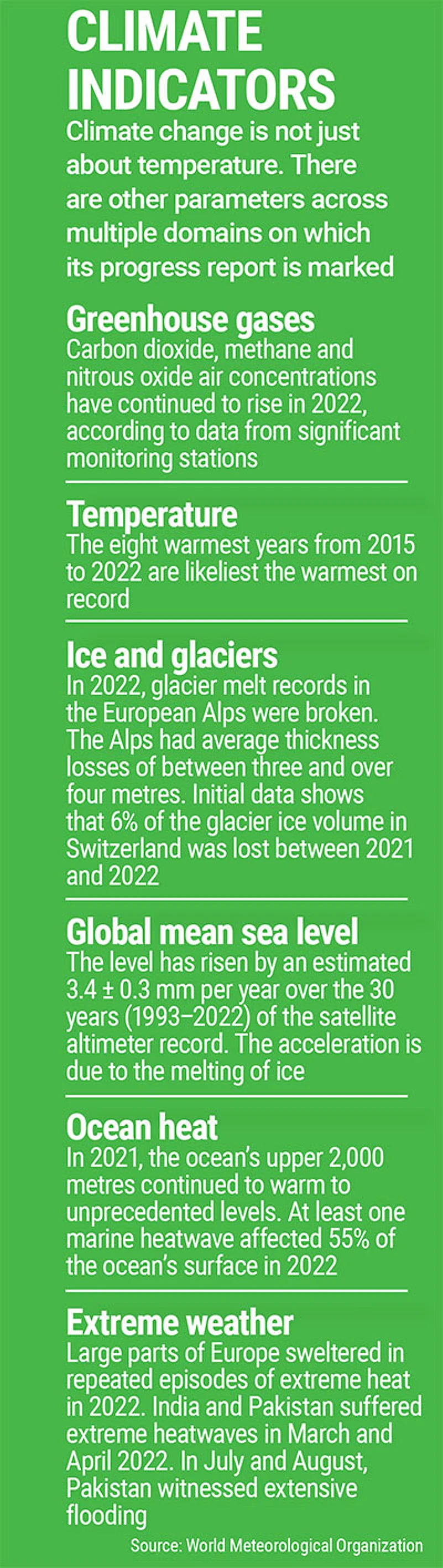

The global climate crisis, from being a non-issue a few decades ago, to turning into a cause for discomfort and now finally becoming a state that is threatening to snowball into a planet-destroying catastrophe, has metamorphosed rapidly. Yet, despite the extent of damage that has already been done, the urgency to address it seems to be missing.

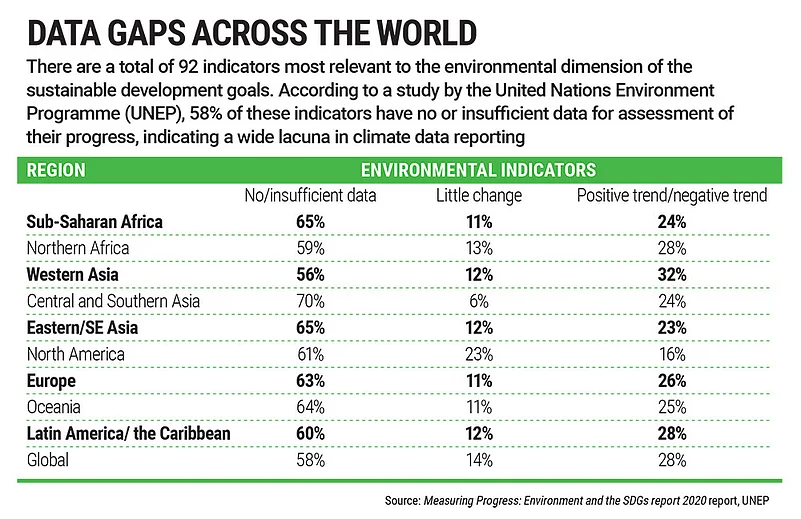

According to the Measuring Progress: Environment and the SDGs report, released by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Convention on Biological Diversity, the world is set to miss its targets for environment-related sustainable development goals of 2030. Much of the blame lies on data, or rather the lack of it, say experts.

“The planet cares more about greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than about availability of data. But what cannot be measured cannot be managed,” says international climate expert Malte Hessenius, an analyst at German sustainable finance think tank Climate & Company. The philosophy, coming from the financial sector which is the key driver of economic decisions including sustainability, indicates that adequate data on the climate impacts and risks of portfolio companies is needed to fully leverage the power of the financial markets.

There are 92 SDG indicators related to the environment, according to the UNEP report. Globally, 58% of these indicators have no or insufficient data to assess any progress in the respective areas, the report states. There is either little change or a negative trend observed in 14% of the indicators, while only 28% have reported a positive trend. In case of India, there is no or insufficient data for 44% of these indicators.

At an event last year, Reserve Bank of India governor Shaktikanta Das said that data gaps had emerged as a key hindrance in effective macroeconomic policymaking, including for climate change, for global central banks.

“The risk assessment methods and models for analysing climate-related risks are, at present, limited by lack of usable data,” he said.

India’s Data Position

At the G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia, in November, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stressed on the need to address data gaps globally. He also announced that the principle of “data for development” would be integrated in the theme of “One Earth, One Family, One Future” by India during its G20 presidency this year.

India has several conventional sources from which it draws information. Data on climate indicators like emissions, weather and oceans, ecosystems and glaciers comes from institutions like the National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, the India Meteorological Department, the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which collect and analyse data on climate. It also uses inputs from the Indian Space Research Organisation’s satellite programme as well as field observations and remote sensing.

Anjal Prakash, research director and adjunct associate professor at the Indian School of Business, says, “Though India has a relatively strong infrastructure for data collection and analysis, there are still gaps in the available data, especially in remote and inaccessible areas and for some specific parameters that are important for understanding the impacts of climate change.”

Data gaps also pose challenges to the long-term health and resilience of various sections of the natural environment. Among all sectors, agriculture calls for special attention. According to the World Bank, 41.49% of the total workforce in India in 2020 was employed in agriculture. However, its contribution to the economy was estimated to be just around 20% in 2020–21, as per the National Statistical Office.

There remain gaps in terms of integrated climate modelling which requires multi-disciplinary approaches and capacity building in terms of supercomputing facilities, according to Shailly Kedia, senior fellow with the sustainable development and outreach division at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), Delhi.

Even where the data is available, the challenges remain. “The problem is taking this information to farmers and other impacted communities in a manner which is actionable by them,” Kedia adds. She stresses on the need for regional-level modelling of climate data to create climate resilient infrastructure services.

Grappling with Gaps

Citing an example of data gaps, Prakash notes that very few glaciers are monitored across the Himalayas, as a result of which there is not enough data on glacier mass balance, which refers to the growth and loss of ice from the glacier system. High costs attributed to the monitoring of glaciers are an impediment, he says.

“We need more data on permafrost. The met stations for monitoring rainfall are also sparse. Climate change is specific and rainfall may change within a five kilometre radius, so we need more monitoring stations,” he elaborates.

Climate change has made weather forecasting challenging despite advancements in technology and availability of high-performing computational facilities. There is lack of precise data to monitor and forecast extreme events.

Roxy Mathew Koll, scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, cites the examples of cyclones Fani and Amphan which intensified from “weak” to “severe” status in less than 24 hours.

“State-of-the-art cyclone models are unable to pick this rapid intensification because they do not incorporate the ocean dynamics accurately. Since ocean plays a huge role in supplying the heat and moisture for the cyclones [and monsoon], gaps in ocean data prevent us from forecasting the intensification of cyclones accurately,” says Koll.

Covid-19 was a huge blow for the observation systems. “Most of the monitoring systems require yearly maintenance, but due to Covid-19, the ship cruises that service these ocean instruments did not happen as expected during the last two to three years. As a result, many of these monitoring systems are now not relaying data,” Koll rues.

Baseline data is fundamental for companies to understand their current environment performance and then set targets, including identifying initiatives that they would like to undertake towards their net-zero goals, says Satish Ramchandani, co-founder of ESG tech firm Updapt CSR.

A lack of data, he elaborates, means their inability to enhance operational performance and disclose ESG performances with key market participants, such as investors, rating agencies, lenders, customers and regulators, thereby impacting their balance sheet performance.

“Calculating Scope 3 emissions is one of the biggest challenges that companies struggle with. For smaller companies, even calculating other climate indicators around Scope 1 and 2 can be difficult,” he adds. Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions categorise greenhouse gas emissions by businesses, directly or indirectly.

Data Gaps Initiatives

The global financial crisis that struck in 2007–08 laid bare wide gaps in availability of data, leading to the launch of the first phase of the Data Gaps Initiative (DGI-1) by the G20 countries in 2009. The group endorsed a total of 20 recommendations aimed at addressing data gaps. After the conclusion of the first phase in 2015, DGI-2 was launched with the objective to “implement the regular collection and dissemination of comparable, timely, integrated, high quality, and standardized statistics for policy use”, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), one of the partners in DGI. The second phase concluded in 2021.

“The G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (FMCBGs) recognizes that improving data availability and provision, including on environmental issues, is critical to better inform policy decisions,” Louis Marc Ducharme, director of IMF’s statistics department, said in February last year.

“Inclusion of climate change into the DGI will further intensify the efforts of various nations and institutions towards framing and execution of policies with the objective of having climate metrics,” says Ramchandani.

One of the key priorities of the new G20 DGI is to improve the quality of climate data, including efforts to standardise data collection and reporting methodologies as well as improve the accuracy and completeness of the data, besides building the capacity of countries to collect, manage and use climate data, the IMF has outlined.

Towards Solutions

Data pertaining to ESG performances of businesses has been a challenge. Though the past few years have seen increased traction at principle and process levels of enterprises to track and monitor climate and other sustainability-related data points, a continued push along with adherence to environmental mandates by the Central Pollution Control Board will be critical, says Ramchandani.

Global standards like global reporting initiative (GRI), business responsibility and sustainability reporting (BRSR) and review mechanisms at the management and board level can help organise and assimilate data. “Digital ESG solutions can solve these issues for businesses wherein data can be tracked, analysed and reported seamlessly with automation, including GHG accounting and supply chain assessments,” Ramchandani adds.

At the governance level, climate change data can assist policy makers in designing policy frameworks and regulations to help countries transition to a low carbon economy. For that, Kedia says, it is important to collect more information not just in terms of temperature and precipitation but also local environment and socio-economic data and build for climate impact modelling considering the infrastructure and socio-economic variables.

“Without understanding spatially and temporally disaggregated impacts of climate change, it will be difficult to design strategies for climate adaptation and loss and damage,” she adds.

Data disclosure and data sharing are central to having a standardised and effective action plan. “The Global South can (as the Global North) prepare disclosure regulations which oblige companies to disclose their GHG emissions, amongst other indicators. This fills important data gaps and urges companies to deal with the issue,” says Hessenius of Climate & Company.

He stresses on the importance of mandatory regulation as research has unambiguously proven that voluntary initiatives are not that effective. Hessenius acknowledges the sensitive nature of climate finance as a subject in the past climate negotiations but feels that such finance coming from developed countries can play an important role in filling data gaps. “Europe and the United States alone are responsible for more than 50% of global, accumulative GHG emissions. Even though the proportions are currently changing—for example, China’s accumulative share has doubled over the past 20 years—the Global North still bears a disproportionate responsibility in tackling the climate crisis,” he says.

Speed: The Key Determinant

India’s strides in the digital space have been noteworthy. The draft National Data Governance Framework Policy aims to make non-personal data and anonymised data from both government and private entities available for research and innovation. The National Data and Analytics Platform makes government data more accessible. The India Digital Ecosystem of Agriculture, which compiles agriculture-related data, might hold the potential to impact the sector. However, there clearly is a need for more action.

For instance, India is the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases globally, but the nation’s capacity to precisely measure and quantify its emissions is lacking. This makes it challenging to monitor the reduction of emissions and hold offenders accountable.

A significant lack of data has corresponded to a lack of investment toward achieving the environmental dimension of the SDGs, according to the UNEP. For India to fulfil its climate action commitments, it will need to do more, and quickly, to plug these gaps. The journey is long and the world is well past the “baby steps” phase.