Curled up inside a blanket on a cold winter night in Delhi, yearning for some warmth, it is easy to forget how bad the Delhi summers were this past year. Through April, May and June of 2024, the average temperature in India’s capital was over 40 degrees Celsius. Air-conditioners ran without rest at offices and homes that could afford them. On May 29, Delhi suffered its worst summer day on record. The temperature soared to 52.9 degrees Celsius. Two days later, power demand peaked at a baffling 250GW, nearly 15GW more than power authorities had projected.

Battery Low: What’s Stopping India’s Green Power Progress

India produces enough green energy to power many of its largest cities yet lacks the storage to use it efficiently. A nation blazing forward must leap ahead in battery technology to stay on course

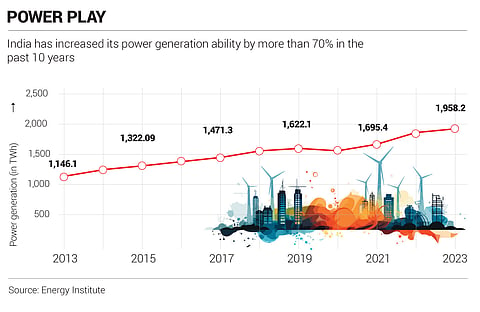

Yet, nothing happened. There were no big outages reported. Yes, the Union power ministry let all thermal power plants run at full capacity. But that was that. And that was a pleasant surprise. Only 12 years ago, in July of 2012, India had suffered the largest blackout in modern history. Roughly 620mn people, around 9% of the world population, were left without power for 13 hours after the northern and eastern power grids collapsed due to overload.

A number of things have changed in India’s power supply infrastructure in these 12 years. One of them is the unification of the power transmission network, which allows the grid operator to shift load from thermal to nuclear, solar, wind and hydro from one corner to the other. The other, and more important step, has been the increase in the ability to produce renewable energy.

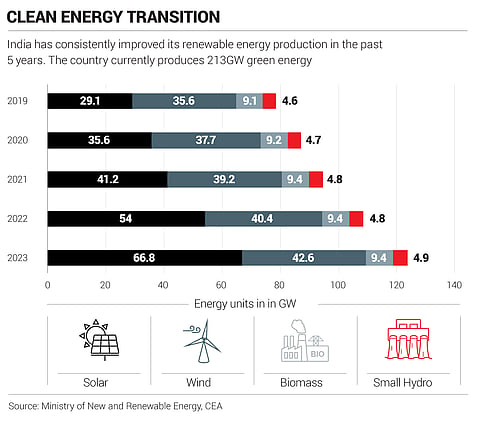

India produces over 213GW renewable energy (up from just over 187GW in 2023) leveraging several natural energy sources as of 2024. This ability takes the country forward in realising its net-zero emissions goal. But to actually realise that goal and meet the ever-increasing power demand of the fifth-largest economy in the world, the country needs to figure out at least one thing more: storing the green energy it produces.

Lithium is a core component of energy storage systems and India does not have enough of it. Consequently, it has to import most of the lithium it uses

In this, India lags its peers. Green energy across the world is primarily stored in battery energy storage systems (BESS). And most of these systems are built using lithium, a chemical element in short supply. India does not have adequate BESS infrastructure. As a result, while it is able to produce 213GW of renewable energy, its battery storage infrastructure can keep only 33MW, according to a report by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII).

The Centre recognises the problem. In 2023, it set up a national framework for energy storage systems in a bid to ramp up India’s energy storage capacity. The framework involved a number of policy and regulatory measures as well as measures for performance-linked incentives. It also approved a viability gap funding of ₹3,760 crore for 40% of BESS projects. But all these measures so far have had limited impact.

Li-ion at Heart

One of the primary reasons why India has failed to adequately scale up its BESS capacity is the lack of lithium. Most BESS capacity around the world is built on lithium ion (Li-ion) batteries. Lithium is a core component of energy storage systems, and India does not have enough of it. Consequently, it has to import most of the lithium it uses—which is both expensive and slow.

The few lithium reserves that exist in the country are still to be tapped. A reserve was discovered in Jammu and Kashmir’s Reasi district in 2023. It was a tremendous discovery because when it was found, authorities called it the seventh-largest resource of lithium globally. It was said that the reserve contains 5.6% of the world’s lithium reserves. But there have been no bids to extract yet.

Smaller reserves have been discovered in Jharkhand and Rajasthan. But according to analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA), minerals like lithium take 16.5 years to go from discovery to production. “Any significant output from these reserves is at least a decade away,” says Vignesh Shankar, managing director at FSG, a consulting firm. He adds that the environmental and social impacts of such lithium extraction need also be considered.

Meanwhile, India’s lithium demand is seeing a sharp rise not only due to the growing focus on renewable energy but also electric vehicles (EVs). India’s lithium demand could rise from 1,634 tonnes in 2022 to 40,499 tonnes by 2030, according to projections by the International Institute of Sustainable Development. Of this, grid storage demand of total lithium demand is expected to go up from zero in 2022 to 19% in 2030.

To supply this demand domestically, the government should push more production-linked incentive schemes, says Shankar. “However, to achieve true self-sufficiency, the focus should be to not only increase domestic production capabilities but also promote recycling initiatives and explore alternative technologies such as sodium-ion and flow batteries to diversify energy storage,” he adds.

Testing Ground

Another factor that has slowed the evolution of battery storage technology in the country is the lack of adequate testing centres. Testing battery storage units is necessary not only for safety and reliability but also for functionality in special locales. VK Saraswat, a member of the government think tank Niti Aayog, calls the lack of nationally accredited testing centres “one of the biggest gaps in India’s energy storage ecosystem”.

Speaking at Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry’s (Ficci) Energy Storage Conference 2024, Saraswat said, “India requires a universal standard for all types of energy storage systems.” He believes the quickest way to ramp up testing infrastructure is by authorising third-party testing and certification.

The Bureau of Indian Standards’ (BIS) electrotechnology in mobility sectional committee (ETD 51) and stationary storage (ETD 52) are looking to adapt existing global standards for India. A lot of progress has been made, but this will take more time, according to Avik Sanyal, General Manager, BESS, Gensol Engineering.

Sanyal says that global committees on standardisation and testing centres such as the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and American Underwriter Laboratories (ULs) have been working on Li-ion batteries for more than 25 years, and India has started late.

“In recent years, there has been a spurt in testing services across the world. They typically follow European Union guidelines and/or American ones. While these are exhaustive standards aimed at testing battery performance and quality not all are suited for Indian conditions [high temperature and humidity]. There is an urgent need to develop Indian standards,” adds Sanyal.

Question of Research

And of course, among the multiple reasons for the lack of battery technology innovation, is the lack of adequate focus on research and development (R&D), a condition that afflicts most Indian industries. At 0.64% of gross domestic product (GDP), India spends less on R&D than most other similar economies, according to data from policy think tank WRI India.

China spends nearly 2.4% of its GDP on R&D efforts, Japan 3.2%, the US 3.4% and South Korea 4.7%. Add to that, most of the R&D funding in India comes from the government, with businesses contributing only 41%. But in the US, China, Japan and South Korea, businesses contribute over 70%.

According to data compiled by WRI India, key research areas in the battery ecosystem are raw-material mining, processing, cell-component manufacturing, battery assembly and recycling. Ministries of the government of India are involved in various aspects of the battery supply chain through R&D, laboratories and public sector undertakings (PSUs).

But the research that happens in India is mostly at the level of basic technology development with little to no focus on commercialisation. On the other hand, businesses like to get involved in research at the level of commercialisation. As a result, much of the technology developed in India faces challenges at the stage of commercialisation.

While these numbers are impressive, the disparity between research investment and deployment puts India at a competitive disadvantage. Despite ranking fourth in the world in terms of renewable energy capacity, India’s R&D expenditure is well below the annual average spent by member states of the IEA which is $118mn or ₹986 crore.

The Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) calculated that total government spending in renewable energy research and development in financial year 2022 was ₹124 crore across all sectors, including national wind, solar and bioenergy institutes and other programmes. Last year, the government more than doubled this number with the National Green Hydrogen Initiative that has a research and development budget of ₹400 crore.

“There is cognisance of this in policymaking circles. Initiatives like Anusandhan National Research Foundation [ANRF] established by the ANRF Act 2023 grow and foster a culture of research and innovation, and are needed to bridge the gap and establish leadership,” says Deepak Krishnan, deputy director-energy at WRI India.

Energy storage will be key to sustainability in the years to come. And India’s realisation of its net-zero emissions target will hinge on how quickly and efficiently it can expand its ability to store renewable energy. Without that, the path to net zero seems broadly improbable.