It is calm and quiet at Aurobindo Pharma office in Hyderabad’s Kondapur area. As we step into one of the meeting rooms, it is hard to miss a few stern-faced foreigners moving around. They are busy poring over files and make limited conversation. “This is a routine USFDA audit,” says M Madan Mohan Reddy, the company’s director, in a hushed tone. As he settles down for a chat, we think back to the number of pharma companies that have received FDA warnings in the past year. Unsurprisingly, Reddy begins by talking about an episode in mid-2011, when his company received an FDA quality-warning letter for non-sterile products at its antibiotics manufacturing plant in Hyderabad. “It was a big setback but also a learning experience,” Reddy admits.

FDA visits seem to be happening at a discomforting pace for Hyderabad’s pharma companies. This has made small and large players equally nervous about business, as exports to the US — governed by FDA regulations — continue to be the biggest revenue driver for pharma firms. What’s worse, FDA audits aren’t the only worry on pharma companies’ mind right now. Dumping by Chinese companies, infrastructure woes and lack of skilled manpower — all these factors have hit Hyderabad hard, challenging its positioning as a low-cost producer of drugs. That’s a little surreal when you consider that, with a turnover of Rs.40,000 crore, Hyderabad has come to be known as the drug capital of India, contributing a third of the country’s total drug production. Hyderabad houses more than 250 bulk drug-manufacturing units, in addition to pharmaceutical majors such as Dr Reddy’s and Divis Laboratories.

Coming up short

The quality challenges have been brewing for a while now. In November 2015, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories received a warning letter for inadequate quality controls at two of the company’s active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) plants in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana and at its oncology formulations facility in Visakhapatnam. A few months ago, in July, the European Union had banned 700 drugs for which clinical trials were being conducted by GVK Biosciences, citing possible manipulation of trials. As companies grow and launch more products, they become more vulnerable to FDA inspections, says Venkat Jasti, chairman and CEO of Suven Life Sciences, a Rs.530-crore entity. “Earlier, there would be the odd FDA check or inspection every three years or so, but now it is not unusual to hear of it as often as every quarter,” says Jasti. He adds that the number of times FDA officials visit Hyderabad has gone up four times over the past three years. Expectedly, interacting with the eagle-eyed FDA is not easy. “A large number of pharma entrepreneurs here are still very naive when it comes to dealing with the FDA. Smaller players with a turnover of less than Rs.100 crore are more vulnerable to regulatory action since they don’t invest in compliance,” explains Jasti. “It’s also a mindset issue — companies do not mend their ways until the FDA comes calling.”

However, larger companies have tackled this problem head-on. “In 2011, we didn’t have a quality management system in place. Today, we understand the need for transparency,” says Reddy. The sentiment is echoed by Abhijit Mukherjee, COO, Dr Reddy’s. “The approach today is to invest in compliance. It is necessary to put resources and talent in that direction.” According to Aurobindo’s Reddy, his biggest investment is in a large quality team that is now 30-35% of the overall workforce, up from 20% in 2011. Aurobindo has also set up management systems for quality, lab information and documentation. “We have invested in people and systems — the idea is to take everything online and quickly identify potential problems,” says Reddy.

However, larger companies have tackled this problem head-on. “In 2011, we didn’t have a quality management system in place. Today, we understand the need for transparency,” says Reddy. The sentiment is echoed by Abhijit Mukherjee, COO, Dr Reddy’s. “The approach today is to invest in compliance. It is necessary to put resources and talent in that direction.” According to Aurobindo’s Reddy, his biggest investment is in a large quality team that is now 30-35% of the overall workforce, up from 20% in 2011. Aurobindo has also set up management systems for quality, lab information and documentation. “We have invested in people and systems — the idea is to take everything online and quickly identify potential problems,” says Reddy.

Chinese onslaught

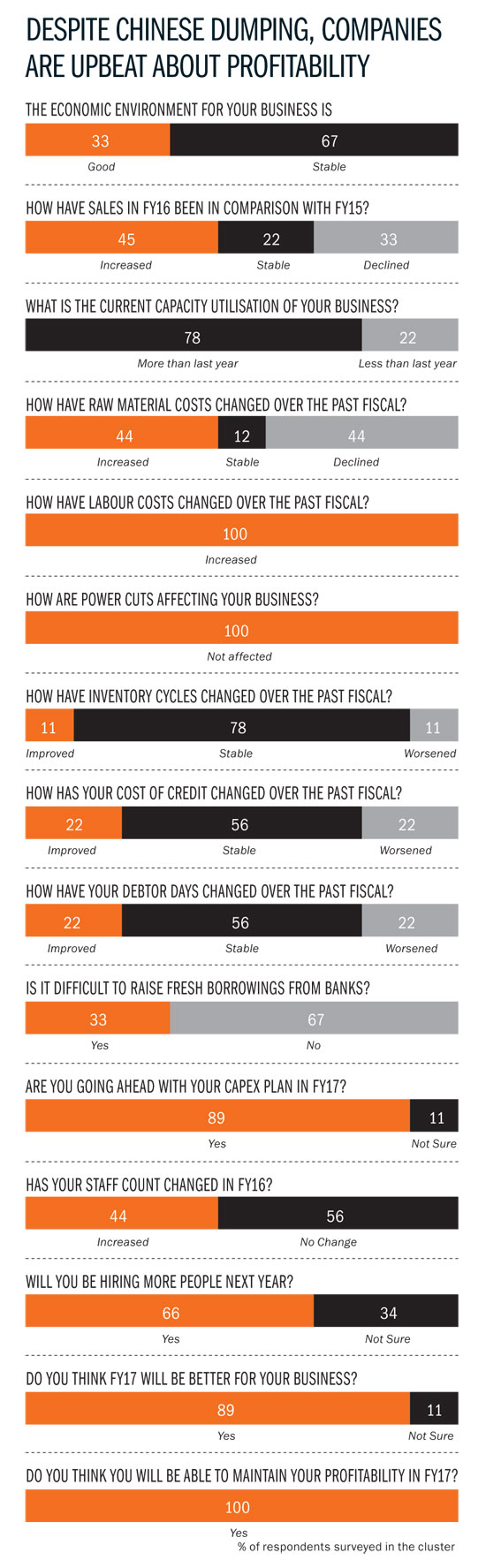

Things have never been this bad in this cluster — it is estimated that close to 100 units are in financial duress of some form or the other. Much of this is due to the Chinese onslaught; API manufacturers in the city have faced stagnant prices for at least five years now because of cheaper imports from China. “That has forced a lot of people to shut shop.” Take the case of Surya Kumar Sikha, whose Vensa Laboratories has been shut for over a year-and-a-half now. Sikha had bought an existing plant in 2011-12 and invested Rs.4 crore in anticipation of orders from Divis Labs and others. The plant — at Pashamylaram, 50 km from Hyderabad — was to manufacture bulk intermediates for analgesic drug Ketorolac. Just as Sikha finished his investment, the Chinese dumping problem hit its peak: Sikha’s potential buyers got 25-30% cheaper bulk drugs from China. “While the infrastructure was ready — 40 people had been hired — we had no orders in the pipeline,” laments Sikha. Banks then refused to support the project and it was difficult to acquire new customers. Sikha, who came from a petrochemical background, paid a heavy price for being just an intermediate manufacturer.

With the Chinese onslaught not showing any signs of abating, there are a couple of things that bulk drugs manufacturers are doing to stay in business. One, they are focusing on niche segments, that is, drugs with smaller volumes. Given the scale at which the Chinese operate, it becomes unviable for them to manufacture smaller quantities, which is why they target larger segments like antibiotics. So, local bulk drug manufacturers enjoy better pricing leeway in niche segments and can compete effectively. Two, they are integrating backwards and getting into manufacturing intermediates, which is a couple of steps before the bulk drugs stage. The idea behind this backward integration is to control costs and the supply chain better and have a slightly more comprehensive, better-quality product offering. This value proposition, companies feel, will be the saviour, as opposed to competing only on price. Once you take away the price advantage, India scores over China on quality. So, at the same price, buyers are likely to go with integrated bulk manufacturers in India.

Getting the approvals to manufacture intermediates is a time-consuming process, but one that will hold these manufacturers in good stead in the coming years. B Ananda Reddy, who runs a Rs.100-crore business spread across two entities — Chromo Laboratories and Gensynth Fine Chemicals — had to go through a three-year struggle before “finally getting FDA approval to manufacture intermediates for hypertension. It was a struggle to convince the banks, get loans approved and set up the facility. But we were very clear that we wanted to have a comprehensive portfolio of products. We are better at technology, so drug intermediates is where we have

to focus”. Srinivas Isola, managing director of the Rs.130-crore Sreepathi Pharmaceuticals, adopted the same tack. “We decided to take the backward integration route six months ago. We had no choice — it would have been very difficult otherwise,” he admits. He is hopeful about the next fiscal. “We will now go ahead with our capex plans.”

Bulk drug makers can’t compete effectively unless infrastructure bottlenecks are addressed. For now, one overarching problem has been resolved. “The power situation was really bad in 2014. There would be no power for four to six hours each day. It was really difficult for smaller companies to survive. That has changed drastically,” says Aurobindo’s Reddy. Now, there are hardly any power cuts. “It is very manageable — we store five kilolitre of diesel today compared with 60 kilolitre in the past,” he adds. More important than the savings on power back-up have been the productivity gains on account of continuous power. “Switching a machine on and off would mean a loss of at least 450 tablets. Today, we have fewer rejected products,” Reddy explains.

But power isn’t the only issue that units face. Jayant Tagore, president, Bulk Drug Manufacturers Association (India) says inadequate infrastructure is a legacy issue in India. “In China, infrastructure is shared because they have a cluster approach to manufacturing. This adds significantly to their competitiveness. Their selling price is thus at least 15-20% cheaper,” he points out. Seconds PV Appaji, director general, Pharmaceuticals Export Promotion Council of India, “Hyderabad has come a long way so far, despite the bottlenecks. But now, as the global scene gets tougher, we need to address the infrastructural challenge to remain competitive and grow further.”

City of dreams

But the industry does have a potential game-changer waiting in the wings in the form of the Pharma City at Mucherla, around 50 km from Hyderabad. Spread over 11,000 acres, this estate is touted to be a self-contained facility comprising a pharma university, a research centre and residential townships. That will also address the lack of skilled labour. “Talent is hard to come by. The problem is getting very acute now,” points out Mukherjee. However, the industrial park is at least three years away, with a whole lot of clearances still pending. Meanwhile, Visakhapatnam already has a pharma city and there is a real danger of companies moving there. Global majors such as Japan’s Eisai Pharma and US’ Hospira already have a presence there, along with several other Indian companies. So far, companies have abstained from relocating from Hyderabad because it has historically had a large pool of skilled workforce. Now, Pharma City needs to take off quickly for companies to stay on and thrive. But Mukherjee counters, “In the end, infrastructure is only an enabler. It is ultimately left to entrepreneurs to seize opportunities wherever they exist.”

There are more compelling issues to be dealt with that aren’t restricted to Hyderabad alone. While regulatory challenges remain in the US, emerging markets such as Russia and Venezuela are playing spoilsport as well. “The massive hit on their currencies has had a negative impact on purchasing power and that is a cause for worry,” explains Mukherjee. A stronger rupee against these emerging market currencies has hit margins. “Venezuela is in dire economic straits and we are not able to repatriate any money. This has forced us to cut sales, although there is demand. These are economies that are heavily dependent on oil exports and the recent months have been rough on them,” he adds. Still, the situation at the city’s large pharma players is encouraging. For instance, capacity utilisation levels have increased at Aurobindo by as much as 25-30%. “That alone has raised our margins and allowed us better economies of scale. We manufacture 850 million tablets each month at the Kondapur factory and that will touch 1 billion over the next six months. We have a capex plan of roughly Rs.300 crore for FY17,” says Reddy. Jasti of Suven is also positive about the future and is investing more and increasing staff strength this fiscal.

Then there are companies like Natco Pharma, a leading player in oncology and hepatitis, which is steadfastly focusing on product pipeline and investing in research. “There is a lot that can be done; it is really up to us. Pharma still is a very creative business,” says Rajeev Nannapaneni, vice-chairman and CEO, Natco Pharma, which has been active with product launches. Natco recently signed an agreement with Gilead Sciences and with this first-mover advantage has launched the Sovaldi generic drug for Hepatitis C. It will soon sell generic drug Natdac, a version of Bristol-Myer Squibb’s medicine for Hepatitis C. Another optimistic statement comes from Aurobindo’s Reddy.

“In India, we still have the cost advantage and the technical expertise. It is only a matter of combining these factors and if we do that, we will be fine,” he says. “The city has had a rich ecosystem in terms of the total number of companies and a skilled manpower base,” points out Nannapaneni. “We just need to strengthen it.” By the looks of it, the big fish in Hyderabad are sitting pretty for now, while the jury’s out on how the story for the minnows will play out.