The landscape of India’s Garden City, Bengaluru, changes when you enter Electronic City. If you see it in the right hour — the greenery is manicured, buildings are towering and shimmering, and the roads stretch to a farther horizon. In the midst of all that opulence, it is still hard to miss a sprawling new addition — the Lenskart store.

In the ground floor of a two-storey building, the 5,000-sq ft store houses eight merchandising zones and many facilities. What could a spectacles store have, besides the right-sized mirror and a wipe? Ask Lenskart. Its store has an eye-massage lounge, a juice bar and a makeover salon, and then there is impressive tech such as virtual machines for a 3D try-on. It is exactly what its co-founders, Peyush Bansal and Amit Chaudhary, envisioned for the brand.

“When somebody is operating offline and online, technology plays a big role. For example, when you go to a Lenskart store, you will ‘browse’ a store, like you do online, without interference. It is built as a seamless experience,” says Chaudhary, who co-founded Lenskart as an online portal to sell eyewear, in 2010. Inaugurated in May, this is the 500th and the largest store for Lenskart.

The company stepped into the offline world in 2015, when it had about 1.5 million customers. It has since added an average of 13 stores a month. Today, it has a customer base of seven million and offline transactions contribute as much as 75% of its overall business. Little wonder then that brick-and-mortar stores are the preferred channel for trade in India (See: Touch and buy).

Chaudhary states that their target is to achieve 50% market share in the Indian eyewear market. That cannot be achieved only with an online presence. Therefore, their plan is to hit 1,000 stores across the country in the next two years with major focus in the South. The overall eyewear industry is highly unorganised, and Lenskart reportedly has 10-15% of the market.

The eyewear company, looking to expand at a faster pace, is speeding through the franchise route. Almost 40% of their stores are franchises. “We franchise when there is need for local help, for example, in Tier-III cities,” says Chaudhary. Lenskart provides the products, marketing and advertising while the franchisee invests in opening the store.

Interestingly, this isn’t the only e-retailer seeing merit in an offline set-up. For instance, Nykaa, an online cosmetic and personal care player, ventured out with two stores, one each at Mumbai and Delhi airport in 2015. “It was done purely for marketing and visibility,” says Anchit Nayar, CEO-retail, Nykaa. But they quickly realised that these stores could mean more.

Beauty products are bought after trials and experiments. Remember picking that metallic blue lipstick in the store, trying it out, and then settling for a sober nude? Other people aren’t very different. “We found that 70% of our customers are truly omnichannel. They like to shop in-store and then replenish online,” adds Nayar. The company thus kicked off its offline foray in earnest in 2017, and has since scaled to 38 stores across India. They plan to open 180 stores by 2023.

Nykaa has two retail formats — Nykaa Luxe and Nykaa On Trend. The first is 1,500-3,000 sq ft and stocks luxury beauty brands, and the second could be as small as 600 sq ft, stocking 2,000 stock keeping units (SKUs). These formats require a capex of about Rs.5 million to Rs.8 million, depending on the store size and location. “Nykaa’s break-even period at store Ebitda level is six months,” says Nayar. They have been credited for bringing traffic — of young women with disposable income — into malls as opposed to other retailers who are present in a mall to benefit from its footfall.

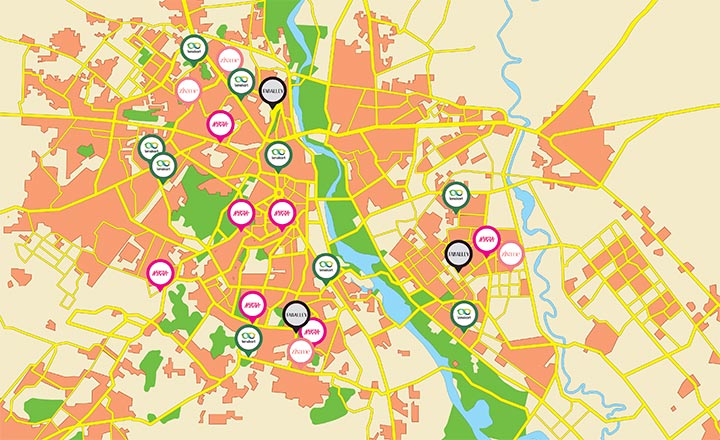

This trend manifests across e-commerce sectors. For instance, furniture and home-décor company, Pepperfry, built its first offline store in 2014. It has 42 of them in 20 cities today. Similarly, lingerie market leader Zivame, premium tea brand Teabox and fashion apparel brands such as Myntra and FabAlley, have begun viewing offline retail as a serious business opportunity. It is now more than just a branding exercise.

Evidently, the trend of online-to-offline that started a few years ago is gaining pace in India. “The co-existence is a given now,” says Prerna Bhutani, partner at India Quotient, a firm that funds start-ups. However, she adds that both channels target different sets of buyers. “A lot of these brands have collections and price points different from what they are online,” says Bhutani. While Lenskart and Zivame keep their prices same on the two channels, online stores generally have more discounts and deals.

Allure of bricks

E-commerce players see a good reason to come to the streets —there are far more buyers. There are about 60 million people transacting online in India. If we exclude mobile phones and consumer electronic purchases, this number comes down to just 30 million. “Online customer base is still small and most people still want to touch and feel the product before buying. All brands are waking up to this reality. They realise that online-only brands will remain subscale, that you have to go offline to expand,” says Mukul Arora, managing director, SAIF Partners.

According to a Deloitte report released in 2019, overall retail is likely to expand from $795 billion in 2017 to $1,200 billion by 2021. Within this, organised retail and e-commerce constitute 9% and 3%, respectively. By FY21, these are expected to constitute 18% and 7%. Today, e-commerce has just about 5% of the total retail market in India, points out Anil Talreja, partner, Deloitte India, adding that there is definitely room for deeper penetration.

In niche categories, the penetration is even more nascent. Zivame’s CEO, Amisha Jain, states that in the lingerie category, online makes up just 2% of the business. “More than 85% women don’t know their right bra size. We wanted to go from online to multichannel and make the brand more accessible,” she says.

Zivame, which has more than 30 stores across 10 cities, is now exploring the franchise route to achieve its target of doubling the store count in a year. It is also present offline through nearly 800 multi-brand outlets. Online still constitutes about 80% of its revenue, but Jain says, “Both retail and online channel will grow simultaneously for the next couple of years. We will be firing on all cylinders.”

Besides a larger buyer pool, there are other pluses to going offline. For one, there is more money to be made. Shivani Poddar, co-founder of FabAlley, says that while offline is more capital heavy, it is also profitable as a channel. “You make a lot more money quicker and turn operationally profitable early on in offline. Which is why, from business sustainability point of view, offline works well,” says Poddar, who co-founded the fashion apparel portal with Tanvi Malik in 2012.

Window shoppers are more likely to buy and shoppers are likely to spend more at a regular shop; online, 78% of the visitors abandon their carts (See: Browser hopping). At FabAlley, the customer conversion rate is 10% in stores and about 2% online, while Lenskart states that their conversion rate offline versus online are 30% and 5% respectively. The average bill value in-store is 1.8x higher than online for most e-commerce players.

A brick-and-mortar outlet also helps change perception. People log on to shopping sites looking for a discount. Honestly, no one opens that page to gaze at its harmonious colour palette or perfect typography. Therefore, as soon as an e-store stops discounting or goes beyond a ticket size, growth stutters. “If you want to grow faster than the market, you have to go offline, which will likely remain a much bigger market for brands,” says Bhutani.

India is still a ‘touch, taste and feel’ market, says Kausshal Dugarr, who founded Teabox in 2012 as an online platform. His brand sells tea to over 100 countries around the world. “Once Indians make the first purchase offline, it is easy for us to convert them to an online buyer,” he says. In 2018, they opened their first retail store at the Mumbai airport. Their store has a multi-sensorial area where a customer can touch, feel, smell and taste about ten kinds of tea. It must have worked because now they plan to open a store at Bengaluru airport, which will be followed by a store in Mumbai and Bengaluru city.

But isn’t a store on the web cheaper than one in a busy neighbourhood? Not really. Both don’t come cheap. In both, the gross margins remain at about 35%. One spends on customer acquisition and the other on rent and salaries. Anurag Mathur, partner and retail expert at PwC India, says, “Customer acquisition plus logistics is more expensive than rental and operations cost.” According to industry estimates, in an offline format, rentals constitute between 8% and 14% of total expenditure and store operations, another 8%. However, online customer acquisition cost can go as high as 35%.

While these offline advantages stand, no one is packing up their wires and websites and heading out. The e-store founders believe an online presence is as important for a company as offline. For one, there is the brand recall built from all the digital marketing done over the years.

Nayar says that when opening a new store, they do not have to buy 20 billboards across the city to announce their opening. “We can just publish one social media post and send an app notification to all our customers,” says Nayar. Mathur of PwC says that, to outshout other people and get customers to your site is tough online, but once a brand has done that, it becomes easier in the physical retail space.

Easy transition

Going online first has helped many companies grow fast and become quickly popular. Nayar says, “It took us just six years to build a household brand name like Nykaa (founded in 2012) with 50 million monthly visits. To reach that kind of scale is very difficult for an offline retailer.” He adds that the plan was to be an omnichannel retailer since the beginning.

Poddar’s FabAlley, an affordable fast-fashion brand, opened for business the same year as Nykaa. In two and a half years, they had 100,000 customers and raised Rs.1 billion from private equity firm TPG Growth.

“It would have taken longer for a new offline brand (due to limited reach geographically),” she says. The start-up sold apparel designed in-house on their website, as well as, on Myntra and Amazon. FabAlley achieved a turnover of Rs.500 million by 2016 from online sales. This has jumped to Rs.800 million in FY18 and Rs.1.4 billion in FY19.

Besides the brand recall, e-commerce stores won over buyers with steep discounts and investors queued up for multiple rounds of funding. Gradually, revenue rose and losses contracted for a few who could generate customer stickiness and pricing power.

Lenskart’s revenue rose by 70% in 2018 to Rs.3.11 billion (expected to have crossed Rs.5 billion in FY19) and losses dropped by 55% to Rs.1.18 billion. Similarly, Nykaa expanded net revenue to Rs.5.70 billion at the end of March 2018, against Rs.2.14 billion in 2017. Loss in the same period contracted to Rs.280 million from Rs.360 million. FabAlley, too, has turned operationally profitable. Meanwhile, Zivame posted Rs.866 million in revenue in FY18, about 63% increase from the previous fiscal year. Its loss declined by 44% to Rs.321 million.

Strategic strides

These companies are certainly benefitting from adapting their businesses to suit both channels, but they steadfastly remain technology-driven. This positioning gives them an edge, particularly in understanding and responding to customer behaviour.

Prashanth Prakash, partner at Accel, believes that a company can use its online experience to improve its customer’s offline shopping. He gives the example of Teabox, in which Accel has invested. They used their technology to choose ‘what to launch’ and ‘where to open stores’; Teabox has seen 4x growth in the past five months.

“Plus, they need to remember that their store should not look similar to any other traditional offline store. When a customer comes, he should know this is a new-age brand,” adds Arora.

The e-commerce firms are cognizant of this requirement, and Teabox has successfully accomplished this feat. “We introduced a lifestyle setting in the store through elements such as a study and yoga space, to showcase instances where our tea can be your company,” says Dugarr.

Meanwhile, Nykaa observed from their customer data that their product has a demand not just across Tier-I, but also Tier-II towns and cities. “We know that 50% of Nykaa’s online customers are actually from outside the top seven metros. Hence, we started building stores in non-metro cities, namely, Amritsar and Coimbatore before anyone else,” shares Nayar. While choosing the location, Nykaa ensures that they never venture out of the ground floor of a mall and all the stores have experiential components such as make-up counters and a trained make-up artist to guide the customer.

Starting afresh

Online-first companies seem to be making a relatively easy transition offline but they have their blind spots. One of the biggest concerns, according to Arora of SAIF Partners is the aggression in their expansion strategy. “When operating online, these companies have a very aggressive DNA where they believe they can grow 15-20% month-on-month. Offline doesn’t work like that. Selecting a property is hard. You have to pick the right real estate at the right rental; otherwise these properties will lose money. Ensure that every store becomes profitable within six to 12 months of opening,” he asserts.

Essentially, building offline has to be in a calibrated manner versus the hyperscale model online. So the investment has to be made wisely. Consider how start-ups such as Freecultr, Zovi and Yepme had made their offline foray between 2014 and 2016, but saw limited or no success. According to Entrackr, a website which exclusively reports on the Indian internet economy, even a well-entrenched online player such as Myntra hasn’t seen much success offline. It launched its private label brand Roadster in the offline channel in 2017 and had made robust expansion plans, which haven’t really materialised owing to high rentals and lower ticket sizes of products. Although Myntra is just one such example in India, of a big online name not seeing a favourable outcome offline, challenges still remain for any such venture.

Nayar acknowledges that when an online-first brand goes offline, it is a completely different business model. “We had to learn retail. And it isn’t easy. It is a competitive business and margins are razor-thin because of salaries and rents. But we leveraged brand relationships and have been fast learners,” says Nayar, adding that they open stores based on in-depth feasibility analysis.

Another concern is managing inventory. Poddar states that an online player has to manage inventory from a single warehouse or two. But when it goes offline, it needs to have multiple warehouses because all stores have mini-warehouses. FabAlley works on a lean supply chain to avoid piling up of inventory. Yet, their inventory days are way higher at 30 than what it was in their online-only days at 18.

Using data analytics to predict demand, deploying technology to create a dynamic shopping experience and leveraging their nimble-footed approach to business will continue to augur well for the fresh batch of retailers, as they go about ramping up their presence. Amazon and Alibaba, the global e-commerce giants, have already done this in their home markets. While Amazon impressed people with its curated bookstore format in 2015, Alibaba has delivered a masterstroke with its offline retail format — Hema — which completely digitises the value chain. From digitised aisles and farm-to-store food tracking to service robots and cashless check-outs, the store is truly a disruptor in offline retail.

By going offline, e-commerce companies are creating more integrated and technologically evolved places to shop. And though at a nascent stage, Indian e-commerce firms could well alter the offline shopping experience. After all, disruption has always been their favourite game.