The pride in Akhil Gupta’s voice is palpable when he speaks about how much Bharti Airtel has achieved. And that is not without reason. From being an absolute novice in the telecom sector when it was opened up in the mid-1990s, the company today is India’s largest cellular operator with a subscriber base in excess of 188 million and revenues of Rs.71,500 crore.

Gupta, who has since progressed to become deputy group CEO and MD, Bharti Enterprises, has had no small role to play in this almost unbelievable journey. As he speaks of it passionately, he does not forget to mention the role played by a certain private equity major called Warburg Pincus.

“They encouraged us to think big and supported every expansion. They took early risks and that gave us confidence,” he says. What is not commonly known is that Bharti had never heard of Warburg till the two sides met for what the telecom company presumed was a “courtesy call”. Gupta recalls that interaction way back in 1999, which was set up by a banker acquaintance. “We were not so sure about the purpose of the meeting.

We met Pulak Prasad and soon realised they were quite serious about understanding our business. It was a meeting of minds,” he says with a slight chuckle. That meeting with Prasad, who had recently joined Warburg as an associate after six years at McKinsey & Co, was the catalyst for the PE firm’s decision to invest $290 million in Bharti — about $60 million in 1999 itself and the remaining in the following two years.

By the time Warburg Pincus exited its investment in Bharti in October 2005, the cellular company had grown from a presence in just six circles and under 300,000 subscribers to a pan-India player with 14.7 million subscribers. It had made significant buyouts in key circles like Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Chennai; the stock had listed on the bourses and Warburg sold its holding for $1.83 billion, making a profit of a little over $1.5 billion.

In the admittedly short history of private equity in India, this deal remains a landmark. And Warburg’s prescience in the Bharti deal led to expectations that it would have an equal degree of success in its other investments in India. Certainly, Warburg, which has invested $3 billion till date in India, has had some great successes — Ambuja Cements, Kotak Mahindra Bank and DB Corp among the prominent ones. But of late, the talk in PE circles is that Warburg seems to have lost its Midas touch.

Many investments aren’t doing well and some of the fund’s choices have been ill-timed, in companies that neither had a sound business plan nor were backed by promoters who had the zeal to create a long-term business. What’s gone wrong?

No encore

If the investment in Bharti was a multi-bagger, Warburg’s $220 million (Rs.1,018 crore) investment in Moser Baer turned out to be a lemon. As with Bharti, the investment was in tranches, with the first round of $62 million made as far back as 2000. At that time, Moser Baer, which had established itself as a floppy disk manufacturer, was looking to make its mark in the CD-R (compact disc-recordable) market. Before Warburg came in, International Finance Corporation (IFC) had already invested $25 million through a combination of debt and equity in the proposed $91 million project. The underlying assumption was that Moser Baer would become one of the world’s cheapest manufacturers of CD-R.

Everything seemed to be on track initially — Moser Baer quickly gained over 15% share of the global market and became among the largest CD-R companies in the world. In 2002 Warburg pumped in another $10 million and the company’s revenues shot up from Rs.770 crore that year to Rs.1,580 crore in 2004, while profits at the consolidated level went up from Rs.210 crore to Rs.330 crore. And then everything went haywire.

A glut after 2004 thanks to overcrowding in the CD-R market, took a toll and soon, profitability took a hit. Still, Warburg invested another $149 million in 2004 through a GDR issue, at Rs.336 a share. It defended the investment — its largest in India after Bharti — saying Moser Baer had a unique business model and good growth prospects. It couldn’t have been more wrong.

Following the CD-R failure, Moser Baer ventured into solar technology, but the business went cold during the 2008 crisis. From Rs.1,620 crore in 2005, the company’s debt soared to Rs.3,500 crore six years later and interest costs increased four-fold to Rs.300 crore. Revenue has remained almost flat at around Rs.2,800 crore and the stock currently has a market capitalisation of just Rs.120 crore.

This May, after being invested in Moser Baer for a dozen years, Warburg sold a 24.5% stake for just Rs.60 crore (less than $11 million). It still holds 9.05% in the company, whose stock is quoting at around Rs.7. Barely a week after the sale, Moser Baer announced a corporate debt restructuring program for half its debt and less than a month later, Rajesh Khanna, the former Warburg managing director who had driven the Moser Baer investment, resigned from the company’s board. Khanna and Moser Baer refused to comment on this story and Warburg Pincus’ team in Mumbai declined to participate.

If the Moser Baer debacle can be blamed on global developments, Vaibhav Gems was a case of a business model gone completely wrong. In December 2005, Warburg acquired a 27.2% stake in the company at about Rs.280 per share, for a total outgo of Rs.245 crore. The Jaipur-based company’s focus area at the time was studded jewellery aimed at international cruise travellers. It had lately spent Rs.400 crore buying the STS Group and expanding its operations in the US, Canada, Japan and Hong Kong; it had even started a 24-hour jewellery shopping television channel in the UK, the US and Germany. “We positioned ourselves as a luxury offering. It was a mistake,” concedes Atul Agarwal, vice-president and group CFO, Vaibhav Gems.

The slowdown and its aftermath took a heavy toll, and Vaibhav’s sales declined from Rs.665 crore in FY07 to Rs.295 crore in FY10; consolidated losses over the period stood at Rs.586 crore. The company has undertaken various measures, including shutting loss-making businesses in Thailand and Japan, switching its positioning from luxury to lifestyle and lowering prices.

But, as Agarwal points out, “the stock market is finding it difficult to understand the business model”. As it turns out, Warburg, too, gave up. In March 2011, it sold its entire holding, taking a 92% haircut — the Rs.245 crore investment fetched barely Rs.18 crore. Incidentally, another marquee investor has stayed put: in 2007, former Warburg MD Pulak Prasad’s Nalanda Capital had invested Rs.94 crore in Vaibhav Gems at Rs.230 per share.

Wake-up call

It’s not easy to explain why PE funds back promoters with unimpressive track records or unclear business models. The results of such investments, though, are out there for all too see — insipid or even a negative return. But in the case of Warburg, it seems to be a case of being behind the times and sticking to a set formula. A private equity veteran who prefers anonymity says, “The world has changed after the Bharti deal and there has certainly been a time lag at Warburg in recognising that. A clear mistake was to repeat the Bharti model, which was investing money in a company and leaving the running of the company to the entrepreneur. This ‘freedom’ was often a bad idea and resulted in many bad investments.”

At the same time, increasing competition among PE firms also led to too much money chasing too few companies. Seasoned investment banker Rajeev Gupta points out that India attracted the interest of every global PE fund in the past decade. “The learning for most, from this investing honeymoon was that, the number of companies having the governance culture and integrity of financial statements to be eligible for PE investments, is only a fraction of the Indian universe,” he says. The result: valuations that defy logic.

That is why Warburg’s decision to stay away from PIPE (private investment in public equity) deals during market lows is hard to understand. The firm’s long tenure in India means it has seen several business cycles here — the dotcom burst of 2000, the lows of 2003 and 2008 among others. These were times when several interesting picks were available at a very attractive valuation but Warburg continued with its focus of buying a negotiated stake from the promoter. “It seemed like they were a little edgy about India and missed some serious opportunities when the markets fell,” says a senior executive at a rival PE fund with exposure to energy and financial services.

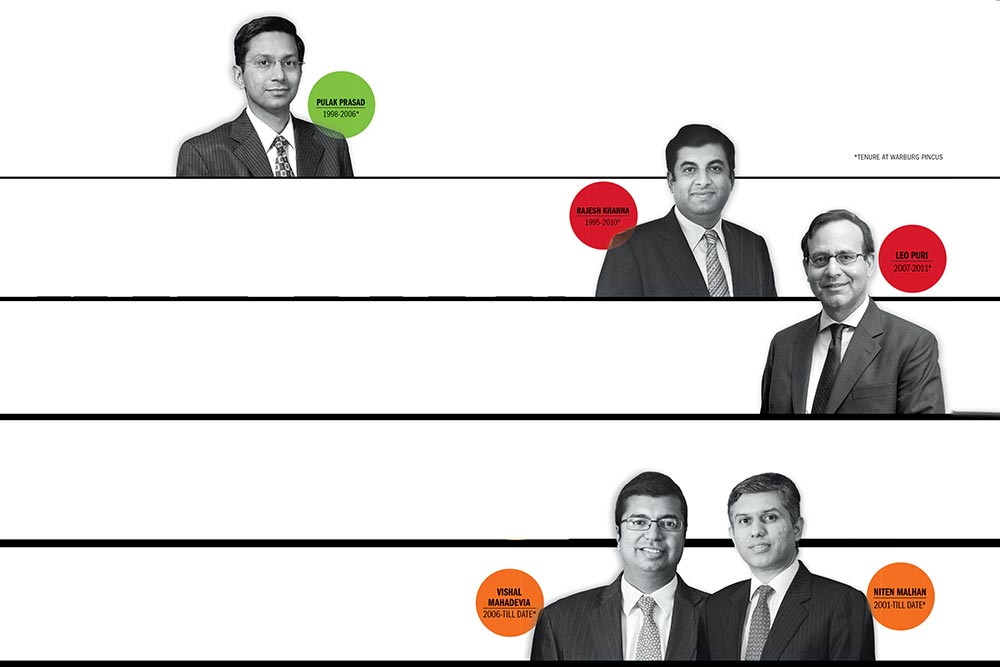

There is also the belief that Prasad’s exit from Warburg in late 2006 was a significant development. He had driven several key transactions like Bharti, WNS and Rediff. Prasad’s successor was McKinsey & Co’s Leo Puri. He was at the helm from 2007 till 2011 and it was during this time that Warburg invested in Punj Lloyd, Amtek Auto and Havells India — mostly during the 2007 peak — apart from investing in non-PIPE deals such as Gangavaram Port and Laqshya Media. Many of those chickens have now come home to roost.

Take Punj Lloyd for instance. In August 2007, Warburg acquired 5.5% of the company through a qualified institutional placement (QIP) at Rs.275 per share. Markets were climbing and in January 2008 the stock peaked at Rs.578. Other investors who participated in the Rs.814 crore QIP included Avenue Capital, Moore Capital and Blackstone.

Punj Lloyd’s troubles began with the fact that the infrastructure sector never regained the high that it saw in 2007 and 2008. It didn’t help that the 2006 acquisition of SembCorp Engineers & Contractors came with an albatross round its neck — loss-making British subsidiary Simon Carves. (It wasn’t until July 2011 that the company finally decided to withdraw additional financial support to Simon Carves)

The result: from Rs.1,700 crore in FY07, debt climbed to Rs.4,500 crore in FY11 while revenue growth was nearly flat, from Rs.7,950 crore in FY08 to Rs.8,200 in FY11. If that was not bad enough, the crisis in Libya took its own toll — the company had an order book of Rs.4,000 crore from the North African country but had to stop all work there due to political turmoil. Activity on infrastructure and oil and gas projects is expected to resume only in the next three to six months. While the company has a total order book of over Rs.27,000 crore, investors don’t seem too convinced. The Punj Lloyd stock currently quotes at Rs.50, which means Warburg is down over 80% on its original investment.

It also seems that Warburg is hoping high from its stake in Havells. In October 2007, the PE firm acquired an 11.2% stake in the electrical and power distribution company in a $110 million equity and warrants deal; Warburg bought equity at Rs.625 a share. By February 2009, the Havells stock was quoting at Rs.115, thanks to its debt-funded $300-million acquisition of Sylvania and its subsequent losses due to the slowdown.

Still, Warburg converted the warrants at Rs.690 apiece, that is, six times the prevailing price. “While the going was not easy for us and the stock was down, Warburg did the responsible thing by converting the warrants at the agreed-upon price,” defends Anil Gupta, joint managing director of Havells India. In the past couple of years, the company has managed a turnaround of Sylvania and is confident of growing sales at least 10% over the next three or four years, he adds.

Other PE funds have perhaps been smarter. SAIF Partners, a growth capital PE fund with a focus on Asia, chose to invest in Havells in late 2008 and early 2009 at a price as low as Rs.160 per share. In May this year, it exited the company, making a 3X return on its investment. During the same period, Warburg picked up an additional 3% in Havells — at an estimated Rs.240-380 per share — through the open market to average out its acquisition price.

Warburg’s investment in Amtek India also sputtered. In 2006, it picked up a 9.49% stake in the auto component firm for around Rs.200 crore (Rs.200 per share). The PE firm’s holding fell to 7.45% after an equity recast. While Warburg was clearly banking on the boom in the global automobile market to have a positive impact on Amtek’s fortune, the slowdown brought all those plans to a screeching halt. From Rs.1,360 crore in FY08, turnover fell to Rs.870 crore the following year.

Worse, profits over the same period dropped 84%, from Rs.353 crore to Rs.58 crore. After staying invested for four years, in November 2010 Warburg sold a little over 4% of its holding for barely Rs.35 crore (Rs.64.96 per share) and registered a loss of over 60% on the transaction. Fellow PE fund ChrysCapital was more successful in cutting its losses: it acquired a 8% stake in Q2FY09 at around Rs.80 a share and exited in November 2010 at Rs.64.5 a share, losing 20% of its original investment. Amtek did not respond to queries from Outlook Business.

Future play

In December 2011, Warburg made an important announcement: the appointment of Niten Malhan and Vishal Mahadevia as co-heads of the firm’s business in India. Malhan has been with Warburg for over a decade, while Mahadevia has spent around six years. Six months later, the duo created a stir when they announced their first major deal — a 53.67% stake in Future Capital Holdings (FCH), a Pantaloon Retail subsidiary.

The FCH stock has been pounded since the company went public in 2008: from an offer price of Rs.765, it trades at about Rs.150 today. As part of the deal, Warburg picked up FCH stock at Rs.162 per share for a deal size of Rs.560 crore and will infuse another Rs.100 crore through a preferential allotment.

According to Future Group CEO Kishore Biyani, what drew him to Warburg was the fact that the PE major had invested in a large number of “interesting” industries, including financial services: in March 2012, Warburg invested $50 million in Jaipur-based non-banking financial company (NBFC) AU Financiers. “I was impressed by their transparency and long-term vision for our business,” says Biyani.

He agrees openly that FCH was going through a tough patch. Debt at the group level was about Rs.5,000 crore and he had been looking to divest FCH for quite some time. FCH has already reinvented its business model considerably in the years since its inception: from wanting to be in investment advisory, financial retail and research, it is now an NBFC that caters to small and medium enterprises and secured retail lending. “Things were very different in 2008. It was important that our business model evolved over time and I think we have managed to do that,” Biyani says. The deal with Warburg is said to be a way to exit non-core businesses for Pantaloon Retail and strengthen its own balance sheet.

But what does Warburg get out of the deal? “Warburg saw long-term potential in FCH and they believed it was the right time to invest,” declares Biyani. Given the poor performance of the FCH stock, it’s logical to assume there must have been some pressure on valuation. Biyani deftly avoids a direct answer, merely saying, “If you like someone, things do work out.” Meanwhile, from Warburg’s point of view, there are still issues to be resolved, such as the go-ahead for the mandatory open offer, which is stuck in regulation. How the PE fund, which could end up with a 70% stake if the open offer goes through, will make the most of this buyout is still unclear.

A mixed bag

Indeed, most investee companies acknowledge Warburg’s contribution to their own growth story. Bharti’s Gupta points out that the Warburg emphasis on expansion is contrary to the norm. “Most PE funds don’t like it when their investee companies decide to expand. They think it increases the gestation period and increases costs over time,” he says. Prasad and his team, in contrast, egged Bharti to go pan-India when its ambitions centered on North India.

Others echo that thought. Consider the Max Group, where Warburg invested in Max India and Max Healthcare. The firm invested in Max India in May 2004 by acquiring 29% through a preferential issue for Rs.200 crore. This was followed up by an investment of Rs.25 crore in January the following year in Max Healthcare and another infusion of Rs.115 crore in June that year.

According to Mohit Talwar, deputy managing director, Max India, Warburg came in a critical time when the group was looking to invest in long-gestation businesses like life insurance and hospitals. “What helped us was the domain expertise they brought into both these businesses from their international experience, in addition to being a sounding board,” he explains. The firm encouraged the group to look beyond the National Capital Region and consider places like Mohali and Bathinda, he adds. “They remained very supportive of whatever expansion we had in mind.”

That said, Warburg’s returns in the Max companies can be best described as a mixed bag. It began diluting its holding in Max India in 2009 and had managed a return of at least 3X by the time it finally exited in April this year. But the Max Healthcare case is perplexing. After investing Rs.140 crore in 2005, it sold its 16.37% stake to Max India in June 2011 when the market cap was Rs.855 crore. It’s not clear why Warburg chose to do so because two months later, Max Healthcare sold a 26% stake to South Africa’s Life Healthcare for Rs.516 crore — which valued it at Rs.1,985 crore.

Infra bitten

Warburg is no different from other PE players in its fancy for the infrastructure sector. “PE firms are attracted by huge pent-up demand and successful execution invariably creates value,” points out Jayanta Banerjee, managing partner at ASK Pravi Capital Advisors. In power, Warburg has invested $150 million in the Bhaskar Group-backed Diliigent Power.

Incidentally, Warburg had invested Rs.150 crore in DB Corp in 2006, and made a 1.8X return after divesting a part of its holding when the company went public in 2009, and the rest in August 2011. Diliigent, which received funding from Warburg in May last year, said at that stage that it was in the process of setting up power projects aggregating 6,400 MW.

The company did not respond to Outlook Business’s detailed questionnaire; managing director Girish Agarwaal merely said the fund infusion from Warburg was an extension of the association with the PE major after DB Corp. “Warburg’s investment is an endorsement of the high level of governance apart from our strong execution capabilities,” he added.

Another infrastructure foray for Warburg has been Gangavaram Port in Andhra Pradesh, where the firm picked up a 31.5% stake for $35 million in September 2008. With a 21-m water depth, the port is among the deepest and most modern in India and is currently expanding cargo handling capacity to over 45 million metric tonnes. “The advantage is that Warburg has a long-term outlook,” points out Pranav Choudhary, CFO, Gangavaram Port.

Importantly, Warburg’s investment in Gangavaram was the last before a near two-year hiatus. The next deal came only in June 2010, when it picked up a minority stake in Metropolis Healthcare. This was after ICICI Venture exited its Rs.35 crore investment in the company after making a return of 5X. Warburg’s $85 million investment included a $10 million credit line for acquisitions.

Metropolis, which has a chain of 100 diagnostic laboratories across India, Sri Lanka, South Africa and West Asia, is now looking for a significant foothold in Africa. Says managing director & CEO Ameera Shah, “In terms of pathology, Africa today is where India was 10 years ago. We are looking closely at an acquisition in East Africa and also in Western and Central Africa.”

In April 2011, Warburg ventured into the logistics space, investing $100 million in Chennai-based Continental Warehousing Corporation, a subsidiary of the NDR Group, which has 6.5 million square feet of storage space across 70 locations in India. “This is a sector that is a derived demand beneficiary. It has significant entry barriers and Continental is a leading integrated player across CFS (container freight stations), ICD (inland container depot) and warehousing segments,” says Y Rama Rao, managing director, Spark Capital, the investment banker for the transaction. The valuation for this deal was done by comparing Continental to peers like Gateway Distriparks and Allcargo. According to Rao, the interest from PE funds in the logistics space (Blackstone has invested in Allcargo and Gateway Rail) comes from the fact that this is one of the few businesses that is capital-starved and a scope to earn a high return on equity. “Continental Warehousing should be listed in three to five years,” he adds.

Back to business

In any case, return on investments like Gangavaram and Metropolis will be calculated when Warburg has entirely exited. That is why Warburg’s Rs.280 crore investment in Lemon Tree Hotels in 2006 bears a second look. According to CMD Patu Keswani, the company plans to list in FY15. “We will go public after we become the second-largest owner of hotel rooms in India with over 3,500 operational rooms,” he says. Currently, Lemon Tree has close to 2,000 rooms and expects to close FY13 with an operating profit of Rs.100 crore on a Rs.250 crore turnover.

“By FY16, we will have revenues of over Rs.700 crore and an operating profit of close to Rs.350 crore,” Keswani declares. But Warburg’s association with Lemon Tree may continue even after a listing. Media reports say the two are considering a joint venture for a Rs.1,400-crore affordable housing project in Gurgaon. Keswani doesn’t deny the reports but says it’s too preliminary to talk about.

The continued association with Lemon Tree only underlines the basic issue in Indian private equity: too much money chasing too few companies. But more worrying is that the pace of exits has not matched expectations. “The lack of exits emanates largely from an overdependence on IPOs,” says Banerjee. “PE firms have not focused on trade sales to strategic or financial investors.”

So while Warburg — or for that matter, any large PE firm — reaped multi-bagger returns on picks like Bharti, Kotak Mahindra, Max India and Ambuja Cements, it may be increasingly difficult to replicate that success. There are more failures than successes in PIPE deals and Rajeev Gupta goes so far as to suggest that Indian equities have given zero returns for the past five years and so, therefore, have most PIPE deals.

It will be at least another four years before we know how Warburg’s latest investments play out. Meanwhile, even as decisions will have to be taken on transactions made around 2006, Warburg is clearly looking to spread its risk across industries. The earlier unnamed private equity veteran says, “You can probably call the approach conservative but it is more a strategy to adapt to the changing times.

From what I hear, there is a lot of thinking and reassessment going on with respect to investments in India.” The task will only get tougher as large corporates — including the likes of Tata Capital, Aditya Birla Group, Ajay Piramal and Mahindras — start their own private equity ventures as well. The challenge for Warburg and other PE firms, then, will be to differentiate itself and take on newcomers who understand several industries thanks to their conglomerate experience. It will now need to draw from its reservoir of experience of having invested over $40 billion across 650 companies in 30 countries.

Bharti’s Gupta recalls when his company’s stock tanked by about half from its offer price of Rs.45 in 2002. This was not long after it was listed and Warburg ought to have been worried. Far from it. “They asked us to forget about the share price and concentrate on our business,” Gupta recalls. That advice, as time has shown, stood Bharti and Warburg in good stead. If Warburg now follows its own advice and focuses on what it did best in the past — identifying promising businesses — perhaps the

Midas touch will return.