Earlier this year, Physicswallah (PW) found itself at the centre of a storm. Rumours began circulating that the company was planning to hike course fees five-fold, to ₹20,000. Outrage erupted across social media. Students accused the platform they trusted of betrayal. Rivals fanned the frenzy.

From a Missed IIT Dream to an Industry’s Downfall, the Forces That Pushed Alakh Pandey to Create India’s First Listed Edtech Firm

While edtech has become a graveyard of start-ups, Physicswallah is the sector’s first unicorn to go public. It is also the sole growing company among the top test-prep shops

Alakh Pandey, founder of PW, knew exactly what was at stake. He rushed to Kota, India’s coaching capital, to face his students directly. On stage, before hundreds of anxious teenagers, he punched a hoarding plastered with news clippings of the alleged hike.

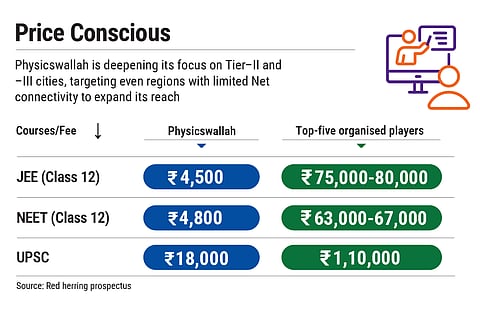

“All of PW’s batches will continue to remain priced under ₹5,000,” he thundered. “If the prices cross ₹5,000, either PW won’t exist, or I won’t be part of PW," he said to the crowd.

The crowd roared.

The inflection point for edtech came when Covid struck. With no choice but to enrol their kids in online courses, many parents were easily convinced to shell out large amounts of money for subscriptions. Prices went as high as ₹1.5-2 lakh.

Highly funded edtech start-ups like Byju’s, Unacademy, Vedantu and WhiteHat Junior pushed this temporary compulsion of lockdowns to the extreme. They sold expensive courses on Fomo. As subscription numbers skyrocketed, venture capitalists (VCs) rewarded them with big jumps in valuation.

This model came crashing down once schools reopened.

According to Traxcn, a data platform, as many as 2,148 start-ups in the sector have shut shop in the past five years. Giants like Byju’s and Unacademy have faded away.

Meanwhile, PW has recently become India’s first publicly listed edtech unicorn.

“They kept course prices low, and because they had a large number of students per teacher, their cost structure stayed lean. This affordability is what made them stand out,” says Ravi Handa, an edtech entrepreneur whose start-up was acquired by Unacademy a few years ago.

The winning formula for the company to ratchet up its paying users to 4.5mn has been its ability to control pricing even in its offline coaching centres. While the share of offline coaching revenue became almost equal to online in 2024–25, the average revenue per paying student was ₹6,472.

It is not a coincidence that the number is astonishingly close to the country’s average household spend on tuition.

Not Just Dhanda

After dropping out of college in 2014 and returning to his hometown Prayagraj, Pandey joined a coaching institute for a monthly salary of ₹5,000. In his free time, he would make videos on physics and upload them to YouTube so that his students could refer to them at their convenience.

As Covid shut down classrooms, his YouTube channel went viral. Millions of students across the country discovered him. And an edtech unicorn reached out offering him ₹75 crore to teach exclusively on its platform and acquire PW. But Pandey turned down the offer.

In his school days, Pandey wanted to crack IIT JEE but was not able to afford the high fees of elite coaching shops. He didn’t want to erect a paywall so high that would cut off students like him. “My philosophy was clear from the start: if a trade off has to be made between money and students, money will take the backseat,” he said in a podcast earlier.

“When I started meeting people in edtech, I realised everyone was always talking about sales and revenue. Nobody was interested in the ‘education’ or ‘tech’ of edtech. It became just a dhanda…People don’t understand that if you create a product that actually serves students, the revenue will take care of itself,” he said in a podcast.

Pandey has proved his hypothesis right. In hindsight, the writing was on the wall. When other sectors like movie tickets or retail went online, consumers paid for convenience. But that was not the case in education. Edtechs needed to sell access to those who were left out—and do it in a financially sustainable manner.

Cost of Doing Business

The biggest reason PW has managed to keep its course fees affordable is its exceptionally low customer-acquisition cost (CAC), a rarity in the edtech sector. This efficiency stemmed from its creator-led marketing model centred around Pandey’s YouTube channel, which became the foundation of the brand.

The channel that boasts of over 13.9mn subscribers, laid the groundwork for PW’s success before the platform officially launched during the pandemic. Many in the industry say this played a key role in creating a captive audience for the company from the ground up and hence kept its marketing costs low.

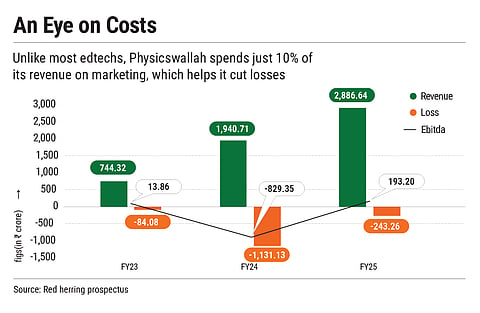

For a few years, the edtech sector witnessed an unprecedented marketing frenzy. Byju’s and Unacademy for instance, spent lavishly on endorsements. The result was a surge in marketing expenditure across the board. Byju’s advertising costs jumped from ₹899 crore in 2019–20 to ₹2,250 crore in 2020–21, while Unacademy’s spend rose from ₹113.4 crore to ₹411.2 crore in the same period.

In contrast, PW’s marketing outlay stood at a modest ₹14 lakh in 2020–21 which was also its first year of operations.

“In online education customer acquisition costs are high. PW managed to avoid that trap by building a brand pull rather than relying on push marketing. By keeping prices affordable and focusing on good teaching, they’ve built loyalty without overspending,” says Yagnesh Sanghrajka, founder of early-stage investor 247VC.

Another reason behind PW’s sustainable growth has been its disciplined, value-driven acquisition strategy, in sharp contrast to the acquisition sprees of Byju’s and Unacademy.

PW’s inorganic growth has been marked by the selective purchase of small, profitable companies that were strong in specific geographies and education verticals.

Instead of overpaying or chasing scale, PW structured its deals in performance-linked phases, ensuring that sellers earned more only if the businesses continued to perform well. All of PW’s acquisitions—iNeuron, PrepOnline and Utkarsh— were structured to strategically expand the company’s presence across categories and regions, without adding long-term debt to its balance sheet.

The contrast with Byju’s and Unacademy could not be sharper. Between 2017 and 2021, Byju’s went on an aggressive acquisition spree (17 companies in five years), which eventually fuelled its mounting losses. Subsidiaries such as WhiteHat Jr and Osmo alone accounted for about ₹3,800 crore, nearly 45% of Byju’s 2021–22 loss of ₹8,245 crore.

Unacademy followed a similar trajectory, acquiring 12 edtech start-ups between March 2020 and December 2021 at a cumulative spend of over ₹500 crore. Many of these ventures (including Mastree and Swiflearn) were shut down soon after. In hindsight, co-founder Gaurav Munjal admitted that several of these acquisitions were driven less by strategy and more by Fomo.

“Byju’s grew too fast and played the valuation game. They focused on fundraising and optics rather than building a profitable, sustainable business,” says Sanjeev Bikhchandani, founder of tech company Info Edge and one of India’s leading start-up investors. “PW, on the other hand, kept its focus on profitability and growth.”

The Coming Disruption

Within a span of five years, PW has become the second-largest test-preparation company in the country in terms of revenue. It is now just a whisker away from toppling market leader Allen which recorded a revenue of ₹3,067 crore in 2024–25, compared to the ₹2,887 crore collected by PW.

More importantly, PW is the only growing company among the biggest test-prep players—Allen, Akash (now owned by Manipal) and Unacademy saw their revenues shrink in 2024–25 amid a rise in AI-led learning, whereas PW grew by 49%.

But this gravity-defying growth has come at the cost of profitability. When the company logged a ₹98-crore profit in just the second year of its operations in 2021–22, it created waves in the edtech sector. VCs lined up outside its doors. Yet, as the Noida-headquartered edtech raised private funding to enter the unicorn club and expand by opening new brick-and-mortar coaching centres and via acquisitions, it slipped into the red in 2022–23.

“The rumours that surfaced about its fee hikes were in part because of its ₹1,100-crore loss last year [2023–24]. It scared the teachers and students. But it has done well to bring the losses under control just before the IPO [Rs 243 crore in 2024–25],” says an industry executive.

“Prateek [Maheshwari, co-founder of PW] is one of the most-shrewd operators out there. If there’s one person who can run a profitable business while growing in the current environment, it is him. But it will only become more challenging as AI assumes a bigger role,” he adds.

The warning signs of AI in edtech are already visible. For example, Chegg, a US-based edtech major once valued in billions, has seen a sharp decline in users and revenue following the rise of generative AI tools like ChatGPT.

“It’s just a matter of time before these tuition classes die out. AI will be one of the biggest reasons,” warns Aniruddha Malpani, a VC who has been a longtime critic of the edtech sector in India.

Is PW alive to the signs? The company says it is integrating AI into its learning ecosystem through an in-house AI model for doubt-solving. It also claims that about 80% of student queries are now handled via AI.

But detractors say these efforts aren’t serious and point to the fact that the company’s spend on technology still remains under 0.5% of revenue.

While PW has brought the ‘education’ back into edtech, can it now do the same with ‘tech’? Students, parents and investors are holding their breath.