Transition is the keyword in the script for sustainable development. In the struggle to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, various sectors across borders are seeking alternatives that are less carbon intensive. For the food industry, the promise of a green transition is riding on smart proteins, or alternative proteins, believe optimistic food experts.

Smart proteins, a product category that refers to protein-rich, meat-like alternatives derived from plants or made in the lab using animal cells, have a much lower carbon footprint in comparison to the actual animal meat and are being hailed as a vegetarian or cruelty-free option for people who want to avoid non-vegetarian food because of health, environmental or ethical concerns.

While the concept itself is not very recent—John Harvey Kellogg is credited with popularising vegetarian meat made from peanuts back in 1896—the discussion has gained momentum in recent years, with more players jumping on to the bandwagon of the business of vegetarian meat-like products.

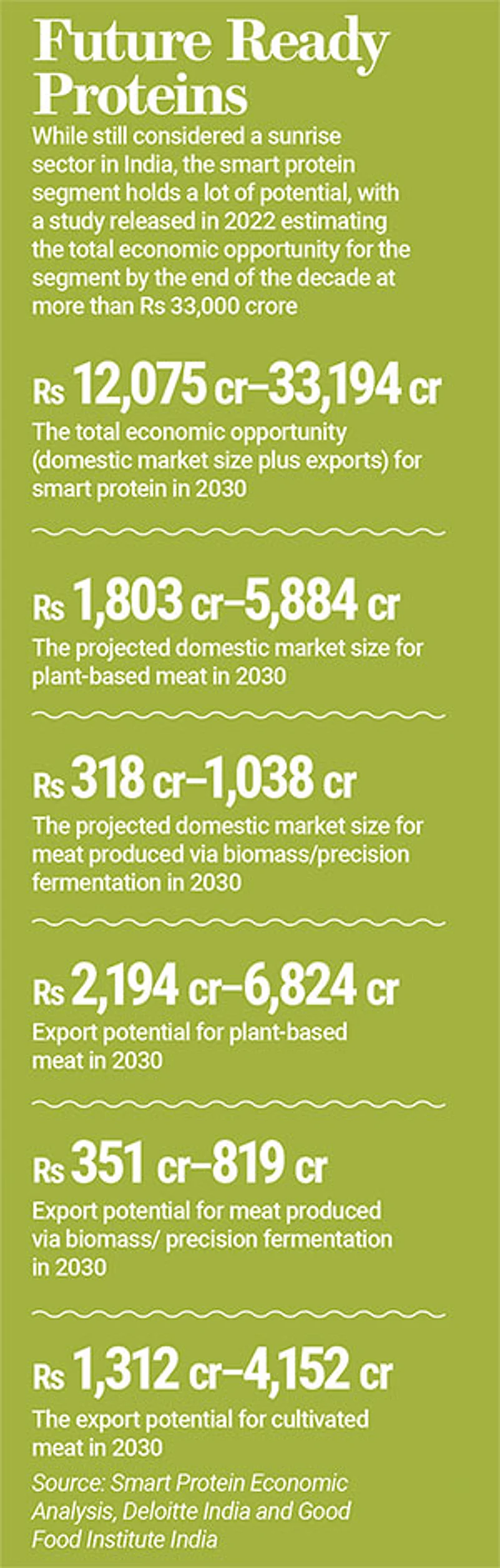

“Globally, 2021 was a banner year for investments in smart protein with $5.1 billion invested into the category, registering an almost 60% increase from 2020, and a 400% increase from 2019—the year Beyond Meat [a producer of plant-based meat substitutes] issued its record-setting IPO,” says Nicole Rocque, senior innovation specialist at Good Food Institute India.

But, when it comes to India, can smart proteins find their place in the sun? Or, will they end up being a product category which is for the “class” and not the “mass”?

A segment that comes quite close when set against common denominators like addressing health and climate concerns on the one hand and affordability and accessibility on the other is the organic food market in the country. While the market for organically grown food is expanding, it is still seen as a niche, largely because of the cost factor but also because of lack of wider availability. Looking at the costs involved in bringing alternative proteins to the retail market as well as their near absence in the offline stores, one wonders if the segment is headed for a fate similar to organic foods that are yet to find wider acceptance among consumers.

The Upside of Being ‘Smart’

Smart protein can serve as a replacement for animal protein available in animal-derived meat, eggs and dairy, thus catering to those who have switched to vegetarian or vegan diet. It usually belongs to one of the, or is a combination of, three categories—cultivated meat, plant-based protein and fermentation-derived protein. Cultivated meat is lab-grown meat made from cell culture. In plant-based protein, biomimicry approach is used to mimic the taste and texture of meat. In fermentation-derived protein, microbial organisms are used to produce plant-based products or cultivated meat.

A report by the Good Food Institute and Ahmedabad-based incubator CIIE.CO, titled Building an Ecosystem for Cultivated Meat in India (2021), says that smart protein offers a platter of benefits ranging from next generation solution in the arena of food security, clean environment and saving resources of nature to addressing climate change, land and water scarcity and public health risks like zoonotic diseases and pandemics.

Global food systems were responsible for one-third of the total greenhouse gas emissions in 2015, according to a study published in online journal Nature Foods. The study, which has also been cited by the World Economic Forum, estimates that 57% of this emission comes from the production of animal-based foods and 29% from plant-based foods.

The other concern that smart protein addresses is animal cruelty as it does not involve animal slaughtering. According to a report by the Boston Consulting Group, a global consulting firm, and Blue Horizon, which invests in agriculture and food processing sector, most consumers of meat want to reduce the amount of animal protein in their diet, especially if they can do so without sacrificing the taste or paying more.

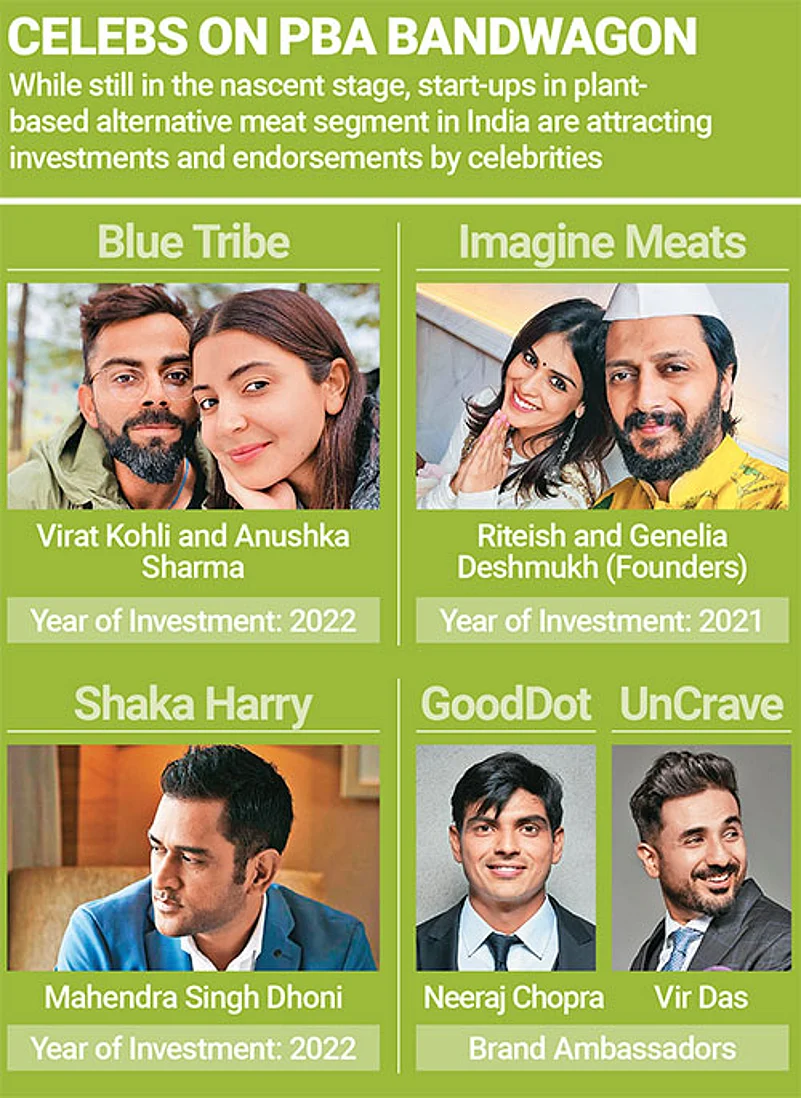

Conscious consumerism has picked up, says Sohil Wazir, chief commercial officer at Blue Tribe Foods, a pioneer in plant-based products supported by actor Anushka Sharma and cricketer Virat Kohli. “There lies a segment among non-vegetarians—that of conscious consumers who care about the effects that their diet and lifestyle have on the planet and the environment. These are the early adopters,” he notes.

The alternative proteins market has spiralled up in just the last two and a half years, says Wazir. “We have seen an increase in the number of people who are now conscious about their decisions, especially the younger generations—the millennials and the Gen Z and Gen Alpha. They are aware that now the health of the planet is in their hands and they are willing to take steps and measures to increase the longevity of the planet,” he observes.

Organic Comparison

In case of India, it is not dietary preferences, but access to the food products, determined primarily by affordability and physical accessibility, that might hold the key to understanding the consumption behaviour.

Organically cultivated food products are generally more expensive than their conventional counterparts, mainly due to the limited supply compared to demand. High labour input and low crop yield have led to high production costs, according to Fortune Business Insights, “The costs are nearly 50% more than conventional food products. The price factor has limited product penetration, especially in developing countries,” it adds.

Juxtapose the situation with that in the smart protein segment. Vegetarian meat is more expensive than animal meat—the price of a 250-gram packet of vegetarian chicken nuggets begins at Rs 300 online. At nearly the same price, one can get a 500-gram packet of regular chicken nuggets.

The Good Food Institute’s 2021 report states that Indian customers are price-sensitive and entrepreneurs will have to “test the waters by extensive customers validation and launching their products at a limited scale before scaling up the production process”. Deep tech investors are not very open to investing their money on cultivated meat start-ups due to the costs related to research and development, infrastructure, long gestation period and slow “market commercialisation”.

Another common factor that affects both smart protein and organic food products is availability. “[T]he most optimistic upside scenario could be constrained by production and distribution capacity. For instance, the scenario assumes that about 120 million tonnes of alternative proteins will be consumed throughout Asia Pacific, where many people, including more than 50% of India’s population, still live in rural areas and are unlikely to find alternative proteins in their local markets,” the report by the BCG and Blue Horizon warns.

Wazir agrees that distribution is one of the major costs for companies as their manufacturing is more centralised. “We also need to ensure that our products are top quality if we want consumers to shift a part of their meat consumption. Hence, ingredient costs go up,” he says.

“I usually purchase … [plant-based meat] online as I do not often find it offline. Normal organic food is more easily available than plant-based protein as there is a lot of organic food stores physically present in most major cities today,” says Nayana Premnath, an influencer on Instagram. She is vegan and has switched to plant-based protein. She says, “While price may vary depending on the product being consumed, the price [of plant-based protein options] is on the higher side.”

This is quite similar to the situation the organic food market had found itself a few years back.

A 2003 report, Market Opportunities and Challenges for Indian Organic Products, by the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture and ACNielsen ORG-MARG cites price and lack of marketing of the product as major reasons for unsold stocks of organic products in the national market. When traders, exporters and producers were asked to assess the profile of potential customers in the domestic market, 90% of them believed that upper class consumers would be interested in buying organic as against 10% indicating upper middle class and none speaking for the lower middle class.

Similarly, the demand for vegetarian meat is expected to come from those who are aware of it and can afford it. “A key to unlocking the affordability of plant-based foods will be to increase the scale of production, eventually achieving economies of scale across the entire value chain. Inconsistencies on the supply side lead to batch-to-batch variability and lower quality production of raw materials by the processor, with low demand from end-product manufacturers,” says Rocque.

There are other challenges as well. Wazir says, “The primary challenge is to help people overcome the mindset that plants—with technology—cannot provide the same taste and feel of meat that they love so much.

Creating a product with almost the same texture, taste and cooking method as a traditional meat item with carefully selected plant-based ingredients is a different ball game altogether.”

Greenwashing a Concern

Ziynet Boz, assistant professor in the department of agricultural and biological engineering, University of Florida, in an article published in the Institute of Food Technologists magazine, writes, “For alternative protein sources to be mainstream, consumer acceptance must be achieved … Since consumers usually do not know the potential health or environmental benefits, the industry may be prone to greenwashing and making unsupported health benefit claims. For this reason, heuristics surrounding the alternative protein space need to be carefully analyzed.”

Boz argues that despite the demonstrated benefits of environmental sustainability, several uncertainties exist around the emissions and added energy requirements associated with novel protein production methods.

The Fresh Food Consumer Survey 2022 by Deloitte notes that, after years of double-digit growth, the sales of plant-based alternative (PBA) meat were stagnating. PBA saw no growth in its consumer base in the US, while there was a drop in positive perceptions related to its consumption—there were fewer people in 2022 who were willing to pay a premium for PBA meat and considered plant-based food healthier and environmentally more sustainable than fresh meat, the report states.

The regulation of the organic food market in India was introduced only in 2018 under the Food Safety and Standards (Organic Foods) Regulation, 2017. It mandates that a product cannot be marketed or sold as organic food unless it complies with all the requirements laid down under the act. However, there is no such regulation in place for the smart protein segment, making greenwashing a real threat there.

The Road Ahead

The BCG-Blue Horizon report states that “every tenth portion of meat, eggs, and dairy eaten around the globe is very likely to be alternative” by 2035. “[A]lternative-protein revenues will reach $290 billion in 2035, with the profits distributed throughout the value chain: to the startups and incumbent food companies producing alternatives, the upstream players providing the industry with the inputs and tools needed to unlock these revenues, and the investors willing to support their efforts,” it adds.

Gautam Godhwani, managing partner at Good Startup, a Singapore-based venture capital firm investing in the alternative protein sector, says, “There continues to be investor excitement about the alternative protein sector in India. Investors will initially engage with start-ups in India that have the potential for global market penetration until the domestic market develops. Indian start-ups have a cost advantage relative to developed markets for production, while the country’s agricultural output provides the potential for novel ingredients.”

Shruti Srivastava, investment director at early-stage venture capital platform Avaana Capital, says, “Among the various kinds of alternative proteins, plant-based proteins are more commercial ready. Investors are recognising the opportunity that this space holds and we are seeing several start-ups come up in this space. India also has an advantage given the availability of a large variety of legumes or plant-based protein sources to serve as feedstock.”

A 2017 report by the Indian Market Research Bureau pegged the number of Indians with protein deficiency at around 80%. The size of the population means the share of those in need of protein-rich diet is high.

Opportunities are set to outweigh challenges in the future. Godhwani says, “We expect that India will become an innovation leader in the alternative protein industry, given its rich talent base and agricultural output. Asia will also be the largest market for the sector over time and consumers will expect products that cater to local tastes and preferences.”

Rocque adds, “With Indian smart protein companies making a conscious shift away from Western formats that were limited to burger patties, nuggets, sausages, etc., towards more Indian flavours and applications in their catalogues, there is potential to fill a growing demand for such formats in international markets, particularly for the Indian diaspora.”

The smart protein segment can make a notable impact on the environment only if it gains wider acceptance, for which it must be seen as a product for the masses. Practically speaking, it may not have some of the advantages that organic farming inherently has and must rely on proper strategy, pricing and policy push to make itself relevant.