In the 1990s, founder of IT giant Infosys NR Narayana Murthy offered IIT Kanpur shares worth ₹8 crore. Regulations at the time, though, barred equity-based donations. Earlier this year, Murthy said that had the institute accepted and held those shares, they would today be worth nearly ₹2,000 crore, in addition to ₹500 crore in dividends over the past eight years.

Mistrust, Taxes, Red Tape: Inside India’s Broken University Endowment Ecosystem

Universities struggle to grow their endowment funds as a multitude of regulations and bureaucratic roadblocks keep potential donations and gifts from compounding

This was not an isolated case. In the early 2000s, a well-known physicist sought to gift 15 acres of land for a new institute at his alma mater, another premier IIT.

But the transfer required a ₹40 crore stamp duty, which the state government refused to waive. Since the law mandates that stamp duty be paid to the state where the land is located, political wrangling between the state and Centre stalled the process. After eight years, the donation was abandoned.

What Murthy and others were attempting was endowment funding—donations of assets or capital intended to provide universities with long-term financial support.

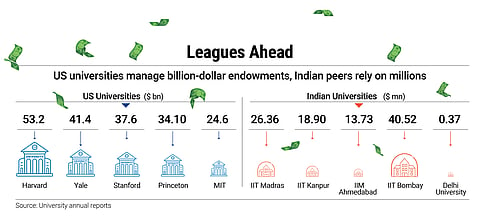

Such funds have existed for centuries in the West. They provide patient, long-duration capital and recycle returns into high-risk R&D. Harvard University, for instance, set up its endowment in the 17th century, making it one of the earliest in the world.

In India, the endowment model is relatively new. It was formally introduced in 2019, when IIT Delhi launched the country’s first structured endowment fund with commitments of ₹250 crore from alumni.

In 2022, the Ministry of Education asked central universities to set up endowment funds, run by boards chaired by vice-chancellors, with rules specifying how much could be spent annually.

“Alumni today are in a position to give back. At the same time, research has become very expensive, with equipment costing millions of dollars, which the government alone cannot fund. Endowments help institutes invest in cutting-edge areas,” says Arjun Malhotra, cofounder of leading IT-services company HCL and member, board of governors of IIT Kharagpur Foundation.

Globally, endowments are a financial backbone supporting scholarships, research and infrastructure. Over the past few decades, endowment funds of Ivy League colleges have accumulated tens of billions of dollars and become the largest backers of private equity-venture capital (PE-VC) funds. In doing so, they have not only earned outsized returns, but helped create a thriving private funding ecosystem for start-ups.

The X-Factors

For starters, India lacks a single comprehensive law governing endowment funds. Instead, institutions must navigate a patchwork of regulations depending on how the fund is structured.

Private trusts fall under the Indian Trusts Act, 1882, while public charitable trusts are governed by state laws. The Income Tax Act, 1961, sets conditions for tax exemptions and donor benefits, while the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010, regulates how foreign donations can be received and used.

“Endowment funds face heavy compliance burdens under fragmented legal regimes. They require multiple registrations under the IT Act, Companies Act, FCRA and state Charity Acts, resulting in frequent filings and audits. Funds are also subject to stringent scrutiny,” says Rahul Charkha, partner at Economic Laws Practice, a law firm.

Cultural perceptions have also slowed the growth of endowment funds in India. For the longest time, endowment initiatives carried the stigma of privatisation

Another hurdle is the strong preference for cash. If a donor contributes shares or land, trusts have to sell the asset within a year and invest the proceeds in “safe” instruments to retain tax exemptions. This restriction is why institutions often nudge alumni toward cash donations.

Then there are concerns over yield. Experts note that when potential contributors are asked for large sums, the first question is: what yields are you generating? At first glance, this may seem strange. After all, the intent is to donate. But donors want visibility on how their contributions are saved and used.

Many feel the yield is too low compared to what their own wealth managers could generate, an industry source says. So instead of contributing to the endowment, they prefer to directly fund philanthropic programmes.

Even when Indian universities do raise endowment-style funds, their investments are tightly constrained by Rule 17C of the Income Tax Rules, which specifies that to retain tax exemptions, charitable institutions can invest only in “safe” avenues such as bank deposits, government securities and a limited set of debt funds. They are not permitted to deploy the funds in category I/II/III alternative investment funds, which includes professionally managed venture-capital funds.

“Since charitable organisations enjoy tax exemptions, such restrictions are in place to ensure that the endowment is not invested in relatively risky avenues,” says Mayank Arora, partner, The Chambers of Bharat Chugh, a law chamber.

Safe and Stagnant

Experts are united in their agreement on the need for change. Treating endowments as if their sole purpose is to sit in ultra-safe, low-return instruments defeats the objective to grow a perpetual corpus whose returns can support long-term institutional goals.

“And it is not that we didn’t ask for a change in Section 17C,” says a source who didn’t wish to be named.

According to them, two reasons explain the lack of progress. First, public officials are reluctant to authorise riskier allocations because the career risks they face outweigh the rewards. Responsibility is fragmented across ministries and regulators, which means that long-term benefits are credited to successors, but any losses are blamed on the decision-maker. This discourages risk-taking.

Second, too many agencies are involved. “We’ve taken cases to Sebi [Securities and Exchange Board of India], RBI, Irda [Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority], Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Education since about 2017. We had meetings with ministers and officials, but the process is slow and often ends in bureaucratic inertia or ambiguous circulars,” says an investor pushing for the amendment of Section 17C.

Questions sent to the Ministry of Finance did not elicit a response.

Underlying all this, sources say, is a deeper institutional bias: a lack of trust in universities’ ability to manage money, coupled with a belief that public funds require the tightest possible oversight.

“Even pension funds today invest in mutual funds and other instruments. For example, the National Pension System has a mandate to put a portion of its corpus in equities and other higher-risk securities,” says Anurag Rastogi, former chief executive, IIT Delhi Endowment Fund.

Culture Wars

It isn’t just regulation that slows the growth of endowment funds in India. Cultural perceptions have also played a role.

For the longest time, endowment initiatives carried the stigma of privatisation. In the 1990s, when the first alumnus of a premier institute attempted to make a major gift, the move was met with suspicion. It reportedly took nearly two years for the donor’s cheque to clear.

Attitudes have softened since then, but resistance persists. In 2023, the announcement of an endowment fund for Delhi University sparked strong reactions from faculty and students. Abha Dev Habib, secretary of the Democratic Teachers’ Front, questioned whether private companies, being for-profit entities, would contribute funds without expecting anything in return.

There is also a structural divide between IITs and IIMs that are backed by strong alumni networks and have built sizeable endowments and central universities that lag behind. IIT Madras, for example, has raised more than ₹350 crore, compared to just ₹10 crore at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

“For central universities, it’s new. Many assume the government fully funds us, so alumni support isn’t necessary. We are trying to change this perception. Endowment is not for day-to-day expenses but for future generations,” says Anil Kumar, chief executive of the University of Delhi Foundation.

The lack of professional fundraising capacity is also a challenge. “Across Indian universities, the total number of advancement professionals—those managing fundraising and alumni relations—is far fewer than what a single mid-sized US state university employs,” says Kapil Kaul, chief executive of the IIT Kanpur Development Foundation.

Bridging the Gap

Not all is bleak. Awareness in India has been steadily growing, with several marquee institutions receiving contributions in recent years.

“We’ve moved from zero awareness to active discussions at the highest levels. Alumni sentiment is strong. It’s about structuring and governance now. I believe India will have multi-billion-dollar endowment funds. IIT Kharagpur alone, with 90,000 alumni, could become the largest in India,” says Vikram Gupta, founder of the VC fund IvyCap Ventures, part of whose profit is designed to go back to seed endowment funds across universities in India. Gupta also helped conceptualised and set up the first endowment fund at IIT Delhi.

While still uncommon, contributions in the form of company stock are also beginning to take hold through institutes’ overseas charitable arms. For instance, IIT Delhi’s Endowment Foundation in the US has facilitated stock donations from alumni, which are particularly attractive under US tax laws as donors are exempt from capital gains tax. IIT Bombay and IIT Madras have also received similar contributions.

If India aspires to be a “product nation” rather than only a services hub, it has to empower its universities accordingly.

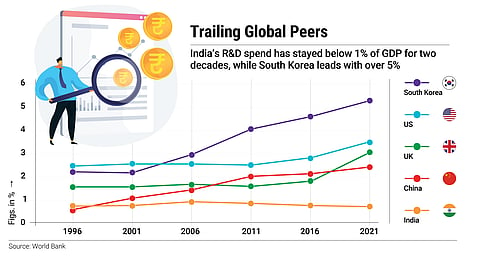

India spends less than 1% of GDP on R&D—a fraction of what countries like South Korea, the US and Japan invest. Endowments could help bridge this gap by providing a steady pool of capital for long-term research, without depending on annual government grants.

“Indian universities remain confined to a narrow corridor of options. This regulatory straitjacket starves campuses of the financial muscle needed to support world-class research and attract top talent. Unlocking endowments for dynamic, broad-based capital deployment is essential if our universities are to compete globally,” says Pranav Pai, managing partner, 3one4 Capital, an early-stage VC fund.

Without strong endowments, India’s best ideas will continue to depend on foreign investors. With them, universities can become the foundation of both economic resilience and technological self-reliance.