Natarajan was 10 years old when poverty forced his family to discontinue his studies. To make ends meet, the young lad went to work in a fruit shop. Back in 1957, he could not possibly have known it was the beginning of an abiding passion. In 1964, he joined a Coimbatore textile mill as a spinning employee. Mills would have two shifts and he always preferred the one in the night so that he could sell fruits in the morning, carrying baskets to schools and bus stops, then graduating to a cart he would ply near the railway station. The genesis of Pazhamudir Nilayam, 33 expansive stores across Tamil Nadu selling the largest variety of fruits and vegetables anywhere in India, lies in those dusty days and sleepless nights.

Today, in the near-perpetual and sweltering heat of Tamil Nadu, customers walk into cool, spacious outlets, staffed with polite salespeople, to pick up modest pan-Indian staples like pumpkin, drumsticks and beans, seasonal rarities like tender mango, green pepper and mahali kizhangu (a medicinal root), and an array of fruits like grapes from California, rambutans from Thailand and pears from China. Families browse with children in tow, a box of strawberries joining a bag of onions in a medley of fresh, colourful produce that customers have come to identify with the chain. Natarajan, now 64, continues to work without pause, his chaste Tamil and humbling courtesy hiding the long years of struggle. This is his story.

Organic growth

In 1965, Natarajan opened his first store for fruits along with his three brothers near Coimbatore’s famous PSG College of Technology. By 1982, there were four branches and each brother took one, expanding further on his own. Natarajan’s wife, Dhanalakshmi, sold all her jewellery to help him expand to a bigger showroom. By 1985, he was selling vegetables alongside fruits in his ‘showroom’ for fresh produce. Pazhamudir [‘where fruits drop from trees’] Nilayam [‘house’] innovated in other ways its customers now take for granted.

Natarajan tagged prices at a time when fruits and vegetables were not a fixed price trade in Tamil Nadu — bargaining and fudging of weights was commonplace. He did away with the sale of fruits by the dozen, opting instead to sell by weight — till then, traders would pass off small fruit with big at the same price. He also encouraged customers pick what they liked (no objections to sifting), and introduced digital scales and computerised billing. He faced opposition from other vendors but his methods were a hit with customers.Mrs Natarajan, too, hired and trained women (another first), and watched the shops, with an eagle eye, for wastage.

The first branch outside Coimbatore was opened in Tiruppur in 1998. The textile city now has two stores. There are four branches in Puducherry, seven in Coimbatore, two in Erode, one each in Thanjavur, Pollachi, Cuddalore and Trichy. An outlet costs ₹30-40 lakh to set up, break-even follows in two years. The first of Chennai’s 14 stores opened under the name ‘Kovai [Tamil for Coimbatore] Pazhamudir Nilayam’ in 2001. The state capital is the brand’s biggest market (four more branches by April), though Bengaluru may catch up in future.

Pazhamudir also makes institutional sales to hostels, caterers and hotels. That’s been possible because of the focus on quality: Natarajan still wakes up at 4 am everyday to reach the market early. “They ask for the best quality, pay the best price, and they pay in cash, no credit,” says Anu Joy, director, Joy Fruits, fruits wholesaler in Chennai since 1969. “Mr Natarajan has made everything transparent. Now, every wholesaler wants to deal with them and some standalone shops are trying to copy them.”

Fresh thinking

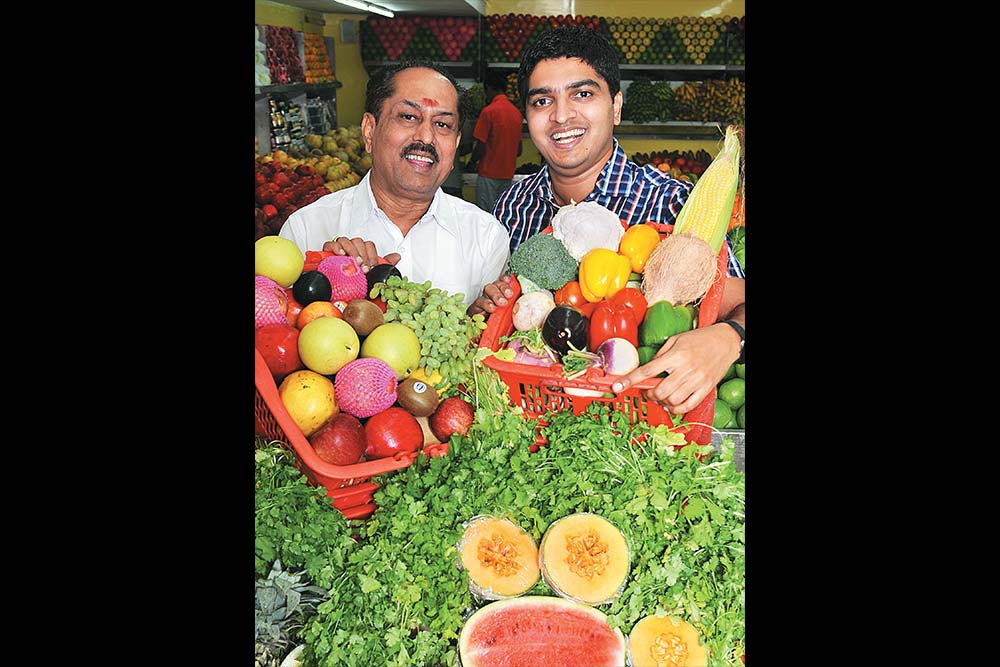

Natarajan’s son Senthil, who trained as a software engineer, became actively involved with the business in 2006. He has largely been responsible for scaling up the brand with his more outlets-more varieties strategy. For instance, if his father initially felt that Chennai could only take five branches, Senthil set his sights on 50, and if Reliance Fresh and the Aditya Birla Group’s More chains stocked 30-40 varieties of vegetables and 25 varieties of fruits, Pazhamudir ensured it had 120 vegetables and 80 fruits on its shelves. Senthil also made ‘Seasons’, a salad bar-cum-fruit juice counter, a standard feature at all Pazhamudir outlets.

As volumes built up, Pazhamudir began sourcing fast-moving produce in large quantities from big farmers and agents with pre-fixed quality norms.

“They have a strong supply chain system in place and all the people down the line are involved in quality control,” says TN Balamohan, special officer, Horticulture College and Research Institute, Tiruchirapalli. The large volumes and direct sourcing keep Pazha-mudir’s prices roughly 10-20% lower than those of hypermarkets and street vendors.

Imported produce also comes directly from sources in eight countries. “Exotic produce has a very short shelf life,” Senthil Natarajan says. “We bore initial losses in promoting fruits like kiwi and rambutans and thought of them as advertising for that particular fruit.” If initially Pazhamudir sold 10 kg of the Royal Gala apples (from New Zealand and Italy) per day per outlet, it now sells 300 kg and is the largest importer of the fruit in India. The chain expects to import 120 20-tonne containers of fruits this year.

Mark-up is about 20% on average but not on price-sensitive essentials like potatoes and tomatoes, where mark-up can be as low as 5-10%. Mark-up also depends on wastage, which is less than 1% for onions but more than 30% for capsicum. “This business has always operated on wafer-thin margins,” says Natarajan. “Operational efficiency is a must. We keep pilferage and wastage down to less than 4%, which is low by industry standards.”

Cool logic

The Pazhamudir model works very differently from the hypermarket format even though it competes directly with it. Hypermarkets need 50,000-100,000 sq ft of everything-under-one-roof, several kilometres of travel to get to and from an outlet, and storage under refrigeration both at the industrial and home levels.

In developed economies, intermodal freight transport (multiple modes of transport such as road, rail and ships without handling freight while changing modes) via refrigerated containers has dramatically changed the fruit and vegetable trade, allowing consumers to enjoy fresh produce from different parts of the world even during local off-seasons. In India, however, power is the most expensive factor in the perishable trade chain, followed by fuel.

Moreover, even in the foreseeable future, Indian consumers are not going to drive 20 km to buy vegetables. “Wherever they live, people should have a Pazhamudir nearby,” says Senthil Natarajan. Outer suburbs included, Chennai has a population of about 10 million. About 5-10% of this demographic is upper middle-class or affluent, which results in a market size of 1 million. With 14 outlets averaging 2,000 consumers each, Pazhamudir is currently serving about 28,000 people every day in the metro alone. Assuming its clientele returns to replenish supplies every third day on average, Pazha-mudir’s Chennai stores have a regular following of about 100,000 customers, leaving another 900,000 waiting to be reached. He adds, “There is no doubt that the market has potential.”

The Natarajans are happy to count judges, musicians and actors amongst their customers but they remember the bank employee who has been stopping by for years to pick up a couple of lemons, a handful of green chillies and a few sprigs of coriander every day. “The bill comes to less than ₹10 but that’s all he needs,” says Natarajan. “He, too, is my customer.”