The Ovarian Lottery

By Warren Buffett’s own admission, his time and place of birth contributed to his success — in the past eight decades, the United States has gone from strength to strength, growing from a $91.2 billion economy in 1930 to $15.7 trillion in 2012. Buffett explains this in The Snowball. “Imagine there are two identical twins in the womb, both equally bright and energetic. And the genie says to them, ‘One of you is going to be born in the United States, and one of you is going to be born in Bangladesh. And if you wind up in Bangladesh, you will pay no taxes. What percentage of your income would you bid to be the one that is born in the United States?’ It says something about the fact that society has something to do with your fate and not just your innate qualities. The people who say, ‘I did it all myself,’ and think of themselves as Horatio Alger — believe me, they’d bid more to be in the United States than in Bangladesh. That’s the ovarian lottery.” Buffett says the fact that he was born in 1930 in the United States as a white male was winning the ovarian lottery. “I had all kinds of luck… I’ve had it so good in this world, you know. The odds were 50-to-one against me being born in the United States in 1930. I won the lottery the day I emerged from the womb by being in the United States instead of in some other country where my chances would have been way different.”

Who’s your daddy?

Warren’s father Howard Buffett was instrumental in shaping his values, building on the mid-Western culture of modesty and humility. Buffett Sr, a stockbroker who later ran successfully for Congress, was a man of high integrity. In the year after he was voted into power, the government announced a pay hike, which he refused. Jeff Matthews, founder, Ram Partners, says, “When his father got to Washington, he returned the pay increase to the Treasury saying ‘I was elected at the old pay and I am not going to take the pay increase.’” Integrity and humility are two virtues Warren Buffett, too, embodies.

Graham, the guru

Buffett went to Columbia University for his Masters degree after he read Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor at the Omaha public library when he was 19. Also called the ‘father of value investing’, Graham coined the term ‘margin of safety’, which became the bedrock of the value investing philosophy and also the foundation for Buffett’s investing framework. Over the years, while Buffett has developed his own distinct philosophy, he has not deviated from the underlying principle of buying an asset at a substantial discount to its intrinsic worth as preached by Graham. Buffett also worked in Graham’s partnership firm, Graham-Newman Corporation, between 1954 and 1956 before setting up his own partnership. He calls The Intelligent Investor the best book he has ever read and still considers it a must-read for every investor.

Changing course

After an extremely successful stint at the Buffett Partnership, delivering returns of 29.5% compounded, Buffett decided to close down the partnership and return the money to investors in 1969. Despite his fabulous performance, he took this bold decision, citing “inability to find bargains in the current market”. He liquidated all shares held by the partnership, except Berkshire Hathaway, a textile company he had systematically taken control of. Buffett qualifies his purchase of Berkshire as the “dumbest” stock he ever bought but then turned it into his famed investment vehicle. When Buffett bought into Berkshire, its textiles business was ailing, but he managed to revive the company under the able stewardship of CEO, Ken Chace. But Buffett also read correctly the winds of change affecting the textiles business, so he quickly changed direction and invested its cash flows into other, more lucrative businesses, including insurance.

Recognising the power of float

In 1967, Buffett bought into an insurance company called National Indemnity at a substantial premium to the prevailing market price. He thought of insurance as a business that provided “free” cash to invest as long as the firm did not make any underwriting loss. Buffett also bought into GEICO when the firm lost more than 95% of its value because of serious underwriting losses, but a new CEO was trying to revive the company bringing back the underwriting discipline it was once known for. Between 1975 and 1980, Buffett invested about $45 milion into GEICO, raising his stake to 33%, as he knew the company had a low-cost structure (it directly sold insurance to customers and, hence, its operating cost was 15 cents a dollar compared with 24 cents to a dollar for competition) and with the new management it could do better. Over the next 15 years, by 1995, Buffett’s investment had grown to $2,393 million, a 51% stake as the company also bought back shares. Berkshire finally bought the remaining 49% in January 1996 for $2.3 billion.

Using the insurance structure as his investment vehicle is really Buffett’s masterstroke as it provided an implicit leverage without the firm having to actually borrow any money, bolstering overall returns. This “float” is estimated to have added nearly a third to Berkshire’s annual returns.

Finding the right partner

Charlie Munger, vice-chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, has been Buffett’s partner and confidante for 54 years. Munger was instrumental in making Buffett see the merits of focusing on high-quality companies and paying up for it.

Munger meeting Buffett was pure serendipity. Buffett’s neighbour Dorothy Davis and her doctor husband were impressed enough to ante $100,000 when Buffett started his investing sojourn. Dr Davis felt Buffett’s temperament was uncannily like that of Munger and finally introduced the two at a dinner party in 1959. From there on, the two communicated regularly, sharing investing ideas and even ended up holding the same companies in their portfolios. Writer Janet Lowe says, “They hit it off instantly because they both have a take-quick-action kind of brain.” The association was finally cemented in 1978 when Munger became BRK vice-chairman and then chairman of Wesco Financial in 1984. Before they joined forces on Buffett’s insistence, both managed money separately. Munger’s investment partnership compounded at an average 19.8% between 1962 and 1975, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average over the same period returned 5%.

Quality over numbers

See’s Candies, a California-based candy company, was the landmark investment that marked the departure of Buffett from a pure quantitative process that Graham advocated to a quality-focused approach — the concept of ‘moat’, in Buffett parlance. Buffett bought the company on Munger’s recommendation, at a price far higher than what he had paid for any stock till then. He paid $25 million, or 6X operating income, in 1972. Over the next 39 years, See’s Candies brought in pre-tax earnings of $1.65 billion. See’s competitive advantage was unleashed after Buffett initiated a more aggressive pricing strategy commensurate with its quality of products. Buffett has said, “If there was no See’s, there would have been no Coke,” highlighting the significance of this investment.

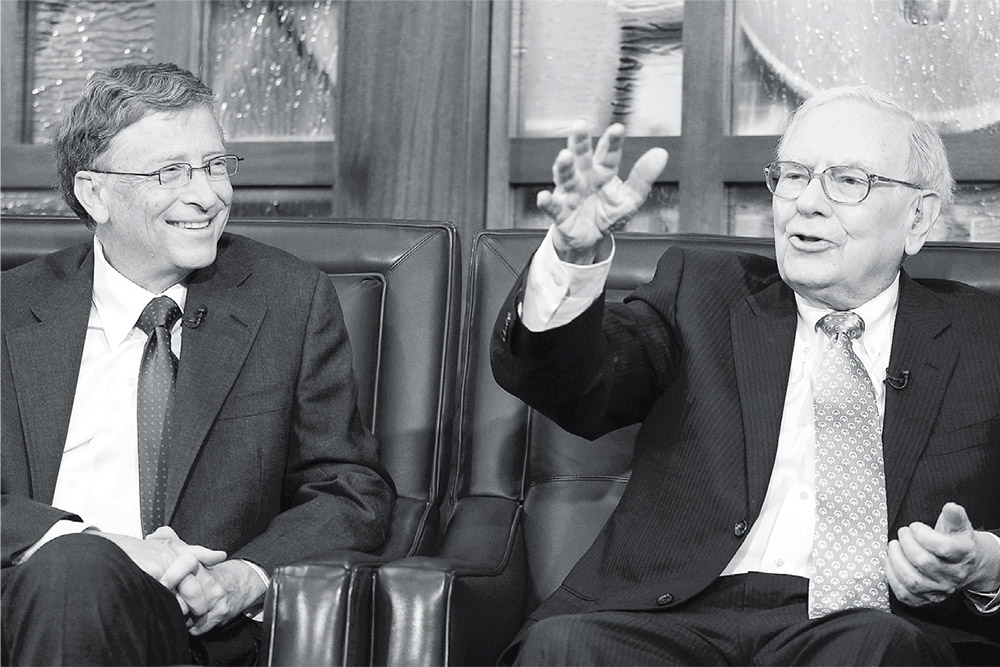

Giving back

In 2006, Buffett decided to give away 98% of his fortune to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. But then, his attitude to money is quite unique. “Wealth is just a bunch of claim checks on the activities of others in the future. You can use that wealth in any way that you want to. You can cash it in or give away. But the idea of passing wealth from generation to generation so that hundreds of your descendants can command the resources of other people simply because they came from the right womb flies in the face of a meritocratic society,” he says in The Snowball .