Amul is badass. That girl mascot has earned her punk, bright-blue hair. On its website, the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) proudly says that it was born out of protest. Its ads have offended a ruling government, invited the wrath of a political party, nettled cricket czars and even taken the wind out of British Airways (or ‘Errways’ as the brand called it). Besides its tongue-in-cheek messaging, the brand has stayed on top of the game with an enviable supply chain and sensible product line.

More recently, around 2010, it has realised the market needs it to be more than clever and efficient. The market needs Amul to have more sparkle — in the form of product innovation. So, the brand is out mining diamonds. Though multiplying revenue is the focus, Amul is hoping that the new line will also keep the brand relevant.

About five minutes into our meeting with RS Sodhi, he interrupts the discussion. The MD of GCMMF (Amul) wants us to sample one of their newer launches — Irish Drink. It resembles Baileys Irish Cream, he says, “bilkul waisa hi”. It is like Willy Wonka offering the visiting children a tipple. But we take two shots of it, yes, it is served in shot glasses and he is right. It tastes like the cocoa-flavoured liqueur, except it is a fine blend of rich milk cream, coffee, chocolate, hazelnut and caramel (0% alcohol content).

Launched last summer, the 200 ml can priced at Rs.40 serves as a ‘cool’ alternative to carbonated beverages and is sold mostly through online channels. There is also Kadhai Doodh, Haldi Doodh and Camel Milk. “They have a small, but fast-growing share of our total turnover,” he says. But more importantly, he adds, they help in contemporising the brand.

Inside a glass cupboard, in its headquarters in Anand, Gujarat, is an impressive display of products that are still being tested. They include chocolate-coated almonds, chocolate nankhatai, breads and a whole range of cookies, juices and ice-cream sandwiches in a variety of flavours. While milk, ice-cream and butter continue to remain its mainstay, Amul has ventured into several utterly (butterly in some cases) delicious categories. The additional product range is impressive in its ambition — from sweetmeats such as rasmalai, rabdi and kaju katli and the darkest of dark, single origin chocolate bars to potato-based frozen snacks and biscuit packets.

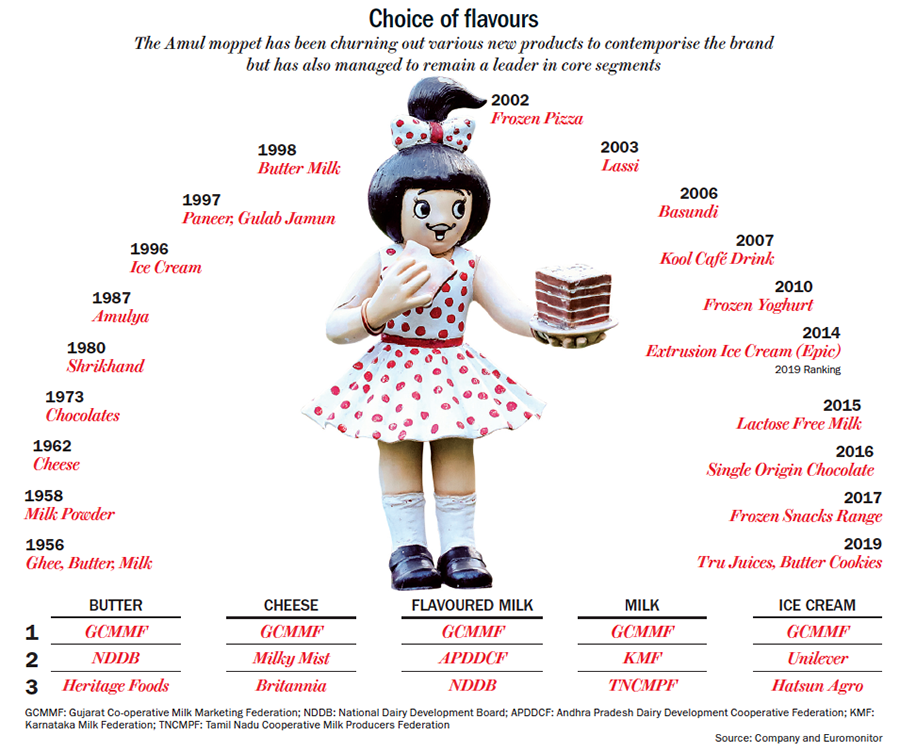

Milk still brings in 92% of its sales. But pure milk will have the lowest revenue growth, says Anil Talreja, partner, Deloitte India. So, diversification is a clever strategy (See: Choice of flavours). “With people moving away from aerated beverages and increasing awareness about lactose intolerance, there is a strong growth opportunity for dairy players. Companies need to be on their toes to get the right products in the right sizes,” he says. Harsha Razdan, partner and head, consumer markets and internet business, KPMG – India, concurs, “Milk is available in abundance,” he says. In fact, production in India has increased more than 10x since Amul was founded.

Milk still brings in 92% of its sales. But pure milk will have the lowest revenue growth, says Anil Talreja, partner, Deloitte India. So, diversification is a clever strategy (See: Choice of flavours). “With people moving away from aerated beverages and increasing awareness about lactose intolerance, there is a strong growth opportunity for dairy players. Companies need to be on their toes to get the right products in the right sizes,” he says. Harsha Razdan, partner and head, consumer markets and internet business, KPMG – India, concurs, “Milk is available in abundance,” he says. In fact, production in India has increased more than 10x since Amul was founded.

Amul’s pace of innovation picked up post 2010; till then it was launching four to eight products every year. Then it put the pedal to the metal, and began sending out 10-20 new products each year. In 2014 alone, it had 34 launches! Samir Kapur, an independent management consultant who teaches at various B-Schools in India, calls the company “an innovation factory”. “Be it their product, packaging or distribution, Amul has always had a novel approach. It talks to the older generation with campaigns like ‘Amul doodh peeta hai India’ and uses sharper advertising for the millennial consumer,” he says.

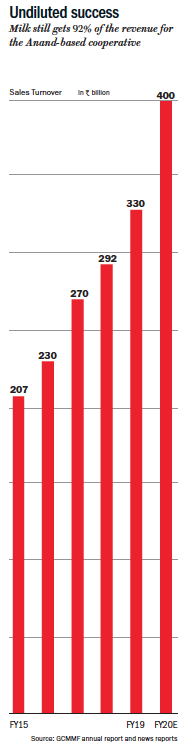

Sodhi has big plans for the newer segments. Currently they contribute 2% to the company’s revenue, but he expects it to jump to 10% in the next five years. Amul will invest Rs.6-8 billion every year to expand capacity and enter new verticals. In FY19, the company reported a turnover of Rs.330 billion and the MD is confident of hitting Rs.500 billion by FY21; and in the next ten years, the target is a turnover of Rs.1 trillion, which analysts believe is realistic (See: Undiluted success).

The Amul moppet can be fierce when it is on a warpath; the sweet, polka-dotted dress is deceptive. Ask Hindustan Unilever. In 2017, the butterly-brand picked a fight with the latter by calling HUL’s ice-cream a “frozen dessert”. It sounded snarky (even a sweetened cube of ice can be a “frozen dessert”). But, it was also effective messaging, that only Amul ice-creams were made of milk, the rest were made from vegetable fat. “Consumers didn’t know this. Our idea was to inform the consumers, so that they can make the best choice,” says Nitin Karkare, CEO of FCB Ulka Advertising, who worked on the campaign. It set off a war of words between the two brands, HUL filed a case against Amul and the matter is now sub judice.

This is not the first Amul-HUL face-off. In the early 1990s, HUL had acquired Kwality Wall’s, when only small-scale businesses were allowed to enter the ice-cream sector. But the British-Dutch conglomerate utilised an exemption, by purchasing an existing factory. The senior management at Amul was watching this development closely and wondered, if a “soap maker” can make a success of it, why can’t India’s biggest milk brand do it. They ventured forth and, today, Amul is the market leader in this segment with 14% market share and Kwality Wall’s has about 8%. Done and dusted.

Next, the moppet has set her eyes on the Rs.350-billion biscuit category. There are biggies already here — Britannia’s market share is about 34%, Parle’s 29% and ITC’s about 18% — and there seems to be another ‘frozen dessert situation’. Sodhi says, companies selling ‘butter cookies’ are misrepresenting the product. The butter content in their cookies is abysmally low at 0.3-3%, and they substitute it with 20-22% vegetable oil, which is a cheaper ingredient. “A lot of these butter cookies manufacturers used to buy butter from us. Then we saw that as the sales of some brands are increasing, their butter purchase is reducing tremendously,” he says.

The brand has launched its own line now of butter, chocolate and honey cookies this year. They have 25% butter and no vegetable oil. They are priced higher, at Rs.10 per 40 gm pack which is double of what its nearest competitor Britannia charges — Rs.5 for a 39-gm pack. Both Britannia and Amul are now premium players, and this is the market that is growing, according to Sanjay Manyal, analyst, ICICI Securities. “The market has shifted towards premiumisation and now the mass category constitutes less than 30% of the organised biscuits segment,” he says. Also cookies are a good extension for its butter business. “If we sell about 1,000 tonne in a month, then with 25% butter, we generate sales of 250 tonne of butter,” says Sodhi. It has since launched bakery products, such as nankhatai, that use butter only.

In July 2019, the brand pulled out its arsenal and launched the “butter war” on Twitter. Amul openly criticised other biscuit brands by stating their dismal butter content. Soon, thousands of users began sharing pictures of their biscuit packs, confirming the brand’s accusation. “This is a great strategy by Amul to own all categories associated with the word butter,” says Kapur. But Ravi Wazir, business consultant for the hospitality and food retail industry, believes all the wrangling is a waste of time.

“To create demand and to influence purchase of a brand, perception is often more important than the reality of what’s on their ingredient list. So rather than spending time in court, it would be far more effective if they simply got their butter brand mascot — the Amul girl — to endorse their butter cookies,” says Wazir.

Just as cookies and baked sweets help Amul increase its butter sales, its Tru fruit juices are a smart extension. The production of paneer and cheese results in creation of whey as a by-product. “People don’t like how whey tastes, so we thought of ways to make it more palatable. We saw that the juice category was growing, so we combined the two,” says Sodhi, adding that their Tru juice range is thus thicker than conventional refreshment drinks and has more protein. Another extension the brand has done is with frozen foods. For their ice-cream sales, they have a strong, pan-India distribution network. It works well during summer. But in winter, sales drop, and the refrigeration infrastructure lies unused. To better utilise it, Amul ventured into frozen foods (though, so far, these have only been met with chilly market reception).

‘Dark’ wars

In Amul’s diversification spree, perhaps the biggest surprise has been its meteoric rise in the chocolate segment. Though the brand has had a presence in the chocolate category, with 18 gm and 40 gm chocolate packs since 1973, nobody really cared about its bars. “We were struggling in this category for many years,” says Sodhi. In 2016, they executed a major revamp.

It launched big, 150 gm packs of dark chocolate variants, sourcing cocoa from Tanzania, Venezuela, Peru, Madagascar, Ivory Coast, Ecuador and Columbia. That was a big bet, the large bars priced at Rs.100-150, but Sodhi says “humko pata tha humara product bilkul badiya hai”. Within three years, its chocolate vertical has seen a sharp spike in sales, with 63% volume growth in FY19.

That said, its market share in the Rs.150-billion chocolate confectionary segment is still negligible at 3%. Mondelēz controls close to 58%, followed by Nestlé with 19%. The revenue generated by Amul’s chocolates is Rs.1.5 billion, which is meager compared to the brand’s total sales. But Sodhi is confident that both numbers will improve in two to three years — to 6% in market share and Rs.10 billion in revenue.

The company has invested Rs.3 billion to upgrade its chocolate facility at Mogar, increasing its capacity from 200 tonne per month to over 1,000 tonne. The 4,400 sq metre plant now manufactures not just the 150 gm dark chocolates, but also smaller packs and newer ranges like fruit-based variants, chocolate-coated almonds and chocolate spread.

In India, where Cadbury is used synonymously with chocolate, this is a big bet to place. However, the food head of a national supermarket chain says that Amul has made an impression on customers already. “For more than 25 years, Amul was not even considered a player in the chocolate market. But within such a short time, they are being considered a serious competitor… We have seen good traction for the product in all our stores,” he adds. He hastens to add that Amul is not eating into the share of other players. Instead, it is creating a new market by positioning chocolates as something more than just indulgence. Its premium dark chocolates are for the health conscious, and not just for kids.

Vernika Awal, a food blogger who writes for Delectable Reveries, says, the Indian audience has taken to dark chocolate very quickly in the past decade or so. “A lot has to do with the extensive research that puts forward dark chocolate as good for health and says everyone can have a piece a day,” she says. The nostalgia still works in favour of brands such as Dairy Milk though, she adds.

Anjali Mohan, a renowned pastry chef who runs Danbro café, is skeptical about the Indian palette taking to dark chocolate that easily. “What really works is the sweet chocolate with a creamy texture,” she says, adding Amul’s chocolates lack the creamy texture Belgian chocolates have. That said, dark chocolates are easier to distribute through the local retail supply chain. Amol Powale, who operates a 300 sq ft Amul store in Thane’s Hiranandani Estate, says, “These chocolates do not need refrigeration and so it allows retailers to stock more inventory and for longer.”

With the retailers, a food industry veteran says, Amul has another advantage over competitors — its sheer size. It generated Rs.330 billion in sales in FY19, when Mondelēz India did only Rs.61.2 billion (in FY18) and Nestlé India’s revenue is around Rs.113 billion. Amul can get to double-digit market share within three years, he says.

Sodhi believes chocolates have made the brand young again. Milk and dahi are sensible, but chocolates (however bitter and pumped with anti-oxidants) can never be that. “Before launching chocolates, Amul was an old, conservative and reliable brand. But with this revamp, it’s almost as if we are 18 again,” he says.

The brand has rarely been stodgy. In fact, it innovates with great spontaneity. A claim few other companies in this business can make. For example, Sodhi recalls how Amul Butter Spread with garlic and herbs came about. Once his daughter was applying butter on bread and followed it up with crushed garlic and oregano. That’s when he got an idea to try out butter with the same seasoning. This was meant to appeal to millennials who love ‘garlic bread’. This attitude of quick adoption of ideas has helped Amul produce and distribute products fast.

Sodhi says that once they identify a category to enter, they ask about two to three factories to try manufacturing it. After a little back and forth, they standardise the recipe and commission it for mass production. “We don’t make products in an R&D lab. We make it in the factories,” he says. The ideas themselves come from customer interaction (like with his daughter) or basic market observation. Thus, conception to launch takes just about three months.

Reaching out

While innovation is what is helping Amul keep pace and even get ahead of its peers, there are other wheels that are turning. For one, it has done its branding enviably well. Rahul daCunha, owner and creative head of daCunha Communications, says, “We live in an uncertain world, be it politically, economically and socially. In the midst of all this, Amul stands for stability.” His agency has been running the tongue-in-cheek Amul Topical campaign for the past 53 years. All the campaigns and products are also lined up behind the masterbrand, which builds the brand equity, says Karkare.

Second, it has worked out a great business model. This cooperative, which works with over 3.6 million milk farmers and procures around 23 million litres per day, runs on low margins. It buys at a higher price from the farmers, paying them 15% more than others, and sells at a lower price to the consumer. Retailers get margin of 3-8%, yet they are forced to stock it because consumers ask for it. Sodhi says, “We give them the volume… Also, we work on the ‘pull’ strategy, not the ‘push’.” Amul doesn’t need to push dealers to stock their products as there’s customer pull for it.

The earlier quoted retail chain’s head agrees that the brand has done well. “Amul is the best seller in categories it operates in. It doesn’t give much margin, but the prices of its products are low and consumers have such faith in the brand that you end up getting volume. So Amul plays the role of volume driver,” he says. While most companies operate at gross margin of about 30%, the brand is content with a below 20% gross margin. Which is why, Manyal says, if Amul decides to go full throttle in any category, then it could pose a threat even for the established players.

While retailers can’t do without Amul, Sodhi has already readied an alternative retail network for the brand. “We started our own retail touch points through a franchise network, around the year 2000, when government allowed 100% FDI in modern trade,” says Sodhi. This was done when the company feared that the international retailers might try to demand more margin to stock Amul’s products. The brand now owns 8,000 franchise outlets across India, located inside malls, high-streets as well as residential areas. Powale says that he has about 80 customers every day, and generates sales of about Rs.20,000 per day.

It may seem like the Amul girl can do no wrong, but there have been a few misses along the way. For instance, take the mithai business. Though Amul launched gulab jamun as early as the 1990s, Sodhi says that the first big success they saw was about three years ago, with the launch of rasmalai. This is because while the market is huge — about Rs.70-80 billion — it is largely unorganised. Also, vendors complain about Amul’s unreliable supply. Sodhi admits that they were conservative about the production of this line so far, but now they are ramping it up and working towards a 45-day shelf life. The latter to ensure consumers only get fresh goods.

Another vertical in which the company has seen limited success in is frozen products, about a Rs.10 billion category. Launched in 2017, the ‘Happy Treats’ range includes frozen pizza, dahi tikki, cheese poppons and other potato based snacks. Analysts are skeptical about the prospects of Tru juices too. Its 200 ml pack, in four variants, is priced at Rs.10. But this Rs.11-billion segment already has strong players such as Frooti, Maaza and Minute Maid. Sodhi is unperturbed. Analysts say rightly so, since these are small investments for a company its size, with capital efficiency and a dependable distribution network.

Amul turned 73 this year. It does not act its age and never has. It has always been that clever kid on the backbench, who throws a paperball at everything — the forced sterilisation drive, rumour-mongering that causes violence and even an economic slowdown in early 1980s. If impishness, with its courage to push boundaries, is a strategy, then the company has aced it.