In Jalgaon—a city of over 6 lakh people in northern Maharashtra, about 388km from Pune and 412km from Mumbai—air travel wasn’t always an option, even though an airport was built there in 1973. For businessmen like Rishab Jain, who runs a company with interests in chemicals, pharma and agriculture, this gap meant relying on slower, less convenient modes of transport.

Regional Airlines Are Flying Again, But Can They Weather the Headwinds?

Regional aviation is experiencing a resurgence thanks to the Udan scheme. However, airlines are likely to face air pockets

“Before air services started, we mostly relied on trains to travel to Pune or other parts of Maharashtra,” says Jain. “It was not only inconvenient for us, but also for clients—especially foreign clients who wanted to visit our manufacturing plants.”

For flyers in smaller cities there is good news. At least three new airlines—Shankh Air, Air Kerala, and Alhind Air—are on the tarmac ready to launch operations this year.

Flying to Far Corners

Bringing connectivity to Tier-II and Tier-III cities has been one of the thrust areas of the Narendra Modi-led government under the Ude Desh Ka Aam Nagrik (Udan) scheme, or Regional Connectivity Scheme (RCS), launched in 2016.

Despite the history of more than half a dozen failed ventures, regional aviation seems to be experiencing a resurgence. A regional airline can operate anywhere in the country; however, it cannot fly between two metro routes.

Shantanu Gangakhedkar, senior consultant and airports lead at Frost & Sullivan, a consultancy, says that India has one of the largest domestic aviation markets globally and as India’s GDP increases so will the passenger demand with India's domestic air passenger traffic expected to be more than 300mn by 2030.

“But the key question is, is the demand constant and is the paying capacity high enough to offer strong profitability to airlines especially for regional airlines. If the load factor is low and if the profit is too thin it makes it very challenging for airlines,” he says.

A few other factors such as ground operations, airport ecosystem and other supporting services are also crucial that need to be available at these smaller airports at a reasonable cost to airlines, he adds.

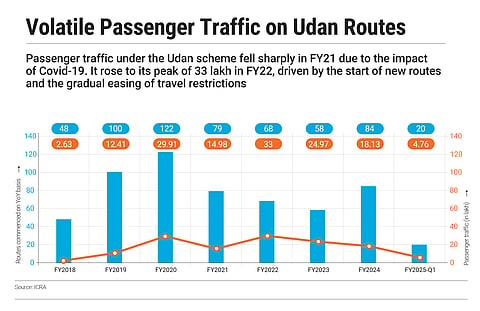

As of 2024, over 1.5 crore people have flown under Udan, and the government plans to connect 4 crore more over the next decade. However, the air passenger traffic under the Udan scheme has been relatively volatile, according to ratings agency Icra. For instance, while traffic grew from 2.63 lakh passengers in 2017–18 to 33 lakh in 2021–22, it declined to 18.13 lakh in 2023–24.

This was largely due to the expiry of three years for the prior period routes commenced and subsequent lower routes awarded in 2022–23 and 2023–24 under the Udan scheme. The scheme provides financial support to airlines for three years from the commencement of a route to bridge the gap between the cost of operations and expected revenues from regional routes.

As of February this year, 323 routes out of 619 are in operation. Disruptions caused by Covid-19, grounding of aircraft due to engine issues, shutting down of airlines and low passenger demand led to 114 routes being discontinued.

One Day I’ll Fly

While passenger traffic on Udan routes posted a CAGR of 8% between 2018–19 and 2023–24, against the industry domestic passenger traffic CAGR of 4%, the penetration of Udan—passenger traffic on Udan routes as percentage of total domestic passenger traffic—has remained subdued at 1–4% between 2017–18 and 2023–24.

As per a September 2024 report by Icra, the low penetration is the result of lower number of routes awarded and operationalised under Udan, its low awareness among the passengers and the inherent limitation that the routes awarded under the scheme are only for a period of three years.

Even though delays in commercialisation of new airports, financial sustainability issues for a few airlines and limited fleet availability have resulted in relatively low penetration, despite these limitations, Udan has created a launchpad for some carriers like Star Air and FLY91, offering them cushion to test routes, understand demand and build a foundation.

Simran Singh Tiwana, chief executive of Star Air, which initially operated helicopters before transitioning into the airline business, says he travelled to some of the remotest parts of India with politicians who would hire helicopters during elections. Locals there, he recalls, often linked their lack of progress to the absence of reliable transport infrastructure.

“That's when we realised the immense potential in regional connectivity. We were uncertain about the paying capacity of people. However, the Udan scheme provided us the leeway to assess spending patterns, as the viability gap funding [VGF] mitigated some operational risks,” he says.

Today, after six years of operations, Star Air flies to 24 destinations with 60–65% of its routes still under Udan.

Considering India's population of 1.4bn, with at least 65% residing in smaller regional towns, and only about 10% of the population flying—3% being unique flyers—there's significant untapped potential, says Tiwana.

Manoj Chacko, managing director and chief executive of Goa-based FLY91, says aviation success hinges on financial discipline. “It’s really about flying between point A and B and ensuring your cost structure stays below your revenue structure,” he says. “The moment you forget the fundamentals, you fail.”

Flying Into Headwinds

Many regional airlines, Chacko believes, went down because of their lack of preparedness. Poor capital planning, inadequate understanding of leasing and maintenance contracts, and a lack of understanding of industry intricacies cost them dearly. “These aren’t optional; they’re pillars,” he says.

Stressing that while people think of aviation as a service industry, it’s transportation, Chacko says, while service matters, it’s not the differentiator. “In aviation, service is hygiene—on-time performance, clean cabins, safety. Airlines spend huge amounts of time and effort in delivering basic hygiene, but aviation is about aircraft utilisation, faster turnarounds and selling every available seat…It’s about how well you can sweat the asset.”

FLY91, which completed a year of operations, operated over 3,500 flights and carried nearly 1.7 lakh passengers in its debut year.

"Before we launched, there was no regular link between Agatti [in Lakshadweep] and Goa or between Jalgaon and Goa or Sindhudurg and Pune,” Chacko says, adding that Fly91 has benefited significantly from the Udan scheme

The airline was awarded 20 sectors under Udan and received VGF that cushioned early-stage operational losses. Today, nearly half of its seat capacity is Udan-supported.

“Udan gives you sustenance money for three years,” he says but cautions that not every subsidy route works. “For every ten sectors we start, six or seven succeed. I think it’s the same with Udan. The only difference is, for the first three years, you can fly 100% of these routes because there’s a subsidy at the end of it. After that, 60–70% may still be viable.”

Experts believe that most regional airlines previously failed because they focused too heavily on subsidies, ignored the fundamentals of aviation and lacked financial and operational discipline.

Experts believe that most regional airlines previously failed because they focused too heavily on subsidies, ignored the fundamentals of aviation and lacked discipline

“They might have shifted focus by going just after the subsidy. But while benefiting from VGF is advantageous, the primary objective should be to develop sectors that eventually become commercially sustainable,” says Tiwana.

With three new airlines looking at entering the Indian regional aviation landscape this year, Chacko says that it is not a new phenomenon and that there has been a constant stream of people trying to get into the small-airline business.

“A lot of people who start these are not necessarily very serious, or they don’t understand the intricacies of regional aviation. It’s more for the glamour or for reasons outside aviation. Some think it’s an easy business to get into. Every year, there’s talk of some small airline starting somewhere in India. We've had Paramount in Coimbatore, Air Costa in Vijayawada, TruJet in Hyderabad, FlyBig out of Guwahati, and Pegasus...," he says.

All Set to Soar

An industry representative, who has worked with a failed regional airline in a senior position, says that regional aviation has a lot of opportunity, and the airlines, including the one he was in, failed largely because of financial mismanagement and administrative issues. Another industry veteran, who didn’t want to be named, says that a lot of companies fail because they don’t have their capital structure and funding sorted.

“What a lot of companies do is that they bid for the Udan routes, and once they get them, they then go to the investors and seek funding,” he says. He adds that a lot of companies announce plans to foray into the market but are unable to follow through if the funding doesn’t happen.

Everyone agrees the demand for regional air travel is real and growing, driven by rising incomes and aspiration in smaller cities.

Frost & Sullivan’s Gangakhedkar says that the market has evolved with the middle class expanding and purchasing power increasing. Technology, too, has aided in reducing operating costs for airlines. Additionally, the number of airports in these smaller cities have also increased now making these regional routes possible.

“Airlines, however, need to approach this with caution as with over competition the demand may spread out and with highly competitive pricing, airlines may struggle to achieve strong profitability,” he adds.

Many regional airlines now function as feeder carriers to larger airlines operating from metro hubs—helping generate demand for themselves while offering last-mile connectivity for travellers.

For Chacko, the only thing that needs to change—and not just for regional but for mainstream aviation—is the Indian banking system’s attitude towards aviation.

“If I want to set up a chemical factory for ₹50 crore, banks will fund it. But if I want to buy an aircraft for ₹100 crore and ask for ₹10 crore funding, I won’t get it. Aircraft are far more liquid assets than a chemical factory. It’s just the mindset of the banking system,” he says.

With airlines like Indigo and Air India investing heavily in their global aviation ambitions, the regional sector may no longer be a sideshow. As full-service carriers focus on international expansion and wide-body routes, regional players have the opportunity to become vital connectors within the country’s vast hinterland. With an improving ecosystem, India’s regional skies might finally be buzzing with big mechanical birds making business people like Jain happy.

“Flights are a lot more convenient,” he says. “More foreign clients are willing to travel, who didn’t earlier want to since they would have to take the train. And so conversion of prospective clients—because they have seen your factory—is much more likely.”