You have brains in your head and feet in your shoes, You can steer yourself in any direction you choose!

That’s not even easier said for autistic children, as such kids are often non-verbal or minimally verbal. For them, communicating even basic wants is an uphill task. But Dr. Suess’ words have long been used to tackle learning disabilities. And as David Yoder says, “No child is too anything to be able to read and write.” These were exactly Ajit Narayanan’s thoughts when he came face to face with these kids for the first time. “It’s not like they had nothing to say, but saying it was a challenge.”

Having just returned from Silicon Valley, Narayanan says, “I knew with the right kind of technology and applications, we could help the kids communicate.”

Finding the voice

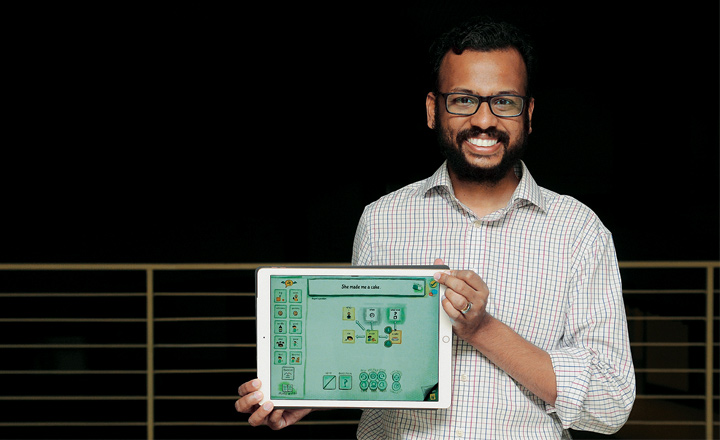

Narayanan was back in his alma matter IIT Madras, after returning from the US. Some of his professors were helping out a school called Vidya Sagar that worked with kids, who suffered from learning disabilities. “They roped me in to meet the director of the school. I spent some time interacting with kids with cerebral palsy and autism.” The interactions, Narayanan says, helped me understand the disability. It took many a prototype, but Avaz, in the form, of a lightweight tablet, came into being in 2010.

With pictures and words on the tab, the kids had found a way to communicate, almost independently. But even though the tablet came at a fraction of the cost of other such devices, the hardware part was tough to execute. So, when Apple launched the first version of iPad, Narayanan, CEO, Invention Labs, figured it would be more cost-effective to just ride the wave. By launching an app, Avaz would not just reach out to more customers, but the hassles of manufacturing would go away.

When the app was launched in 2012, priced at $200 for the overseas markets and $100 in India, Narayanan says, “It was like a rocket ship taking off. The adoption outside India was phenomenal.” So much so that US went on to become the company’s largest market. It still is. “Until the launch of Avaz, all augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices available in the US were mono-lingual. The US has a large Spanish speaking and Asian population so the product was a natural fit for them. Even today, there is nothing in the market that is as easy to use as Avaz,” says Lucas Steuber, a speech pathologist and co-founder and development director, Aim High Ignite.

While none of this technology existed in India, countries like Denmark and the US had access to AAC devices but as Steuber says Avaz was better. Narayanan thus started getting a lot of requests from several non-English speaking countries. The CEO says when he showed a demo to the head of the autism society in Denmark, the lady insisted for a Danish version. “Now, it is our second largest market after the US,” shares Narayanan.

How does Avaz work? Autistic kids can’t really grasp the meaning of words, to them it is just a random collection of sounds. Pictures, on the other hand, are easier to understand. While some kids might be able to type out words, because of motor disabilities, even that becomes a challenge. The AAC app, thus, gives children a way to communicate with a series of images, with the option to add more pictures and words.

What also made Avaz unique was that unlike other AAC devices, there was an intervention tool that helped parents act like therapists. This had special significance for India as unlike the US, which has 150,000 speech therapists, India has just 1,800. “Kids didn’t have access to technology like Avaz before, it was life-changing for them,” says Kalpana Rao, principal, Vidya Sagar, where the company’s journey began. To prove just how life-changing, the proud principal shares that one of her students is to take his 10th Board exams using Avaz next April.

Moreover, the app was already available in several Indian languages. This made it easier to replicate the process and add foreign languages such as Spanish, Italian, French, Danish and others. Today, around the world, about 35,000 kids with varied speech disabilities use Avaz, with more than 60% of them in the US, 15% in Denmark, 10% in India and the rest spread across the world.

Stringing words together

But while Avaz had created an impact, Narayanan received a peculiar feedback from speech therapists across the world. Almost 80% of kids using Avaz were speaking just one word sentences. For instance, if the kid wanted water, he/she would say just “water” instead of “I want water”.

“This was a serious limitation because when these kids need access to higher education and employment, you need them to know the language. It’s not enough to just know words,” says Narayanan. But while the CEO recognised the problem, the solution presented a big challenge. “Words have a certain abstractness which you can solve with pictures. But grammar is even more abstract, thus it was difficult for the kids to handle,” he adds. And by his own admission, there was nothing in Avaz to tell the kid if the sequence of images was right or wrong.

“Grammar is incredibly powerful because it allows us to convey an infinite amount of ideas with a finite vocabulary.” Narayanan thus fretted for a long time. How could he impart grammar skills to these kids? He found inspiration from two sources. One, an ancient scholar called Panini, who had set the lingusitic standards for Sanskrit, by summing up in about 4,000 rules the science of phonetics and grammar. Following Panini’s rules, no matter how complicated the sentence, you were guaranteed to get a grammatically correct sentence. “He converted Sanskrit into a computer language capturing all the intricacies. It gave me a sense of direction. Why not let the computer generate the language instead of forcing the kid to generate it. In Avaz, we were not forcing the kid to generate the speech,” says the founder.

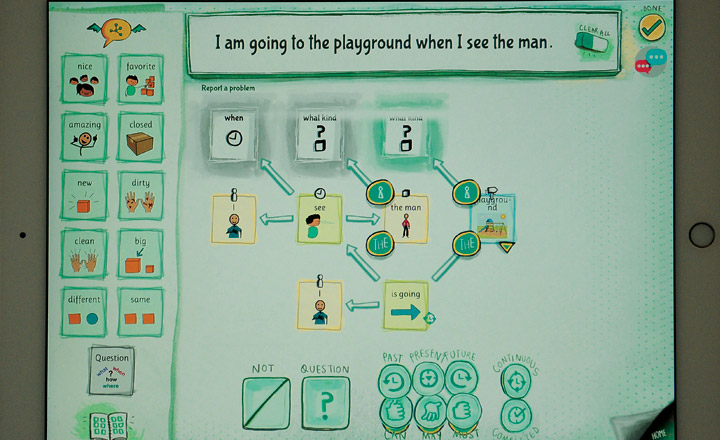

His other inspiration came from watching a mother interact with her austistic child. The child had just uttered the word “eat”. But the mother had figured out what the kid wanted — An ice cream on the way home — by asking a series of questions. “What the mother had done was incredible; she got the child to communicate without any grammar. She didn’t have to know the sequence of the words. She had done it through question-answer pairs by asking her what she wanted to eat, when and where. Both these processes gave me a sense of direction about building the language, the algorithm and how to map it with question-answer pairs so the computer can arrive at the right sequence.”

Soon, the kids had FreeSpeech. Like the spell check smoothes out the errors in the text, FreeSpeech helps autistic kids communicate complicated sentences. “FreeSpeech is the easiest way to learn the structure of any language. While other apps teach you rote phrases that maybe useful in some context, FreeSpeech allows users to create sentences in any context,” says Steuber, who collaborated with Invention Labs on FreeSpeech.

Narayanan soon realised that the map they had created could hold true for any language. FreeSpeech thus could have wider applications as a learning app. It need not be restricted to those with learning disabilities. But aren’t popular apps like Duolingo doing that? Narayanan says the fact is that with these apps the drop-off rates are high as they are not immersive enough. With FreeSpeech, he says, users are not learning mechanically, struggling with the words in the native language, but constructing sentences directly. Hence, it is easier to pick up a language be it Hindi, German, Spanish or French because the engine follows the data structure of thought and not language.

Launched in March this year, the app is available on the Apple app store for $10 now, and has already seen thousands of downloads. Invention Labs plans to introduce it in India on Independence Day for around Rs.200. Post that, it will make take it to China, Russia, Brazil, Korea and Japan.

To achieve the language breakthroughs that Invention Labs did, it raised about $500,000 from Inventus Capital and Mumbai Angels in 2014. “Speech and language learning is a very difficult space to crack because there is a lot of abstraction involved. Avaz and FreeSpeech are the closest products we have in the market to learn a language in the most natural way possible. It has managed to capture the nuances and intricacies of many languages,” says Parag Dhol, managing director, Inventus Capital.

Considering that in America alone, one in 66 kids are born with some form of autism, Narayanan’s invention can’t be undermined. And with FreeSpeech, it has widened its own ambit. “We got into this business to give children who had speech disabilities a voice. We have used technology to cater to a larger audience and solve the problem of learning a language, helping people achieve a better standard of living. Language is the best thing that we humans have created. It entertains, enlightens and most importantly empowers,” ends Narayanan.