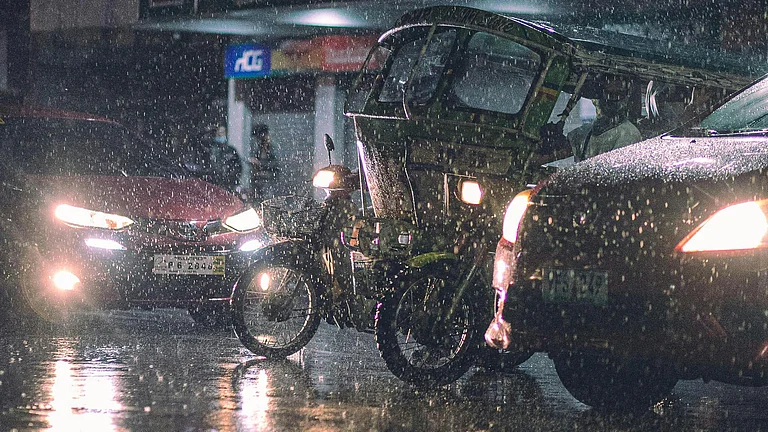

The Southwest Monsoon covered the whole country by June 29—nine days ahead of schedule on July 8— raising questions about changing climate patterns and its impact on India’s agriculture economy. This is only the tenth time since 1960 that monsoon has arrived early and covered the entire nation by June-end.

The seasonal monsoon is the lifeblood of India’s $4 trillion economy, supplying almost 70% of the rainfall needed to water farms and replenish aquifers and reservoirs, according to a 2023 ScienceDirect study.

What Drives Early or Delayed Monsoon?

The early onset of monsoon across the nation is attributed to several factors, including the active phase of Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) — an eastward-moving system of wind, clouds, rainfall and pressure that originated in the Indian Ocean. It brings increased cloud cover over Southern India, which is then carried northwards by monsoon winds, leading to increased rainfall. May and June witnessed an active MJO phase.

Following the onset of monsoon, it advanced ahead of its schedule over the southern peninsula, to the east and northeast parts of India; it was near normal over the northwest region. However, it was slightly delayed in central India.

According to Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), other drivers of the early monsoon include an active MJO, multiple low-pressure systems and favourable monsoon trough, all of which helped it advance rapidly across India this season.

The southwest monsoon is further affected by El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). ENSO—a phenomenon defined by changes in sea temperatures along the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, accompanied by fluctuations in the atmosphere overhead—has three phase: El Nino, La Nina and neutral.

El Nino is responsible for suppressing monsoon while La Nina and neutral condition causes stronger and normal rainfall respectively. In June, Neutral ENSO conditions dominated, helping maintain stable rainfall, unlike El Nino, which suppresses monsoon activity across India.

Monsoon’s Effects on Agriculture

Nearly half of India’s farmlands depend on the annual June-September monsoon rains for irrigation and consequent crop growth.

The all-India average rainfall stood at 180 mm in June, which was quantitatively 9% above normal, according to IMD. This discontinued the trend of deficit rainfall being observed during June since 2022, according to The Indian Express.

Over 80% of the meteorological subdivisions of IMD recorded normal or above normal rainfall in June, according to the report, including key kharif sowing regions. Kharif crops, also known as monsoon or autumn crops, are cultivated and harvested during the monsoon season (typically between June and November).

The early onset of rains has helped farmers begin sowing earlier than usual, Farm Secretary Devesh Chaturvedi told Bloomberg. He added that if the rains continue at a normal pace till September, it could benefit both the current crops and the upcoming winter harvest.

Certain crops that require more water and irrigation even in areas of heavy rainfall, such as rice, sugarcane, jute and cotton—get directly influenced in terms of crop yield, farmers’ income and inflation. Above-average precipitation further helps support economic growth while stabilising global agricultural markets.

According to Chaturvedi, if the rains stay favourable through September this season, 2025 could mark a record year for Indian agriculture. An above-average rainfall in July for India, as predicted by IMD will shape conducive conditions for planting of key crops such as rice, soybeans and corn. Rains in India are expected to exceed 106% of the long-term average of about 28 centimeters, Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, director general of the Indian Meteorological Department, said at a briefing on June 30.

While the monsoon rains brought relief from sweltering heat, this sudden switch is not usual. What’s reason behind this anomaly?

A Sign of Climate Change

Two developments point to the erratic behaviour of the weather this year. The monsoon's early arrival by one to two weeks across various regions was the first indication, followed by its expansive coverage from Kerala to Maharashtra in a single day on May 24. According to a report published by the CEEW, climate change is warming the atmosphere and increasing its moisture holding capacity, causing increased frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall events.

However, early onset of rainfall in 2017, 2018, 2022 and 2024 did not take the shape of consistent rainfall patterns or outcomes. Erratic monsoon behaviour not just surfaces as a weather anomaly, it indicates serious implications for agriculture, water security and broader economy in the long run.