On January 15, the Supreme Court delivered a ruling with significant implications for India as a predictable destination for foreign investment.

A Bench comprising Justices R. Mahadevan and J.B. Pardiwala ruled on the scope of tax protections under the India–Mauritius DTAA.

The judgment turned on the interpretation of a key treaty provision, reshaping how capital-gains immunity can be applied.

Falling FDI and Retreating Capital: Why SC Ruling on Tiger Global's Flipkart Sale Matters

In the judgment, a bench of Justices R Mahadevan and J.B. Pardiwala essentially nullified the tax immunity given by the India-Mauritius double taxation avoidance agreement by reinterpreting the meaning of a key phrase within the treaty

On January 15, the Supreme Court of India delivered a judgement that can have far-reaching implications for India’s reputation as a dependable destination for foreign investment with stable and predictable laws. In the judgment, a bench of Justices R Mahadevan and J.B. Pardiwala essentially nullified the tax immunity given by the India-Mauritius double taxation avoidance agreement by reinterpreting the meaning of a key phrase within the treaty.

An Early Unicorn

The story goes back to the early days of India’s consumer internet, when two former Amazon engineers, Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal, decided to start an online bookselling website, Flipkart, in Bengaluru in 2007. Over time, much like its US-based inspiration Amazon, Flipkart diversified into the sales of all kinds of commodities, including electronics, mobile phones, appliances, garments and even packaged food items. Soon after, Amazon, the original online bookseller-turned-mega-retailer, also entered India after giving a tough time to brick-and-mortar-based retailers such as Walmart in its home market.

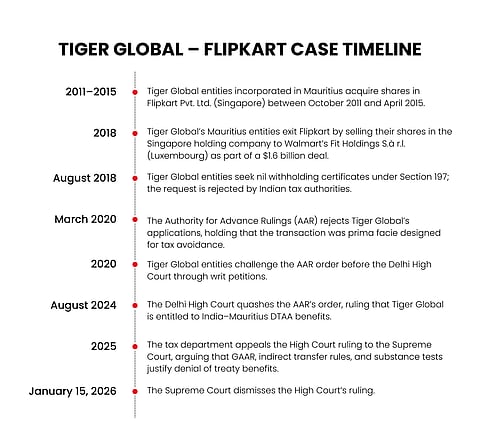

Away from Indian shores, Tiger Global, a US-based private equity firm, was quietly building up a 22% stake in the Indian ecommerce company. As was common at the time, it chose Mauritius as the location of its funds as India had a Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement or DTAA with the island nation. International companies typically routed their Indian investments through entities based in Mauritius to ensure that they would not have to pay tax on their profit when they exited their investments later.

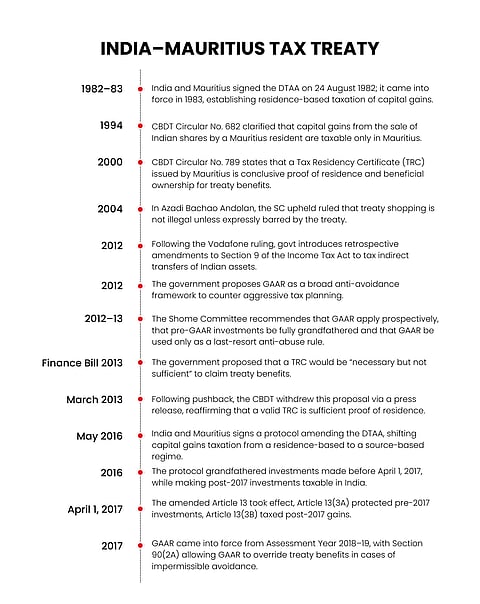

India had put this arrangement in place in 1982 in a bid to attract foreign investments, effectively offering a zero capital tax regime to overseas investors. This worked well for all parties, and succeeded in generating tens of billions of dollars of foreign investment for India every year, fueling everything from tech startups to a stock market boom.

However, in 2016, Indian authorities decided to gradually bring this arrangement to a close, reasoning that the revenue lost was not worth the investments attracted. They decided to redraw the agreement with Mauritius with effect from April 1, 2017.

Under the reworked treaty, a full capital gains tax would be made applicable to investments routed through Mauritius, after a two-year transition period stretching from 2017 to 2019. The new treaty also allowed higher scrutiny of the ownership structures of Mauritian firms through GAAR or General Anti-Avoidance Rule, which would help pinpoint the true identity and location of the owners.

To ensure that these new norms did not apply retrospectively to those who had already invested under the old rules, a clause—10(1)(d)—was utilised to give immunity to investments made before April 1, 2017 from the new provisions.

While all this was happening, US-based Walmart decided it was worth its while to take the fight to Amazon’s territory, albeit in a different country. It settled on Flipkart, halfway around the globe, as its mode of attack.

A deal was soon reached between Walmart and a clutch of investors in Flipkart—including Tiger Global, who together sold an aggregate stake of 77% in the Indian e-retailer to Walmart in a multi-billion dollar deal.

As was the custom, Tiger Global approached the tax authorities for a zero tax certificate pointing out that it was a pre-2017 investment. To its surprise, the fund was served with a denial. It then followed up with the Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR), a quasi-judicial body. However, here too, it received the same reply.

This led the firm to approach the Delhi High Court, which, in 2024, upheld its arguments and directed the department to issue no-tax certificates.

However, that was not the end of the story. The IT Department filed an appeal in the Supreme Court, resulting in the current judgment.

Core Issues

The core issue raised by the Income Tax Department in its appeal against the High Court judgment was that the arrangement under which Tiger Global owned its stake in Flipkart amounted to a tax-avoidant structure under India’s GAAR or General Anti-Avoidance Rule. The GAAR, originally incorporated in 2012, contained provisions to ‘pierce the corporate veil’, go deep into a company’s ownership, and tax a company based on its ‘real’ or ‘beneficial’ or ‘ultimate’ owner, irrespective of its form or structure.

In response, Tiger Global pointed out that, as this was a pre-2017 investment, GAAR did not apply.

It pointed out that the government had repeatedly clarified that GAAR would not apply to investments made before April 1 2017.

Tiger Global also presented a clarification contained in the Indian finance minister’s budget speech of 2015, which read: "GAAR would apply prospectively to investments made on or after 01.04.2017."

Tiger Global also produced a press release issued by the government of India on May 5, 2015, stating: “At the same time, existing investments, i.e. investments made before 1.4.2017 have been grand-fathered and will not be subject to capital gains taxation in India."

The investor also pointed to a clarification made on the website of Central Board of Direct Taxes, dated January 27, 2017, which said: “Grandfathering under Rule 10U(1)(d) [of the Indo-Mauritius treaty] will be available to investments made before 1st April 2017."

SC Stand

However, in a surprising twist, the Supreme Court denied the benefit of immunity from GAAR scrutiny to the Tiger Global-Walmart sale. This was achieved by reinterpreting the meaning of the words ‘without prejudice to’ contained in a key clause within the Indo-Mauritius treaty.

The court nullified the clause that grants immunity from GAAR to pre-2017 investments by interpreting the meaning of the phrase “without prejudice to the provisions of” contained in the subsequent clause.

In the India Mauritius treaty, the source of immunity for investments made before April 1, 2017 is contained in clause 10U(1).

This clause is then followed by another clause which states that no immunity will be granted for the sale of investments after April 1, 2017, but “without prejudice to” the earlier clause creating the exemption for pre-2017 investments.

While traditionally, the phrase “without prejudice to x clause”—when attached to a provision—is understood to mean that the provision will not stand in the way of the operation of clause x, the Supreme Court interpreted it to mean the opposite. It ruled that “Without prejudice to the provisions of clause (d)” meant that the following clause would also apply to the immunity-granting ‘clause (d)’.

In its order, the court said: “By the use of the words “without prejudice to the provisions of clause (d) of sub-rule (1)”,...[GAAR] is made applicable to any arrangement, irrespective of the date on which it was entered into…”

Thus, the court nullified the immunity-granting clause (d) of the treaty, making it inoperative and pointless.

Legal Implications

The judgment, which has negated arguably the most important part of the India-Mauritius agreement, can have both legal, practical and reputational implications for India.

According to experts, the judgment can open the floodgates for the IT Department to deny or even re-examine capital gains tax benefits claimed by investors in recent years, and deny the benefit in the future.

Ankit Jain, Partner in Ved Jain and Associates—a CA firm—pointed out that investors who claimed capital gain tax exemption recently for their exits from pre-2017 investments can now expect potential difficulties going ahead. “All pre-2017 exits that claimed treaty benefits are now at high risk of scrutiny,” Jain said.

This can also impact the current value of pre-2017 investments, as the buyers will now have to worry about the tax-man showing up at their door after they buy such assets from foreign investors who don’t have a presence in India. “Buyers in secondary transactions will demand higher holdbacks or indemnities to cover potential tax liabilities, reducing the liquidity for exits,” Jain said.

Siddharth Pai, founding partner of Bengaluru-based venture capital (VC) firm 3One4, also said investors who are holding positions dating back to 2017 and expecting a tax-free exit, will now have to redo their numbers.

“The Tax Department will closely scrutinise exits to Mauritius-based entities. While many fund managers have pivoted to Singapore, SEBI AIFs or GIFT IFSC, the past presence in Mauritius will require investors and advisors to re-examine their tax risk and make provisions,” Pai said.

He also pointed out that the Income Tax Act permits reopening old tax returns for up to six years—or up to 2019. “But exits after that can face scrutiny based on this judgement if they took advantage of the DTAA. Given the exit volume over the last two years, there is extreme uncertainty today,” the 3One4 co-founder noted.

Broken Trust, Hungry Startups

Beyond the immediate legal impact, the judgment can also have long-term consequences for India’s image as an investment destination with stable, predictable laws.

“If a country gives a jurisdiction a special benefit, investors will operate from there. You cannot tell them ten years later that you no longer understand why the benefit existed and now treat them as criminals by default. That destroys trust,” said an investor.

Others echoed similar concerns: “Once a government makes a policy and investors change their behaviour based on it, the government cannot simply forget why the policy existed and reverse course years later,” said another.

They pointed out that India gave Mauritius domicile-specific tax benefits for a reason. “Over time, instead of clearly explaining changes, the rules were tweaked repeatedly until the framework became a grey area,” said another.

The thinning trust, some of them said, is a key reason inflows of foreign capital have slowed from the country in recent years. Growth-stage funding for startups in India shows a clear slowdown in deal value after peaking earlier in the decade.

India’s foreign direct investment numbers have shown a declining trend after hitting a peak in 2021-2022, when the net flow, after adjusting for outflows, was around $70-72 billion, which has declined to around $52 billion.

“The fundamental problem is the Indian administration itself. It does not understand how investors think and fails to provide long-term policy certainty. Tax rates change, tax treaties change, and past commitments are revisited without explanation,” one earlier mentioned investor told Outlook Business.

Investment trends data from Tracxn show a steep decline in funding in 2023, with investment dropping to $186 million despite a relatively high number of rounds. Funding showed signs of recovery in 2024 at around $253 million across 11 rounds and strengthened further in 2025, reaching $345.5 million, although the number of rounds fell to five, indicating a shift towards fewer but larger deals.

“Growth-stage capital is disappearing. There is very little Series B, C or D funding. Deep tech is still early-stage, and without growth capital, IP will start moving abroad,” said one investor

What’s more, the trend has even affected listed equities, which are traditionally considered low-risk, given that a foreign investor can exit its position and cash out in a matter of minutes in case of adverse regulatory developments.

In calendar year 2025, India saw net foreign portfolio investor (FPI) outflows of $11.8 billion, according to data from SBI Capital Markets (SBICAPS) EcoCapsule in January. However, flows into listed equity are affected by a range of short-term factors, including high market valuations and worries about tariffs.

“In 2025, more money left India than came in. That is catastrophic for a developing economy. India cannot double its GDP without sustained capital inflows,” one of the earlier mentioned persons noted.

As a result, the rupee recorded its sharpest annual fall in three years, sliding about 5% against the US dollar, even though the dollar itself was not particularly strong during the year.

With the Supreme Court now placing the entire framework under scrutiny, it remains unclear which path the Indian government will choose, whether to prioritise revenue collection by backing tax authorities or to reassure investors by offering policy stability in pursuit of long-term economic growth.