Dear Reader,

The Inference | AI Enters The Gym, Inside India’s Consumer AI Paradox, And More

Artificial intelligence is no longer just about breakthroughs in labs or pumping billions of dollars into data centres — it’s in our hospitals, courtrooms, classrooms, and on the battlefield. At Outlook Business, we believe that India needs a sharp, nuanced, and people-first lens on this transformation.

Artificial intelligence is no longer just about breakthroughs in labs or pumping billions of dollars into data centres — it’s in our hospitals, courtrooms, classrooms, and on the battlefield. At Outlook Business, we believe that India needs a sharp, nuanced, and people-first lens on this transformation.

The Inference is our attempt to make sense of a world being rewritten by AI. In this newsletter, we bring you frontline narratives, boardroom insights, and data you can trust. Whether you’re an investor, founder, policymaker, or just curious — this is where the signal cuts through the noise.

In this edition of the newsletter:

AI is entering fitness regimes

Inside India’s consumer AI paradox

Curse of the value chain?

Bad things in small packages

HUMANS IN THE LOOP

AI is entering fitness regimes

Jacked-up, sweaty men with bulging chests and biceps, working out with Phonk music in the background. It is a common visual on millions of mobile screens, with fitness one of the most popular niches on YouTube and Instagram. The niche spans everything from grainy videos of legends like Arnold and Ronnie Coleman to desi influencers like Jeet Selal and Saket Gokhale explaining the basics of bodybuilding.

If trainers were the first wave, watching videos and learning can be called the second wave of fitness. With wider AI use, we are now seeing a third wave in India. The science of diet and training has not changed much. The way people learn has. Fifteen years ago, you had to talk to a trainer to get started. Now tools like ChatGPT and Grok have become quick consultants for the tech-savvy.

Sakshi Singh, a hospitality consultant, began with simple questions on weight loss. It gave generic answers at first. The engagement deepened over the last year. “I wrote down the macros of Indian dishes that I eat frequently, compiled a clean list, and used it to create a custom GPT for daily nutrition tracking,” she explained. The tool combines food data with a workout log and returns a plan that feels personal. What began as a basic query has become a steady habit.

From tracking workouts to logging diets, ChatGPT is showing up in many small ways for fitness-focused users. OpenAI’s recent analysis of user activity was not surprising: nearly 6% of all queries globally were about practical guidance on health, fitness, and self-care. It reflects what people already do in the gym and kitchen — they just want a little structure.

Motivation is still the stumbling block. Tools can advise, but they cannot take you to the gym. Prince Raj, a media executive, found a routine that works for him. He uploaded an English PDF of the Bhagavad Gita into a GPT along with his programme. It gives him a relevant quote before each session. “On days of frustration or lethargy, the nudge is enough to lace up and go,” he says.

Others use AI to stay updated. Abhishek Maheshwari, an entrepreneur, set an alert that compiles early-morning reads from leading health publications. At 8 AM he gets a short brief with pointers he can apply the same day. He likes the filter: it cuts noise and saves time.

Not everyone is convinced. Ravi Yadav, a certified fitness coach in Lucknow, says AI is useful for structure but not for supervision. A tool can suggest exercises and progressions, but it cannot correct form in real time or notice discomfort that a client ignores. He also points to the social side of training. Many people treat the gym as a communal setting — they look for cues, energy, and company. A plan on a screen cannot replace that. He uses AI to draft templates and food lists but insists beginners should learn movement with a coach or experienced partner.

These experiences show a simple pattern. AI can help you start. It can save time on planning and tracking. It can offer ideas and reminders. The hard parts remain human: showing up, lifting well, eating consistently. For many, the best results come from a blend. Use AI to organise the day. Use people for feedback and accountability. If this third wave settles into that balance, tools and trainers can reinforce each other and make fitness easier to stick with.

FROM THE TRENCHES

The consumer AI paradox in India

The AI landscape is evolving rapidly and India is not even a runner-up in the sweepstakes. The reason most widely cited is lack of talent. But that is half the story. “India has no shortage of AI engineers,” says Tanuj Bhojwani, a tech entrepreneur and the former head of People+AI.

Desi engineers design models in Silicon Valley, work at the bleeding edge of global labs, and build creative tools used by millions worldwide. Yet when it comes to consumer-facing AI at home, the shelves are surprisingly bare.

Bhojwani believes the problem is monetisation. “Consumer tech in India has thrived on three models. One is I can get you to gamble. Second, I can hook you and show ads. The third is when the customer pays directly,” he says. AI products do not fit these neatly. Gambling and addiction-driven models are limited by regulation, and direct payment works in high-income markets where people spend freely on subscriptions. Global giants like OpenAI and Google can subsidise their apps. Local startups cannot.

That leaves a thin, affluent base. But the habits of India’s creamy layer mirror those of Western users. “If you are already using ChatGPT or Perplexity, why would you switch to an Indian clone?” Bhojwani asks. At the same time, Indian talent is hardly idle. Startups like Dashtoon and InVideo are built by Indians but aimed squarely at global creators. Glean, which focuses on enterprise-grade AI and search, employs more engineers in India than in the United States. The irony, Bhojwani suggests, is that while Indians are building world-class AI products, few are designed for the Indian consumer.

Investors, too, lean towards safer bets. Bhojwani points to the preference for “baniya businesses” like Swiggy or PhonePe, which scale by labour or regulatory arbitrage.

Consumer AI, by contrast, requires patient capital and experimentation. Even massively funded Indian AI ventures like Sarvam AI and Krutrim carry significant backing from global investors such as Khosla Ventures, Lightspeed, and Matrix Partners. Add to this the structural barriers — low per capita income, a limited paying base, a tax-heavy regulatory mindset, and operational inefficiencies that make scaling harder. Together, these create a market stacked against serious consumer AI.

The sober conclusion is that India’s consumer AI is unlikely to be built for India in the near term. It will be built from India, for the world. The talent is here, the capital is flowing, but the breakout consumer product for the Indian market is still out of reach. “Indians will keep building world-class apps… but not for India. Apps from India, not for India,” Bhojwani said.

NUMBERS SPEAK

Curse of the value chain?

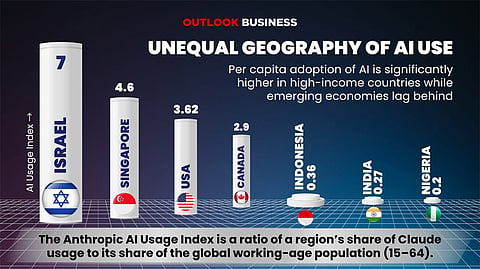

Anthropic’s new AI Usage Index shows that India’s use of Claude.ai stands at just 0.27x per capita of what would be expected based on its working-age population. By contrast, Singapore registers 4.6x and Canada 2.9x. The report also notes that in low-income countries, usage tends to cluster around narrow technical tasks such as coding, while in high-income countries adoption spans a wider range across education, science, and business. In other words, India’s current users are a relatively small, tech-savvy cohort.

But the gap between present and potential is striking. A recent NITI Aayog report projects that broad-based AI adoption could add an additional $1 trillion to India’s economy over baseline projections in the next decade, raising GDP from $6.6 trillion to $8.3 trillion by 2035 under the government’s aspirational path.

Vivek Wadhwa, CEO of Vionix Biosciences, sees a familiar pattern. He notes that India was also slow to embrace the internet and smartphones, yet once conditions aligned, it leapfrogged to become the world’s largest YouTube market and a global model in digital payments through UPI. “India may start late, but once the pieces fall into place, it leaps ahead of the world,” he says.

According to him, India’s real AI gains will not come from competing in capital-intensive model training but from inclusive applications like AI tutors in local languages, real-time farm advisory tools, and low-cost healthcare assistants. If India can scale such solutions, it will not only broaden access but also unlock the additional $1 trillion policymakers believe is within reach.

WORDS OF CAUTION

Bad things in small packages

Microsoft says it stopped a neat little scam last month: a fake file-sharing email that sent itself “from me to me,” hiding real targets in BCC. The attachment looked like a PDF but was an SVG image that can run code. Open it and you hit a CAPTCHA, then likely a bogus sign-in page to steal passwords.

The drawing charts that were invisible, while the real trick hid in plain sight as long strings of business words — “revenue,” “risk,” “shares.” A script converted those words back into instructions to redirect you, fingerprint your browser, and track the session.

BEST OF OUR AI COVERAGE

Dear Sam Altman, Indian Start-Ups Have A Wishlist For You (Read)

India’s Healthcare AI Start-ups Grapple with a Broken Data Ecosystem (Read)

As AI Anxiety Grips Top MBA Campuses, the ‘McKinsey, BCG, Bain’ Dream Flickers (Read)

AI Start-Ups Ride a Wave of ‘Curiosity Revenue’, VCs Rethink What It’s Worth (Read)

What Exactly Is an ‘AI Start-Up’ — and Does India Have 5,000 of Them? (Read)