The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic,” wrote Peter Drucker, the father of modern management. Few companies in India have put that lesson into practice quite like VIP Industries.

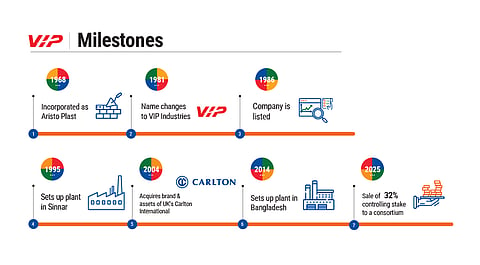

Why VIP Industries’ Promoters Gave Up Control After 50 Years

After five decades at the helm, VIP Industries’ promoters have done what few legacy families dare: ceded control to give the brand a second life

For more than 50 years, the company had come to represent an India on the move. From Aristocrat trolleys on railway platforms to VIP suitcases at airport terminals and Skybags backpacks in college campuses, VIP was ubiquitous.

The Piramal family built, ran and defended the company through economic shifts and market churn for decades. But by 2025, the wheels were starting to wobble. Revenue was slipping. Competition was biting deeper. And there was no clear successor within the family to steady the path.

In July, Dilip Piramal sold a 32% controlling stake to a consortium led by private-equity firm Multiples, retaining about 20% as a minority shareholder. “The younger generation is not interested in management. So, what do I do?” he had said following the announcement.

This wasn’t a sudden unravelling. The company had been wrestling with leadership uncertainty for years. While private-equity offers had come earlier too, some even at better valuations, the family had held on. However, not this time.

“Typically, there is an emotional attachment to a business that has been built, sometimes over generations. It is often intertwined with family identity and legacy,” says Pranav Sayta, partner and national leader, international tax and transaction services, EY India, a consultancy. “That is one of the reasons why Indian promoters have traditionally been reluctant to let go.”

Dilip Piramal is now chairman emeritus, while his daughter Radhika, who was vice-chairperson at the time, has also stepped away.

The Unravelling

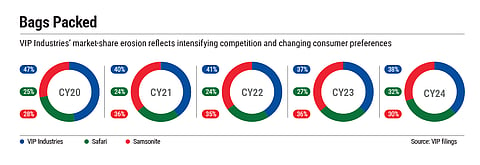

For VIP Industries, Radhika Piramal was the turnaround. When she became managing director (MD) in 2010 at the age of 31, the company was no longer the dominant force it once was. Its market share had slipped from 80% in the 1990s to about 58%.

Although Dilip Piramal had kept the company afloat with professional help, the brand was losing steam. The company had long depended on a professional leadership model, which made it vulnerable when senior executives left.

Earlier departures like Sanjeev Aga in the late 1990s and Sudhir Jatia in 2010 had triggered temporary dips. Radhika brought new energy. She drove a reset built on brand and design. She repositioned VIP for a younger audience, relaunching Skybags with a colourful identity and introducing Caprese, which became one of the company’s strongest growth stories.

Though she helped the business regain momentum, in 2017, Radhika resigned from the post of MD to spend more time in London with her partner. She gradually stepped back from day-to-day operations but stayed involved at the board level. Her move coincided with a pivotal industry shift. Rivals like Safari and digital-first direct-to-customer (D2C) brands were gaining ground through faster launches and sharper positioning.

The gap at the top proved harder to fill than anyone expected. What followed was a revolving door of leadership. Sudip Ghose (2019–21), then Anindya Dutta (2021–23) took over as MD and left in rapid succession.

Financial advisory Ambit Capital noted in March 2024 that churn at the top was straining trade relationships. In 2024, internal cracks widened when board member Nisaba Godrej resigned, citing differences on succession and leadership accountability. Exits at the top had become a pattern. VIP had seen difficult years before. But this time the trouble was continuity. What began as a succession issue had quietly turned structural.

In October 2025, Radhika formally stepped away from the company, ending a 19-year journey.

The Choice Few Make

By 2025, VIP was facing problems it could no longer push aside. It remained India’s largest luggage brand with about 40% of the organised market, but the signs of strain were clear. Warehouses were overflowing with soft luggage even as consumers shifted toward hard luggage. Margins thinned. Discounts deepened. Returns weakened. The company posted losses in all four quarters of 2024–25.

The leadership gaps that had built up over the previous years now caught up with the business. After Dutta’s abrupt resignation as MD in late 2023, chief financial officer Neetu Kashiramka was elevated to the top role. Under her watch, the clean up began. VIP shut unprofitable stores, cut costs and focused on clearing old stock. Kashiramka called 2024–25 “a year of big solves across multiple areas”. Incidentally Kashiramka has also resigned.

The biggest drag was inventory. VIP’s earlier strength in soft luggage had turned into a liability after the pandemic. By the end of 2023–24, VIP carried about ₹900-crore worth of inventory, including ₹300 crore of excess soft luggage. Reducing this pile became central to the revival plan.

The impact was immediate and sharp. Revenue slipped about 3% to ₹2,178.43 crore, and VIP reported ₹69-crore loss for 2024–25, its first in a decade. Analysts, however, did not see panic.

“The company deliberately sacrificed near-term margins for long-term health by addressing excess and obsolete soft-luggage inventory,” says Vinit Bolinjkar of Ventura, a brokerage. “It was a structural clean-up year rather than a fundamental demand slowdown.”

Even as the clean up played out, competition intensified. Safari kept gaining share through quicker design cycles and sharper pricing. Newer D2C brands like Mokobara, Nasher Miles and Assembly tapped into digital-first habits. Luggage had become a style statement for a younger and more aspirational consumer. In comparison, VIP looked slow and staid.

The company has already begun pushing premiumisation to keep pace. It has lined up product launches in the premium and mass-premium brands, expanded Carlton exclusive stores and launched Carlton on platforms like Flipkart and Amazon. VIP also maintained its focus on debt reduction, reiterating its plan to reduce borrowings by ₹130 crore across 2024–25 and 2025–26.

By the first quarter of 2025–26, early signs of stabilisation appeared. Revenue for the June quarter was ₹561 crore, down year on year but up more than 10% sequentially. Losses narrowed from ₹27 crore in fourth quarter of 2024–25 to ₹13 crore in first quarter of 2025–26.

With the stake sale, the shift gathered steam as a fresh board led by Renuka Ramnath and FMCG industry veteran Atul Jain, took control. What began as repair is now a test of execution. VIP is learning to adapt rather than rely on yesterday’s logic.

Letting Go Matters

The cost of holding on too long is visible across corporate India. Jet Airways crumbled under Naresh Goyal’s refusal to restructure. At Fortis Healthcare, the Singh brothers’ governance lapses and unclear succession forced a sale. Kingfisher Airlines collapsed under overreach and a refusal to professionalise.

Against that backdrop, VIP Industries is unusual.

Some legacy firms have modernised without giving up control. Marico professionalised early and built systems that outlast individuals. Emami remains family owned but has transparent succession planning. In VIP Industries’ case, professional management alone was no longer enough.

“With change of ownership, the party has skin in the game…the only goal of PE is to increase the value of the business,” Piramal had said.

Multiples has played this game before. It helped revive Vikram Hospital from financial stress, backed Chola Finance through a strategic shift and supported scale-up at PVR post-acquisition. At VIP, it now brings that playbook to a brand that already has equity but needs sharper execution and stability to regain lost ground.

The Journey Ahead

The new VIP Industries is still in rebuild mode. The focus is on cleaner books, sharper positioning and steadier margins. Analysts expect profitability to improve through 2026–27 as premium products expand and operational efficiencies take hold.

“The new professional management and capital support make VIP structurally stronger. Though it marks the end of an era, this reset is seen as a positive step towards revitalising the company rather than making it more vulnerable,” says Bolinjkar.

Letting go has made VIP lighter in every sense. If the transformation holds, VIP could become a guide for Indian family businesses asking the same question: how to stay relevant without staying in the way.