In 1991, Kurt Cobain, lead singer of the American grunge band Nirvana, wrote a song about a man with bipolar disorder who turned to religion after losing the love of his life. He titled it “Lithium”, after the chemical used to treat the condition at the time.

India's Self-Reliance in Battery Manufacturing Needs A Lithium Recycling Strategy

India lacks domestic lithium reserves, yet its electric-mobility ambitions hinge on it. Recycling is the only viable solution, but the country’s efforts remain inadequate, informal and technologically backward

Three decades on, batteries made of lithium are expected to help save the polar ice caps from melting by leading the electric-mobility transition. Yet India possesses little to no lithium of its own. Its only viable strategy is to recycle. But its efforts are far from enough.

Millions of electric rickshaws ply the streets of India’s towns and cities. Their batteries degrade, malfunction and are swapped. But what becomes of the old ones?

One of two things. Some are returned to manufacturers. Most, however, end up in scrapyards. Nearly 95% of India’s lithium-ion batteries are believed to land in rubbish tips, though no official figures exist.

Spent lithium batteries hold valuable minerals—lithium, cobalt, nickel and more. Informal waste workers pick them apart, extracting select materials, but much of the lithium is lost. India discards an estimated 50,000–70,000 metric tonnes of lithium-ion batteries annually. A single scrap mobile phone or laptop contains 3–4gm of lithium; an electric-vehicle battery holds nearly 8gm.

Why Batteries Need Recycling?

The argument for efficient lithium recycling is compelling. Experts warn that inadequate recycling could cost India more than $1bn in foreign-exchange losses as reliance on costly imports grows.

Recycling lithium is not merely a green imperative—it also makes financial sense. If correctly processed, recycled lithium is as good as newly mined lithium. According to the US Department of Energy, producing one tonne of battery-grade lithium requires 250 tonnes of ore and 750 tonnes of brine. By contrast, the same amount can be extracted from just 28 tonnes of spent lithium-ion batteries.

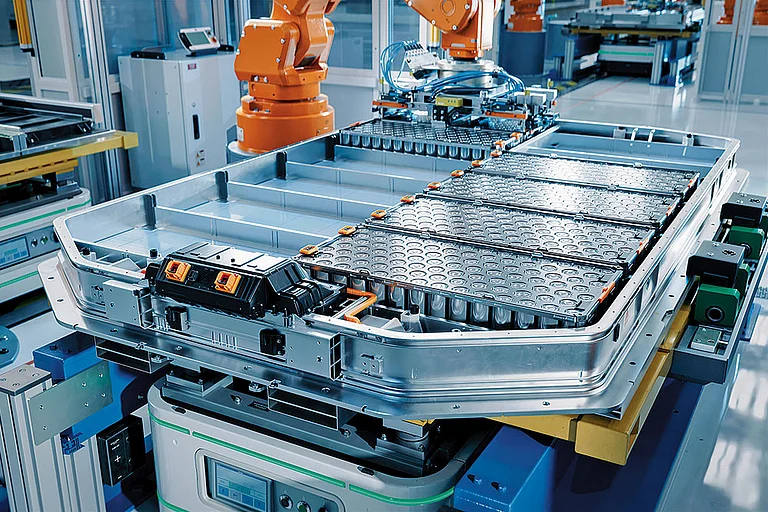

But recycling is a complex process. Once a battery pack is dismantled, the cells undergo mechanical recycling, in which they are shredded in water or nitrogen. This yields black mass—a powdery substance containing valuable metals—along with copper, aluminium and plastic separators.

Black mass can then be processed using pyrometallurgy (high-temperature extraction), hydrometallurgy (water-based metal separation) or direct recycling. Hydrometallurgy is generally considered the most efficient means of recovering lithium.

Despite these advances, India’s recycling efforts rarely extend beyond the creation of black mass. Meanwhile, China dominates the global lithium-recycling market, processing nearly 2.86mn tonnes—more than the US and Europe combined.

What's Holding Back Battery Recycling?

India’s lithium-recycling industry remains largely informal, with no standardised collection or disposal systems for battery waste.

“There is little public awareness about responsible disposal,” says Dr Anjali Singh, Senior Fellow at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. “Batteries from e-waste often end up mixed with other forms of the waste, making segregation challenging,” she adds.

Small- and mid-sized recyclers, meanwhile, lack access to advanced technology, relying instead on crude and dangerous methods. “Informal units often use basic equipment such as heat guns, which produce toxic emissions and create fire hazards,” says ALN Rao, head of circular economy at clean-tech start-up Recykal.

India's Progress in Battery Recycling

Change is afoot, albeit sluggish. In the past four years, several firms have entered the lithium-recycling space. More may come lured by government incentives such as the Union Budget’s proposal to exempt customs duty on lithium-ion battery scrap.

Attero, Lohum and Lico Materials are among the companies making strides in formalising lithium recycling. Attero, for instance, employs a hydrometallurgy-like process. “Our recovery rate is 98% for cobalt, nickel, lithium carbonate and graphite,” says chief executive Nitin Gupta.

According to Rao, state intervention is crucial for scaling up. “The government must support recyclers with capital subsidies, tax rebates, land allotments and access to technology,” he says.

India’s lithium-ion battery-recycling market is projected to grow from $3.79bn in 2021 to $14.89bn by 2030, at an annual growth rate of 21.6%.

For India, transitioning to electric mobility without domestic lithium reserves presents an immense challenge, threatening to inflate import bills. Unless the country stumbles upon significant deposits of its own, efficient recycling is the only way forward.