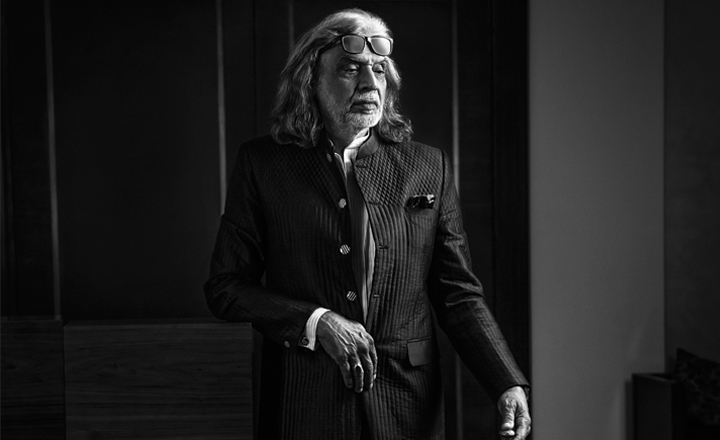

One cannot not know Muzaffar saab. He is, after all, the one who immortalised Rekha on screen with one of Hindi cinema’s greatest films, Umrao Jaan. But the genesis of Umrao Jaan is far deeper than just a great script and scintilliating dances. It’s about the nostalgia and pain about slowly losing the famed Awadhi culture, which was at its apogee during the reign of Wajid Ali Shah. “Around 1857, Awadhi culture was something you can’t even imagine,” says Muzaffar saab. “The language, the poetry, the music, the dance, the humour, the clothes, the cuisine. In India, there were very few places which could boast of such refinement.” He said that the British rule made people look down upon their own culture, then came Partition, and the end of the zamindars’ rule, which further led to a dissolution of that era. “People were migrating from there to the big cities, and that is what I have shown in my film Gaman,” he says.

He was lucky that his own father the late Raja of Kotwara, upheld his heritage and dynasty. “My father was a very futuristic man, far ahead of his times, with a progressive and humanistic approach to life,” says Muzaffar saab. “He also stood up for secular values, and opposed fundamentalism.” The late Raja saab had done his PhD on the first Kotwara rulers of Gujarat, who were Hindu, the Chawa rulers. “He was into history and conservation,” he says. “He had a great sense of record; he kept newspaper cuttings since 1915, as a boy. These are the few things I imbibed from him, the sense of history, record, and balance.” His father, educated in Edinburgh from the age of 14-24, was also an independent MLA until he became chairman of the UP Assembly. He looked at audiovisual education, hydropower, traffic planning. “His last wish was that no one in his area should remain nanga-bhooka, that no one should be poor and hungry; I imbibed this from him.”

From his mother Muzaffar saab got the legacy of craft, which he continues with his couture label Kotwara with his wife Meera. “I see a strong convergence between the values of my father, which is dealing with the rural situation, and the bigger picture, how craft can empower people.” Today, his label provides employment to around 300 people in his home village of Kotwara, who create the intricate chikankari embroidery the region is known for. “I have a lot of craft going on there, and my dhurries and shoes are being made there,” he says.

He’s also been focusing on music and kathak dance. He’s also got his Rumi Foundation that puts up different music Sufi music festivals. “Festivals aren’t easy to do, as people don’t want to commit,” he says. “At least I have some good people like Dr Karan Singh, who’s my chairman; he believes in what I am doing. Sufism is another area we believe can bring oneness of the human race.”

“I’ve used music in my films too,” he says. “I’ve done a lot of ballets on kathak, and taken it to another level of storytelling. The next step is to get people to understand the whole experience of Lucknow. I could showcase it in a museum, or even a virtual domain, or share it in Kotwara House, Lucknow. I’m going back to sustainability, to what my father said, that no one should remain nanga-bhooka, simplistically put, but it’s a complex journey.”

After his last release Jaanisar, are there more films on his mind? “Yes, I want to make a film on Rumi, which I’ve been working on,” says Muzaffar saab. “I’ve done four films on craft, so I am doing little things, whatever comes my way, and some things reach a bigger horizon.” Sounds like a visionary to us.