When PepsiCo came knocking in the early 1990s, Haldiram said no.

From a Family Snack Business to Global Ambition, Haldiram is Writing its Own Destiny

A decades-old family business turned bhujia into a $10bn brand on its own terms. Now, Temasek is backing its next global leap

In the years following the liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation reforms, global brands began flooding the country. For many local businesses, partnering with a multinational company seemed like the smart thing to do. But for Haldiram, a family-run bhujia maker from Bikaner, the idea of giving up its name was non-negotiable.

PepsiCo’s offer to buy out the company made perfect sense on paper. While Haldiram was already a familiar name, it would have given the business deep-pocketed backing in a newly opened market. But Manoharlal Agarwal, who led the Delhi branch of the business, refused.

“I refused to give up our brand, our dream,” he later recalled in The Bhujia Barons by Pavitra Kumar.

That moment of defiance came to define the company’s path. PepsiCo went on to launch its snack brand Lehar but never came close to Haldiram’s dominance. Decades later, Haldiram has grown into one of India’s largest food companies, big enough to rival multinational fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) giants.

When Singapore’s state-backed investment firm Temasek acquired a 9% stake in Haldiram Snacks Food earlier this year—the merged entity in which the Delhi family holds 56% and the Nagpur family 44%—it underscored that Haldiram was not just a snack-maker. The $1bn transaction, among the largest private-equity deals in India’s consumer sector, was rare. Global investors rarely back an unlisted, family-run food company.

But despite staying away from the stock markets and media spotlight, Haldiram commands a level of trust and scale that few rivals can match, making it a true outlier in the industry.

In 2022–23, India’s organised traditional snacks market was valued at around ₹17,900 crore, according to Frost & Sullivan India, a business-consulting firm. Haldiram held an estimated 40% share of the market.

“The variety and range of their products are so vast that almost every Indian seems to like something from their portfolio. Their continuous innovation, deep understanding of Indian consumers and strong traction even outside India make them a truly unique company,” says Arvind Singhal, chairman and managing director, The Knowledge Company, a management consultancy.

The Delhi Disruption

Before it got to that position, Haldiram was a modest sweet shop founded in Bikaner in 1937 by Ganga Bhishen Agarwal, fondly known as Haldiram. Soon after its establishment, the business branched out to Kolkata and Nagpur, both cities with strong Marwari trading roots. While Ganga Bhishen and his elder son Moolchand stayed in Bikaner, the younger son, Rameshwarlal, was sent to Kolkata and Moolchand’s eldest son, Shiv Kishan, to Nagpur.

Growth was modest for decades. The real turning point came in the 1980s, when the family set up shop in Delhi under the third generation led by Manoharlal, supported by his brother Shiv Kishan.

Manoharlal’s grasp of production, supply and marketing changed the game. Against opposition from his grandfather and father Moolchand, he decided to make ingredients in-house. The older generations saw this as unnecessary expense.

He faced similar pushback when he proposed upgrading from stamped polythene bags to branded, superior packaging material. But Manoharlal persisted.

His efforts paid off. In-house production ensured hygiene, while standardised packaging strengthened the brand’s identity. Manoharlal’s defiance, first in modernising the business and later in expanding to Delhi, became the foundation of Haldiram’s transformation.

The Delhi venture soon outpaced its Kolkata counterpart, surviving setbacks such as the 1984 riots, which destroyed its factory, and intense competition from foreign brands after liberalisation.

Haldiram’s strength lay in its instinct for the Indian consumer. While multinational rivals relied on heavy advertising, Haldiram focused on innovation—from wholesale distribution and zip-pouch packaging to extending product shelf life.

Now, with the fourth generation at the helm, the business is readying for a global expansion that goes beyond the Indian diaspora.

Beyond Nostalgia

That ambition is backed by numbers. In 2013–14, Haldiram’s ₹3,500-crore revenue exceeded the combined India revenues of PepsiCo and McDonald’s, brands that took the US snacking culture overseas.

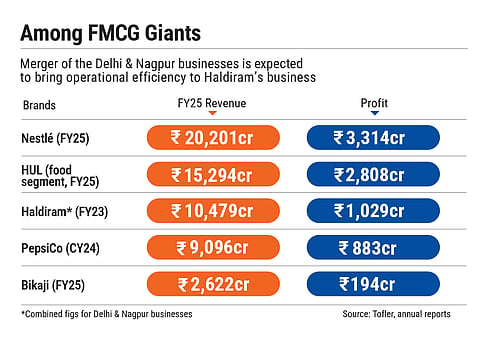

At a valuation of about ₹88,000 crore ($10bn), Haldiram now rubs shoulders with FMCG heavyweights such as Dabur and Tata Consumer Products, which have market capitalisations of about ₹86,000 crore and ₹1.15 lakh crore, respectively. In revenue terms, its performance is comparable to Hindustan Unilever’s foods division, which reported ₹15,294 crore in 2024–25.

Since then, the gap has widened. Between 2020–21 and 2022–23, Haldiram’s revenue from operations grew 46% from ₹7,151 crore to ₹10,479 crore, while profit rose 47% to cross ₹1,000 crore, according to Tofler, a business-intelligence platform.

In comparison, PepsiCo India reported consolidated revenue from operations of ₹9,096.62 crore in 2024, with a profit of ₹883.39 crore.

This growth has made Haldiram one of India’s most formidable food brands and an attractive bet for global investors. If it can turn India’s food rituals into global cravings, it has the potential to build a market well beyond diaspora demand.

Beyond capital, the Temasek deal is expected to bring stronger governance and professional management to the enterprise, helping it expand. Its global network and experience with family-led companies is likely to strengthen supply-chain capabilities and overseas expansion.

As Singhal notes, the investor may be able to “open some doors for Haldiram, which it may not be able to do on its own”, whether through distribution, manufacturing technology or product development capabilities from other companies in its portfolio.

While Temasek will support expansion in Southeast Asia, backing from investment firms Alpha Wave Global and International Holding Company, which together hold about 6% stake in the company, will help extend Haldiram’s footprint in the US and West Asia.

Yet winning global tastebuds may be harder than nostalgia sales suggest. Haldiram’s products are sold in over 100 countries, but a significant share of overseas business comes from just the US and West Asia, driven by Indians seeking a taste of home.

But most countries already have their own comfort foods. With global investors behind it, Haldiram may now have the confidence to experiment more.

“It could have expanded overseas on its own. Having global investors by its side will give confidence to experiment and take risks. It can adapt its products to suit local tastes in other countries,” says Satish Meena, adviser at Datum Intelligence, a market-analytics firm.

The Next Frontier

Exports may have carried Haldiram’s name overseas, but they still account for only about 10% of business. The real battle remains in India, where competition is fierce and consumer preferences are changing.

Brands such as Balaji Wafers and Bikaji Foods are already pushing beyond regional strongholds, investing in capacity and distribution, courting private equity and polishing brand narratives.

Bikaji has built a loyal base in Rajasthan, Bihar and Assam and has set its sights on the heartlands of Haldiram: Delhi, Haryana, Punjab and UP. Haldiram itself is yet to stake its claim in the east.

According to Aditya Jhaver, director at Crisil Ratings, branded snacks will continue to expand as the country’s unorganised food market formalises. This transition opens space not only for Haldiram but for rivals eager to capture share ceded by smaller players. Then there is logistics. Plants closer to consumption hubs reduce costs and improve freshness: advantages Haldiram will need to match.

Consumer expectations are shifting as well. Concerns around obesity and processed food are reshaping snacking habits. Haldiram, industry experts say, remains relatively low-key in promoting its healthier offerings.

Beyond external pressures, internal challenges loom. The larger Haldiram family has a history of internal rifts and legal disputes, which led to the model of clearly defined territories for sons involved in the business.

The Delhi and Nagpur branches have so far operated independently. Experts say the advantage is that because the two businesses don’t operate in the same markets, integration challenges related to vendors or retail networks will be minimal.

“The journey ahead will depend on how the company is run after the merger. The real task now is to integrate systems and processes, and the organisational structure of the combined entity,” says Meena.

A family-owned business transitioning to a co-owned structure goes through multiple changes, says Pankaj Jaju, founder and chief executive, Metta Capital Advisors, a boutique investment bank. “A private-equity investor acts as a partner whose interest is in growth and value creation, so they ask tough questions. Decisions on acquisitions, investments and business plans are scrutinised,” says Jaju.

For a company accustomed to charting its own course, the success of its partnership with Temasek will depend on whether tradition and professionalism can grow side by side.