In a span of 45 days, over nine antibiotics across five different classes were administered to a child with bone marrow cancer. As the 15-year-old American patient’s immunity had taken a severe hit due to chemotherapy, a multi-drug-resistant bacteria was threatening his life.

Grit, Gamble and a Giant Drug Discovery: Inside Habil Khorakiwala’s Bold Rebuild of Wockhardt and Indian Pharma

Wockhardt’s pivot to create novel antibiotics is not only stoking its revival, but also heralds a new trajectory up the value chain for India’s pharma sector

Nothing seemed to work.

With few options left, the medical team secured the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) permission to use a novel drug called Zaynich that was still in the investigation stage. After a gruelling few weeks of treatment with the drug, the infection subsided.

Thousands of miles away in Mumbai, 83-year-old Habil Khorakiwala heaved a sigh of relief. His quarter-century of punt on antibiotic research was getting vindicated at long last.

Zaynich, a breakthrough antibiotic, whose clinical trials were completed earlier this year with 96.8% efficacy and is awaiting FDA approval, has already saved 51 lives in emergency cases when most other antibiotics failed.

But it has given more hope to Khorakiwala, the founder of Wockhardt which has discovered the promising drug to fight superbugs, than anyone else. Over two decades, he has bet the farm on discovering new antibiotics while the pharma giants of the West stepped away.

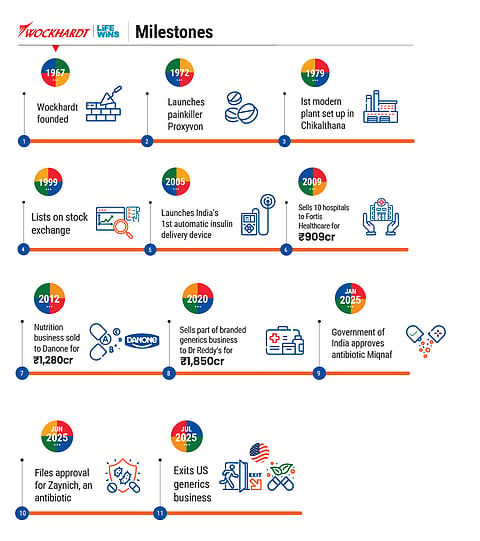

Miqnaf, another antibiotic developed by the company, was launched in India this year after regulatory approvals. When The Lancet published clinical results of Miqnaf in September, it marked the first time an India-origin molecule had found a place in the world’s most-respected medical journal.

At present, Wockhardt boasts a pipeline of six novel drugs against infections.

“Zaynich and Miqnaf show that Indian companies can now create original molecules that meet the highest regulatory and clinical standards. Innovation needs patience and conviction...India needs more entrepreneurs and investors who are willing to think in years, not quarters,” says Vivek Wadhwa, a biotech start-up founder.

Courage Amid Calamity

From the 1990s to the turn of the millennium, Wockhardt was one of the shining stars of India’s pharma ecosystem. It was rapidly growing through big-bang acquisitions in the US and Europe. Legend has it that KV Kamath, who was leading ICICI Bank at the time, had offered Khorakiwala a carte blanche of $300mn to fund his buyouts.

Yet fortunes were quick to turn.

A wily treasury officer in Wockhardt had a penchant for making big bucks off speculative derivatives trading. When the global markets crashed in 2008, those bets soured. And the company was saddled with a giant debt of over ₹4,000 crore.

There was more pain to come. In the following years, the US drug regulator clamped down on Wockhardt’s manufacturing plants. The company’s sales plummeted as a result, while creditors came calling to recover their dues.

But Khorakiwala stuck to his guns. When banks forced him into a restructuring plan and took control of the company’s finances, he fought to keep the R&D efforts alive.

Instead, he sold off several cash cows over the years—some hospitals to Fortis, a nutrition business to Danone, a veterinary pharma unit to Vetoquinol and a portfolio of generics brands to Dr Reddy’s—to keep the lights on in Wockhardt’s labs.

“There are moments in the life of an institution when decisions must be made not for today but for decades to come. Moments that demand courage over comfort, conviction over convention,” says Khorakiwala.

“Wockhardt’s journey over the past few years has been defined by such a moment…we chose to transform, not incrementally, but fundamentally,” he adds.

Economics of Survival

Khorakiwala saw the problem with the state of things in the 1990s. Doctors were already complaining of rising deaths due to anti-microbial resistance (AMR), which meant that microbes were learning to evade old antibiotics. And the situation was only going to worsen. After all, it was evolution at play.

A study published in The Lancet last year estimated that by 2050, AMR could cause 1.91mn deaths directly and be associated with more than 8mn, globally. South Asia and Latin America were projected to have the highest mortality rates.

“I knew ultimately Big Pharma will exit the business in a matter of time. Resistance will increase and new antibiotics will be needed,” Khorakiwala says. “And that is how we took a call to stay in one area and focus on drug discovery.”

When The Lancet published clinical results of Miqnaf in September, it marked the first time an India-origin molecule had found a place in the world’s most-respected medical journal

The discovery of penicillin in 1928 was a pivotal moment in human history. For the first time, a scratch from a rose bush, a difficult childbirth or a contaminated surgical instrument no longer carried the same mortal risk. As demand for antibiotics shot up during World War II, it paved the way for the emergence of Big Pharma companies like Pfizer, Merck and Eli Lilly. But they soon realised that fighting microbes wasn’t lucrative enough and stopped innovating.

According to the World Economic Forum, 26 classes of antibiotics had been discovered by 1962; since then, only seven new classes have been found and only one since 1987.

For Big Pharma, the problem was that doctors prescribed antibiotics only for short periods, whereas ailments like diabetes, hypertension and cancer needed lifelong medication.

“There’s also a hierarchy in prescribing: doctors reserve the most potent antibiotics for the most severe cases. As you develop stronger antibiotics, the target population becomes smaller,” says Vishal Manchanda, a pharma-sector analyst at brokerage firm Systematix.

“Meanwhile, large global innovators look for drugs with billion-dollar annual sales potential. Today, the highest-selling antibiotic globally is Zavicefta, at about $700–750mn. That’s far below what Big Pharma wants,” he adds.

That is why they have largely turned to more financially attractive therapeutic areas. For instance, Merck spent more than $46bn on the R&D of its cancer drug Keytruda, which brings in annual sales of nearly $30bn. It’s not that companies are plain greedy, costs of development are significantly higher in the West. According to industry estimates, it costs around $1.5–2bn to launch a new drug in the US.

Meanwhile, Khorakiwala estimates that Wockhardt has spent about $700-800mn on its antibiotic portfolio of six drugs. On an average, that’s less than one-tenth the money that Big Pharma spends.

“We have another budget of about a few hundred million dollars over the next several years. But at the same time, the same thing you expect from global R&D companies, they would have spent between $10bn and $15bn…you get an idea of how we do it frugally in India,” he says.

Inside the Lab

It was around the time Wockhardt was dealing with the fallout of the derivatives-trading crisis.

Mahesh Patel, Wockhardt’s chief scientific officer who was nearing retirement, met Khorakiwala with an impassioned plea. The research programme he was working on was showing early signs of success. So, he was ready to carry on working even without a salary.

Of course, the boss gave him an extension. The project Patel was working on was Zaynich.

Khorakiwala stayed close to his team of 150–200 scientists even when the odds looked impossible. He often sat through long technical review sessions, which were sometimes three-day marathons, listening to researchers and collaborators across 15 scientific disciplines as they dissected data and setbacks.

That is why he had enough insight to stay the course through years of uncertainty. “To build up a reasonable expertise in anti-infective research took us nearly 8–10 years,” Khorakiwala recalls.

By the time the company achieved the complete spectrum of competencies required for new-drug discovery, nearly 18 years had passed.

Wockhardt’s scientific success also needs to be seen from the lens of its environment. Although its R&D expenditure levels have remained at 4–6% of revenue which is the same for the Indian pharma sector at large, its peers were hardly trying to discover novel drugs.

“Most of Indian pharma R&D goes into patenting tweaks of generics and making biosimilars. That is different from patenting a new molecule. Very little goes into genuinely new chemical entities,” says Manchanda.

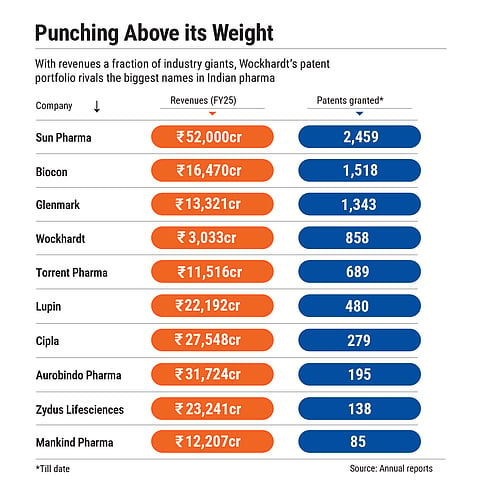

In spite of its financial troubles, Wockhardt has filed 3,285 patents worldwide and has been granted 858. It is the fourth-highest patent holder in the Indian pharma industry, although it does not feature among India’s top-25 pharma companies by revenue and has recorded net losses in the last eight of nine years.

Eye on the Future

“I think people don’t understand the gravity of what you, your scientists, your entire team have created...[it] is the true odyssey of courage,” Hansal Thakkar, a Wockhardt shareholder, said at a meeting with Khorakiwala and the company’s management earlier this year.

The company’s stock price, which has jumped more than 5x in the past couple of years on the early signs of successes of its portfolio, reflects the sentiment. In the same period, the broader Nifty Pharma index has returned just 44%. Last year, it raised ₹1,000 crore in a private placement from funds managed by veteran investors like Madhusudan Kela and Prashant Jain.

Everyone is placing a bet on what the promise that the company holds in the future, says Khorakiwala. Even though generics still contribute the bulk of its revenues.

“The company has had its fair share of downturns, but Zaynich has come into the picture and when you see the revenues coming from this drug, it will be a turnaround for the company,” says Nirali Shah, Analyst, Institutional Research at Ashika Group.

According to estimates, Zaynich has an addressable market of $7bn in the US and Europe. Meanwhile, Miqnaf’s addressable opportunity globally is pegged at $3–4bn annually. Not everybody is so sure. For one, Manchanda of Systematix points out that over the past decade, around 15 antibiotics have received approval from the FDA. Several of those companies went bankrupt as they couldn’t find strong commercial footing.

But Leela Maitreyi, director at biotech start-up Bugworks, argues that the market failure of antibiotics is a Western narrative that doesn’t apply to India and the rest of the developing world where the incidence of AMR is the highest.

Dose of Hope

Even if Zaynich captures 2% of its addressable market, its cost will be recouped within a couple of years. “It is the talk of the town, globally. Wherever we go, people are like, ‘Wow, Wockhardt is coming up with this’. The fact that people are talking about India from an innovation perspective itself is a great precedent for us,” says Maitreyi, whose lead antibiotic candidate is going through phase-1 clinical trials in Australia.

Many like her in India’s biotech ecosystem are eagerly waiting for Zaynich’s launch to see how the market reacts. It could either inject courage into India’s pharma industry to go all-in on innovation, or scare it enough to stay cocooned in copycat drugs.

Yet, the stakes are highest for patients like the American teenager. For them it is a matter of life and death.