documentation is not the only issue. The company doesn’t have regular team meetings or daily stand-ups, which meant no space to raise questions or clear blockers. Developers spend hours chasing multiple people to confirm which features to prioritise, only to see timelines slip further.

Often, a new team has to rebuild context from scratch and redo work that earlier teams had already completed due to the lack of institutional memory.

“Institutional memory is essential for knowledge retention. As a fast-growing company scales, you need people who can serve as reference points, those who can validate ideas, guide new hires and ensure continuity. These individuals help quickly disseminate critical knowledge to new team members,” says Mahimm Gupta, founder and managing director, PPMS Group, a company that provides human-resource services.

Lieutenants in the Lurch

It’s not unusual in the start-up ecosystem that a company pivots from one product to another while trying to find its feet.

Many a time it’s the staff at the lower levels who bear the brunt of such exercises. However, what’s also true is that a core leadership always remains intact to navigate the storm.

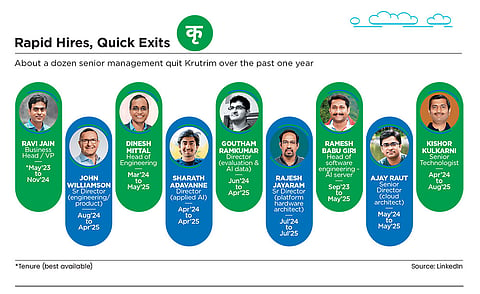

But Aggarwal’s lieutenants—about a dozen—have deserted Krutrim. The pace of leadership exits has reportedly picked up over the past six months.

The long list of senior hires leaving includes the likes of Dinesh Mittal (head of engineering), Sharath Adavanne (director of applied AI), Goutham Ramkumar (director, evaluation and AI data), Rajesh Jayaram (senior director, platform hardware architect), Ramesh Babu Giri (head of software engineering–AI server), Vineet Agarwal (director, corporate finance and investors relations), Ajay Raut (senior director, cloud architect) and Kishor Kulkarni (senior technologist).

One of the issues was that they felt constantly under pressure to deliver quick results, whereas AI being a deep-tech field required patience and consistent experimentation.

“That’s not how AI or software works. No engineering project achieves its best version in the first iteration. You need cycles, refinements, production-hardening,” says a senior executive of Krutim’s cloud computing vertical, requesting annonymity. He left the company because of what he felt were unrealistic deadlines.

“AWS [Amazon Web Services] took about 25 years to reach current standards. But he wanted similar functionality in six months. That was my cue to leave,” he adds.

Industry insiders say Aggarwal has developed a clear pattern of not being able to retain his leadership team over the long term. There have been multiple instances of chief experience officers quitting his companies within months across the Ola group. In that sense, what is playing out at Krutrim isn’t too unusual.

But the one thing that differed this time was that some of the top-deck hires had left their comfortable jobs to join the call of Aggarwal’s national mission. They were not there just for the pay cheques.

One such example was Rajesh Jayaram. After more than two decades at Intel, he had quit his cushy job to join Krutrim. Another was Dinesh Mittal, head of engineering, who had spent 10 years at Intel before signing up with the AI start-up. Yet both left Krutrim after about a year.

Counting the Beans

When these senior executives were being hired, they were promised that there would be enough bandwidth to experiment and money wouldn’t be an issue. They just had to focus on the idea and the work.

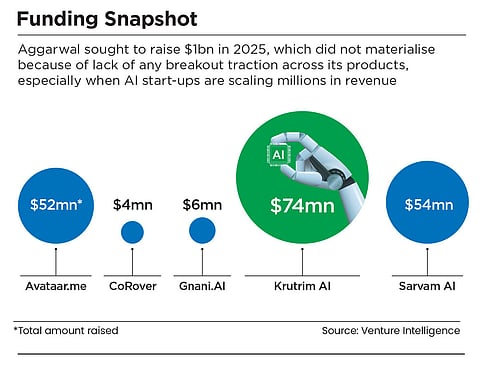

But early last year they felt that cash was becoming an issue. Buying state-of-the-art AI chips, setting up data centres, training large language models and hiring top-notch talent was a costly affair. In the West, the hottest AI start-ups such as Perplexity, Cursor or Windsurf were raising and burning billions of dollars. But Krutrim hasn’t registered any external funding beyond the first round of $50mn in a year.

As the whispers grew louder, Aggarwal took to social media to calm frayed nerves. He announced an investment of ₹2,000 crore (reportedly from his family office) and a commitment to raise ₹10,000 crore (over $1bn) by the end of year, which is yet to materialise.

Meanwhile, Aggarwal has continued to stick his neck out for his vision. Over the past year, he has pledged a chunk of his Ola Electric stake to secure debt for Krutrim.

Industry insiders say that Krutim has been unable to raise more equity money due to a lack of any breakout traction across its products, especially at a time when AI start-ups are scaling from zero to $100mn-plus in revenue within a year.

Aggarwal should perhaps act fast on picking out a niche for Krutrim to attack, and delegating the execution entirely to a core leadership team

At the moment, its bid to develop an AI chip has slipped in its timeline as a large section of the team has quit. The AI models that it has open-sourced has recorded sparse interest (for example, a thousand downloads a month, compared to millions for popular models, according to Hugging Face, an AI platform). And its cloud business doesn’t have any significant external customers, which means a large chunk of its revenue is from Ola’s group companies.

Critics say Krutrim is a case in point of the country’s unreadiness for deep tech. Most of the hottest AI start-ups in Silicon Valley today are headed by founders who have spent the better part of a decade researching AI. That’s far from the reality in India where the focus is to make a quick buck, not solve hard challenges for the long term. “Jaldi se dhanda karo, paisa banao is part of our mindset. Krutrim is no different, every company is told to do that,” says Shayak Mazumdar, founder of AI start-up Adya.

Can Aggarwal still flip the script? Some are still hopeful for the company that is India’s only AI unicorn. “Clearly, the Ola founder is much accomplished but trying to manifest an ambitious AI venture into existence while also trying to turn around a public company [Ola Electric] is a tough balancing act. Both require dedicated focus and time,” says Kashyap Kompella, a tech-industry analyst who tracks the AI sector.

“Bringing in seasoned leaders with authority can provide the bandwidth and wisdom needed for Krutrim to evolve beyond founder-driven desire and intensity into a viable AI company,” adds Kompella.

If there’s one thing that Aggarwal should act fast on, it should perhaps be picking out a niche for Krutrim to attack and delegating the execution entirely to a core leadership team. That might be the best shot that the maverick founder can give himself—and his fellow countrymen—to one day be able to tell counterparts in Silicon Valley, “Tumse na ho payega.”

At the moment, it looks like a pipe dream.