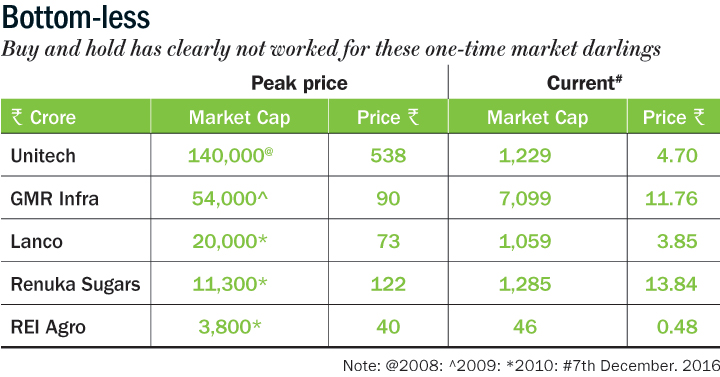

To catch a falling knife’ is a popular market saying and is thrown about when one wants to buy into a stock that has plummeted. The underlying belief being that it will bottom out and reverse trend soon. In the current scenario, there are a lot of stocks that have lost 30-50% of their market cap and seem attractive when compared to their glory days. The table Bottom-less is representative of the truism that low price does not necessarily equate value.

Nilesh Shah, CEO, Envision Capital Management explains. “Price is just a reference point. It says nothing about the intrinsic value of a business or how much a business is worth. So, a low price does not mean a business has huge value. When a stock falls, one needs to figure out if the fall is temporary or due to a permanent impairment in the business,” he says.

Take, for instance, REI Agro, which was once the world’s largest rice processing company. The promoters held 47% while FIIs held in excess of over 40% in 2013, when the stock was quoting at Rs.10. While that might have seemed low-priced, the stock has continued its slide and now trades at Rs.0.50 after a fraud allegation against the promoters. Lanco Infratech is another example. It traded at Rs.75 in 2011 and had a market cap of over Rs.20,000 crore on an equity of Rs.4,600 crore. However, losses incurred due to high interest cost have knocked its price down to an all-time low of Rs.4.

In debt we trust

Investors often hope to find diamonds in the dust, but a happy ending is never guaranteed. If one looks at Unitech, its equity is over Rs.10,000 crore and debt around Rs.5,200 crore, but its market cap is Rs.1,200 crore. In FY16, the company was not able to cover its interest cost of Rs.347 crore and hence, incurred a loss of close to Rs.1,000 crore. Though the developer has close to Rs.4,000 crore worth of inventory, including land that is currently valued at Rs.3,500 crore, the market is skeptical about the optimum utility of the inventory owing to hurdles in terms of approvals and execution of projects. Besides, its contingent liability of Rs.11,100 crore adds to its woes.

GMR, too, is stuck in a debt trap because of a lack of cash flow from its assets and an inability to cut down on debt through asset sales like the Island Power Project, Istanbul airport, coal mines, three road projects and two transmission assets. It did reduce its liabilities by Rs.7,600 crore, but the situation isn’t a lot better, given its annual interest payment of Rs.4,000 crore. GMR’s absolute debt has grown from Rs.49,952 crore in FY15 to Rs.51,600 crore in FY16, compared to its equity of Rs.5,944 crore.

While the nature of its business allows for high leverage, because of negative cash flow from operations and a relatively small networth, the risk is high. To improve cash flow, GMR will have to sell assets and drastically cut down its debt.

“In asset-heavy companies that are struggling with debt, you need to see if there is impairment in those assets. If there is impairment, the first markdown is always taken by the equity shareholders and the second by debt holders. After accounting for impairment and debt, you can decide whether there is any real value left. Even with a low price, the company might not have any value left,” says Manish Bhandari, CEO, Vallum Capital Advisors.

Past glory

Many of the low-priced stocks have reached a point where there is very little value left, despite their illustrious past. Shah explains why banking on the past might not be a good idea. “The past is useful, but it is not everything. If we are stuck to a certain price point in the past, it is possible that we might end up making a huge mistake, if the intrinsic value of that business drops simultaneously,” he says.

But, that cautionary note does not stop investors from seeking refuge in the asset replacement value of commodity companies. One-time market darling Bhushan Steel incurred an interest cost of Rs.4,582 crore, a 3x increase since FY14 on a revenue of Rs.13,000 crore in FY16. It suffered a loss of close to Rs.3,000 crore and the stock now trades at Rs.40, compared with Rs.550 in 2014. While its current market cap is Rs.900 crore, from an asset replacement perspective, its 5 million tonne capacity is valued at Rs.33,000 crore (Rs.6,000 crore per mt + Rs.3,000 crore of work in progress). However, that is less than its total debt of Rs.45,118 crore. Sticking to high debt, Shree Renuka Sugars has been incurring losses for the past five years due to its debt of Rs.9,400 crore. That figure is far more than the depreciated value of its plants pegged at Rs.7,400 crore. Shah adds that the intrinsic value of a business is extremely tentative and he corroborates it with that of Satyam, whose price dropped from around Rs.180-200 to as low as Rs.10 a share after the crisis hit the company.

Dumb play

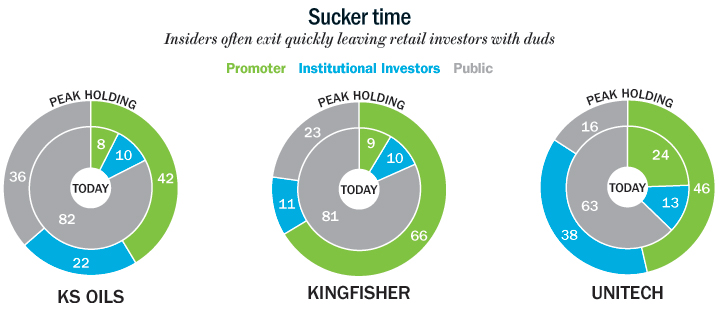

The presence of institutional investors in a low-priced stock is no guarantee that the stock will regain its past glory. We will come to that in a while, but let us first look at a lesson learnt the hard way by the retail investor (See: Sucker time). In Kingfisher Airlines, the bottom-fishing continued even as the fundamentals of the company deteriorated. After the appointment of Sanjay Aggarwal to turnaround the airline, the stock jumped from Rs.50 to Rs.90 in mid-November 2010. At that time, the promoters held close to 66% and around 11% was held by the public. However, the last holding disclosed in September 2014 showed a public holding of close to 82% compared to the promoter holding of 8.5%.

“Even when the court was issuing warrants to the promoter, who had pledged all his shares, and institutional investors were selling their stake, there were people who were buying shares at Rs.5 in the hope that someday, someone will take over. But, who would buy assets whose value was less than the liability on the balance sheet? Investors need to ask why a particular stock is trading at a low valuation. In 99% of the cases, there is a good reason for the stock to trade at the price at which it is trading,” says Daljeet Singh Kohli, head of research, IndiaNivesh. Kingfisher’s stock is no longer traded and the last tick was Rs.1.36. Kohli says that on the business front, the situation is likely to deteriorate because, in such cases, the promoters lose interest after erosion in market value and dilution of stake in the company.

GVK Power and Infrastructure, which holds assets in power, airports, road development and coal mining, is also going through a similar phase where the brunt of a markdown in the value of its assets is borne by the shareholders. Because of a delay in the monetisation of their assets, the company is under Rs.25,000 crore of debt on an equity of Rs.1,400 crore, giving it a debt to equity ratio of 18x. The situation is reflected in its current market price of Rs.5.80 and a market cap of Rs.900 crore. GVK has been forced to sell its profitable assets in the airport and road sector as against power and coal mining. Earlier, Prem Watsa-owned Fairfax Financial Holdings bought a 33% stake in its Bengaluru airport for Rs.2,149 crore. With this, GVK can only hope to reduce its debt by Rs.2,000 crore and bring down interest by about Rs.300 crore, which is considerably negligible given its FY16 annual interest expense of Rs.2,300 crore.

Like Kingfisher Airlines, KS Oils, too, no longer trades, but it had a marquee list of institutional investors in its heydays. The company traded at Rs.50 in September 2011 and had foreign investors like Baring Private Equity Partners, which owned 6.23% followed by Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs together holding 32%. After a year, FII holding steadily dropped from 27% to 19% in September 2015 and almost touched zero by September 2016. Interestingly, its promoters have also sold majority of their shares and now hold 7.54%. The remainder 92% is resting blissfully in the demat accounts of retail investors.

Kamat Hotels is another stock where institutional investor Clearwater Capital Partners has taken a huge write-off. It invested $18 million in Kamat’s FCCB, where the conversion price was fixed at Rs.225 per share. However, because of high leverage and operating losses on account of a slump in the hospitality industry, Kamat Hotels’ stock took a beating. Clearwater however took the haircut and converted at Rs.135 a share and ended up with a 32.2% stake. In fact in 2012, it bought more shares from the market (reaching 41.3%) hoping to turnaround with the reduction in debt (after conversion) and availability of CDR window for restructuring. Later, Clearwater threw in the towel selling it as low as Rs.42.

The stock currently trades at Rs.30 and Clearwater now holds just over 1%. “I do not know about individual cases, but it often happens that you have an institutional investor desperately looking to sell and it gets someone to buy its holding. These deals are backdoor, at a far lower price than the quoted price. Most of the holding goes into the hands of speculators who gradually dump it to retail investors,” says Kohli. Clearly, playing the low-priced stocks game is not for the faint-hearted. As history has shown both novice and veteran alike often confuse price with value.